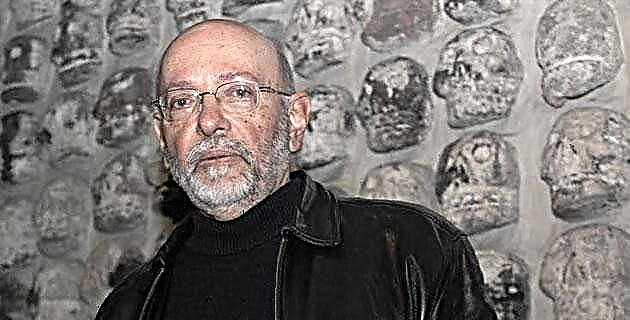

490 years after the Conquest, get to know the vision of the great Tenochtitlan that one of its most renowned researchers has, Prof. We present it to you in an exclusive interview from our archive!

Undoubtedly one of the most fascinating aspects of the pre-Hispanic world is the organization that reached cities as important as Mexico-Tenochtitlan. Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, distinguished archaeologist and recognized specialist in the field, gives us an interesting insight into the indigenous past of Mexico City.

Unknown Mexico. What would be the most important thing for you if you had to refer to the indigenous origin of Mexico City?

Eduardo Matos. The first thing that must be taken into consideration is the existence, in the space that the city occupies today, of a good number of pre-Hispanic cities that correspond to different times. The circular pyramid of Cuicuilco is still there, part of a city that surely had a different form of organization. Later at the time of the conquest, it would be necessary to mention Tacuba, Ixtapalapa, Xochimilco, Tlatelolco and Tenochtitlan, among others.

M.D. What about the forms of government that worked, both for the ancient city and for the empire?

E.M. Even though the forms of government were very heterogeneous at that time, we know that in Tenochtitlan there was a supreme command, the tlatoani, who presided over the government of the city and was at the same time the head of the empire. The Nahuatl voice tlatoa means the one who speaks, the one who has the power of speech, the one who has the command.

M.D. Could we then suppose that the tlatoani functioned permanently to serve the city, its inhabitants, and attend to all the problems that occurred around it?

E.M. The tlatoani had advice, but the final word was always his. It is interesting, for example, to observe that the tlatoani is the one who orders the water supply to the city.

Following his orders, in each calpulli they organized to collaborate in public works; men led by bosses repaired the roads or carried out works such as the aqueduct. The same thing happened with the war: for the Mexican military expansion large contingents of warriors were required. In the schools, the calmecac or the tepozcalli, men received instruction and were trained as warriors, and that was how the calpulli could contribute men to the expansionist enterprise of the empire.

On the other hand, the tribute that was imposed on the conquered peoples was brought to Tenochtitlan. The tlatoani allocated part of this tribute to the population in case of floods or famines.

M.D. Is it to be supposed that the task of administering the city and the empire required government formulas such as those that work in some indigenous communities to this day?

E.M. There were people who were in charge of the administration, and there was also the head of each calpulli. When they conquered a territory they imposed a calpixque in charge of collecting the tribute in that region and the corresponding shipment to Tenochtitlan.

Communal work was regulated by the calpulli, by its ruler, but the tlatoani is the figure that will be constantly present. Let us remember that the tlatoani brings together two fundamental aspects: the warrior character and the religious investiture; on the one hand it is in charge of the essential aspect for the empire, the military expansion and the tribute, and on the other of the matters of a religious nature.

M.D. I understand that the big decisions were made by the tlatoani, but what about everyday matters?

E.M. To answer this question, I think it is worth remembering an interesting point: Tenochtitlan being a lake city, the first means of communication were canoes, that was the means with which merchandise and people were transported; the transfer from Tenochtitlan to the riverside cities or vice versa formed a whole system, a whole network of services, there was a fairly well established order, Tenochtitlan was also a very clean city.

M.D. It is assumed that a population like that of Tenochtitlan produced a good amount of waste, what did they do with it?

E.M. Perhaps with them they gained space from the lake ... but I am speculating, in reality it is not known how they solved the problem of a city of around 200 thousand inhabitants, in addition to riverside cities such as Tacuba, Ixtapalapa, Tepeyaca, etc.

M.D. How do you explain the organization that existed in the Tlatelolco market, the place par excellence for the distribution of products?

