On the missionary work carried out during the 16th century in Mexico there is, as we all know, a vast bibliography. However, this huge collection, despite the high level of scholarship and genuine evangelical inspiration that characterize most of the works, suffers from a limitation that would hardly have been possible to avoid: they are written by the missionaries themselves.

In vain would we seek in them the version of the millions of Mexican natives who were the object of this gigantic campaign of Christianization. Hence, any reconstruction of the “spiritual reconquest”, based on the available sources, will always be a partial account, including this sketch. How did the first generations of missionaries view their own performance? What were the motives that according to them inspired and guided them? The answer is found in the treaties and opinions that they wrote throughout the 16th century and throughout the territory of the current Mexican Republic. From them, several valuable interpretive studies have been made in the 20th century, among which the works of Robert Ricard (first edition in 1947), Pedro Borges (1960), Lino Gómez Canedo (1972), José María Kobayashi (1974) stand out. ), Daniel Ulloa (1977) and Christien Duvergier (1993).

Thanks to this abundant literature, figures such as Pedro de Gante, Bernardino de Sahagún, Bartolomé de Las Casas, Motolinía, Vasco de Quiroga and others, are not unknown to the majority of read Mexicans. For this reason, I made the decision to present two of the many characters whose life and work were left in the shadows, but are worth being rescued from oblivion: the Augustinian friar Guillermo de Santa María and the Dominican friar Pedro Lorenzo de la Nada. However, before talking about them, it is convenient to summarize the main axes of that very peculiar enterprise that was evangelization in the 16th century.

A first point on which all the missionaries were in agreement was the need to “… uproot the grove of vices before planting the trees of virtues…”, as a Dominican catechism said. Any custom that did not reconcile with Christianity was considered the enemy of the faith and, therefore, subject to being destroyed. The extirpation was characterized by its rigidity and its public staging. Perhaps the most famous case was the solemn ceremony orchestrated by Bishop Diego de Landa, in Maní Yucatán, on July 12, 1562. There, a large number of those guilty of the crime of "idolatry" were severely punished and a number still very much. largest of sacred objects and ancient codices thrown into the fire of an immense bonfire.

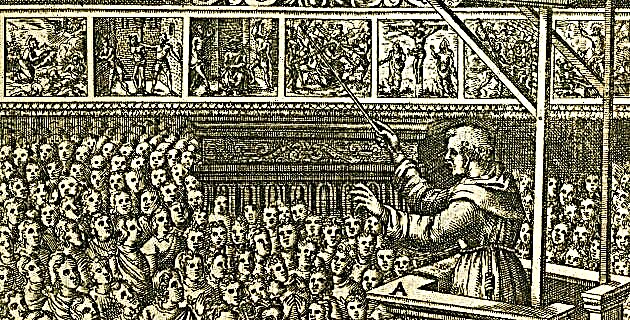

Once that first phase of cultural “slash-grave-burn” was finished, came the instruction of the indigenous people in the Christian faith and the Spanish-style congregation, the only way of life considered by the conquerors as civilized. It was a set of strategies that a Jesuit missionary from Baja California would later define as "art of the arts." It had several steps, beginning with the "reduction to town" of the natives used to living dispersed. The indoctrination itself was carried out from a mystical vision that identified the missionaries with the apostles and the indigenous congregation with the early Christian community. Because many adults were reluctant to convert, the instruction focused on children and young people, as they were like “clean slate and soft wax” on which their teachers could easily print Christian ideals.

It should not be forgotten that evangelization was not limited to the strictly religious, but encompassed all levels of life. It was a true civilizing work that had as centers of learning the atriums of the churches, for all, and the convent schools, for carefully selected youth groups. No artisan or artistic manifestation was alien to this gigantic campaign of instruction: letters, music, singing, theater, painting, sculpture, architecture, agriculture, urbanization, social organization, commerce, and so on. The result was a cultural transformation that has no equal in the history of humanity, due to the depth it reached and the short time it took.

It is worth highlighting the fact that it was a missionary church, that is, not yet solidly installed and identified with the colonial system. The friars had not yet become village priests and administrators of rich estates. These were still times of great mobility, both spiritually and physically. It was the time of the first Mexican council in which slavery, forced labor, the encomienda, the dirty war against the Indians called barbarians and other burning problems of the moment were questioned. It is in the social and cultural sphere previously described where the performance of the friars of singular stature is situated, the first Augustinian, the other Dominican: Fray Guillermo de Santa María and Fray Pedro Lorenzo de la Nada, whose curricula vitae we present.

FRIAR GUILLERMO DE SANTA MARÍA, O.S.A.

Born in Talavera de la Reina, province of Toledo, Fray Guillermo had an extremely restless temperament. He probably studied at the University of Salamanca, before or after taking the Augustinian habit under the name of Fray Francisco Asaldo. He fled from his convent to embark for New Spain, where he must have already been in 1541, since he participated in the Jalisco war. In that year he took up the habit again, now under the name Guillermo de Talavera. In the words of a chronicler of his order “not content with having come from Spain a fugitive, he also made another escape from this province, returning to Spain, but since God had determined the good whereabouts of his servant, he brought him a second time to this kingdom to May he achieve the happy end he had ”.