E.M. In Tlatelolco a group of judges worked, who were in charge of resolving the differences during the exchange.

M.D. How many years did it take for the Colony to impose, in addition to the ideological model, the new architectural image that made the indigenous face of the city disappear almost entirely?

E.M. That is something very difficult to pin down, because it was really a struggle in which the indigenous were considered pagan; their temples and religious customs were considered the work of the devil. The entire Spanish ideological apparatus represented by the Church will be in charge of this task after the military triumph, when the ideological struggle takes place. Resistance on the part of the indigenous is manifested in several things, for example in the sculptures of the god Tlaltecutli, which are gods that were engraved in stone and placed face down because he was the Lord of the Earth and that was his position in the pre-Hispanic world. . At the time of the Spanish conquest, the indigenous had to destroy their own temples and select the stones to begin the construction of the colonial houses and convents; Then he chooses the Tlaltecutli to serve as the base for the colonial columns and begins to carve the column above, but protecting the god below. I have described on other occasions a daily scene: the builder or the friar is passing by: "hey, you have one of your monsters there." "Don't worry, your mercy will go upside down." "Ah, well, that's how it had to go." Then he was the god that lent himself the most to be preserved. During the excavations in the Templo Mayor and even earlier, we found several colonial columns that had an object at the base, and it was usually the god Tlaltecutli.

We know that the native refused to enter the church since he was used to the large squares. The Spanish friars then ordered the construction of large courtyards and chapels in order to convince the believer to finally enter the church.

M.D. Could one speak of indigenous neighborhoods or the colonial city was growing in a disorderly way over the old city?

E.M. Well, of course the city, both Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco, its twin city, were deeply affected at the time of the conquest, practically destroyed, above all, the religious monuments. We only find the footprint of the Templo Mayor from the last period, that is, they destroyed it to its foundations and distributed the property among the Spanish captains.

It is in religious architecture that a fundamental change occurred first. This occurs when Cortés determines that the city must continue here, in Tenochtitlan, and that it is here where the Spanish city rises; Tlatelolco, in a way, was reborn for a time as an indigenous population bordering colonial Tenochtitlan. Little by little the forms, the Spanish characteristics, began to impose themselves, without forgetting the indigenous hand, whose presence was very important in all the architectural manifestations of that time.

M.D. Although we know that the rich indigenous cultural world is immersed in the cultural features of the country, and all that this means for the identity, for the formation of the Mexican nation, I would like to ask you where we could identify, in addition to the Templo-Mayor, what still preserves signs of the old city of Tenochtitlan?

E.M. I believe that there are elements that have emerged; on some occasion I said that the old gods refused to die and that they began to leave, as is the case of the Templo Mayor and Tlatelolco, but I believe that there is a place where you can clearly see the "use" of pre-Hispanic sculptures and elements, which is precisely the building of the Counts of Calimaya, which is today the Museum of Mexico City, on Calle de Pino Suárez. There you can clearly see the snake and also, still at the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, sculptures were seen here and there. Don Antonio de León y Gama tells us, in his work published in 1790, which were the pre-Hispanic objects that could be admired in the city.

In 1988, the famous Moctezuma I Stone was discovered here in the old Archdiocese, on Moneda Street, where battles, etc. are also related, as well as the so-called Piedra de Tizoc.

On the other hand, in the Xochimilco Delegation there are chinampas of pre-Hispanic origin; Nahuatl is spoken in Milpa Alta and the neighbors defend it with enormous determination, since it is the main language spoken in Tenochtitlan.

We have many presences, and the most important symbolically speaking is the Shield and the Flag, as they are Mexican symbols, that is, the eagle standing on the cactus eating the snake, which some sources tell us that it was not a snake, but a bird, the important thing is that it is the symbol of Huizilopochtli, of the defeat of the sun against the nocturnal powers.

M.D. In what other aspects of daily life does the indigenous world manifest itself?

E.M. One of them, very important, is food; we still have many elements of pre-Hispanic origin or at least many ingredients or plants that are still used. On the other hand, there are those who maintain that the Mexican laughs at death; I sometimes ask in conferences that if Mexicans laugh when they witness the death of a relative, the answer is negative; in addition, there is a deep anguish before death. In the Nahua songs this anguish is clearly manifested.