In fact, back in Mexico, around the year 1547, he changed his name once more, now calling himself Fray Guillermo de Santa María. He also turned his life around: from a restless and aimless sway he made the definitive step to a ministry of more than twenty years dedicated to the conversion of the Chichimeca Indians, from the war frontier that was then the north of the province of Michoacán . Residing in the Huango convent, he founded, in 1555, the town of Pénjamo, where he applied for the first time what would be his missionary strategy: to form mixed settlements of peaceful Tarascans and rebellious Chichimecas. He repeated the same scheme when founding the town of San Francisco in the valley of the same name, not far from the town of San Felipe, his new residence after Huango. In 1580 he moved away from the Chichimeca border, when he was named prior of the Zirosto convent in Michoacán. There he probably died in 1585, in time not to witness the failure of his work of pacification due to the return of the semi-reduced Chichimecas to the insubordinate life they previously led.

Fray Guillermo is especially remembered for a treatise written in 1574 on the problem of the legitimacy of the war that the colonial government was waging against the Chichimecas. The esteem he had for the insubordinate led Fray Guillermo to include in his writing several pages dedicated to “their customs and way of life so that, if we know better, they can see and understand the justice of the war that has been and is being done against them. ”, As he says in the first paragraph of his work. Indeed, our Augustinian friar agreed in principle with the Spanish offensive against the barbarian Indians, but not with the way in which it was carried out, since it was very close to what we now know as "a dirty war ”.

Here is, as the end of this brief presentation, the description he made of the total lack of ethics that characterized the behavior of the Spanish in their dealings with the rebellious Indians of the north: “breaking the promise of peace and forgiveness that has been given to them word of mouth and that they have been promised in writing, violating the immunity of ambassadors who come in peace, or ambushing them, putting the Christian religion as bait and telling them to gather in towns to live quietly and there captivate them, or ask them to give them people and help against other Indians and giving themselves to apprehend those who come to help and make them slaves, all of which they have done against the Chichimecas ”.

FRIAR PEDRO LORENZO DE LA NADA, O. P.

During the same years, but at the opposite end of New Spain, in the confines of Tabasco and Chiapas, another missionary was also dedicated to making reductions with insubordinate Indians on a war frontier. Fray Pedro Lorenzo, calling himself Out of Nothing, had arrived from Spain around 1560 by way of Guatemala. After a brief stay in the convent of Ciudad Real (the current San Cristóbal de Las Casas), he worked with some of his companions in the province of Los Zendales, a region bordering the Lacandon jungle, which was then the territory of several insubordinate Mayan nations. Chol and Tzeltal speaking. He soon showed signs of being an exceptional missionary. In addition to being an excellent preacher and an unusual "language" (he mastered at least four Mayan languages), he showed a particular talent as an architect of reductions. Yajalón, Ocosingo, Bachajón, Tila, Tumbala and Palenque owe their foundation to him or, at least, what is considered their definitive structuring.

Just as restless as his colleague Fray Guillermo, he went in search of the rebellious Indians of El Petén Guatemala and El Lacandón Chiapaneco, in order to convince them to exchange their independence for a peaceful life in a colonial town. It was successful with the Pochutlas, the original inhabitants of the Ocosingo Valley, but it failed due to the intransigence of the Lacandones and the remoteness of the Itza settlements. For unknown reasons he escaped from the Ciudad Real convent and disappeared into the jungle on his way to Tabasco. It is possible that his decision had to do with the agreement that the provincial chapter of the Dominicans made in Cobán, in the year 1558, in favor of a military intervention against the Lacandones who had murdered several friars a short time before. From that moment, Fray Pedro was considered by his religious brothers as "alien to their religion" and his name stopped appearing in the chronicles of the order.

Wanted by the courts of the Holy Inquisition and the Audiencia of Guatemala alike, but protected by the Zendale and El Lacandón Indians, Fray Pedro made the town of Palenque his center of pastoral operation. He managed to convince Diego de Landa, bishop of Yucatán, of his good intentions and thanks to this Franciscan support, he was able to continue his evangelization work, now in the Tabasco provinces of Los Ríos and Los Zahuatanes, belonging to the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of Yucatán. There she again had serious problems, this time with the civil authority, for her determined defense of indigenous women against forced labor on the Spanish farms. His outrage reached the point of excommunicating the guilty and demanding their exemplary punishment from the Inquisition, the same institution that had persecuted him a few years earlier.

Such was the admiration of the Tzeltal, Chole and Chontal Indians for him that after his death in 1580 they began to venerate him as a saint. At the end of the 18th century, the parish priest of the town of Yajalón collected the oral tradition that was circulating about Fray Pedro Lorenzo and composed five poems that celebrate the miracles attributed to him: having made a spring spring from a rock, hitting it with his staff ; having celebrated mass in three different places at the same time; having transformed ill-gotten coins into drops of blood in the hands of a tyrant judge; etc. When in 1840, the American explorer John Lloyd Stephens visited Palenque, he learned that the Indians of that town continued to venerate the memory of the Holy Father and still kept his dress as a sacred relic. He tried to see it, but due to the distrust of the Indians, "I could not get them to teach it to me," he wrote a year later in his famous book Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatan.

Guillermo de Santa María and Pedro Lorenzo de la Nada are two Spanish missionaries who dedicated the best of their lives to the evangelization of the insubordinate Indians who lived on the war frontier that by the years 1560-1580 limited the space colonized by the Spanish. north and south. They also tried to give them what other missionaries had offered to the native population of the Mexican highlands and what Vasco de Quiroga called "the alms of fire and bread." The memory of his delivery is worthy of being rescued for the Mexicans of the 20th century. So be it.