Towards the IV-XI centuries of our era, several settlements flourished in the Sierra Gorda of Queretana.

Of these, Ranas and Toluquilla are the best known archaeological sites; In them you can admire sets of ritual foundations, residential buildings and ball courts, harmoniously integrated with the ridges of the hills. Cinnabar mines pierce nearby slopes; This mineral (mercury sulfide) was once highly esteemed for its brilliant vermilion color, similar to living blood. The abandonment of the mountains by sedentary settlers coincides with the collapse of agricultural settlements in much of Northern Mesoamerica. Later, the region was inhabited by the nomads of Jonaces, dedicated to hunting and gathering, and by the semi-sedentary Pames, whose culture had similarities with Mesoamerican civilization: the cultivation of corn, a stratified society and temples dedicated to the veneration of their gods. .

After the Conquest, some Spaniards came to the Sierra Gorda attracted by the favorable conditions for agricultural, livestock and mining companies. Consolidating this penetration of the New Hispanic culture required integrating the indigenous serranos into the socioeconomic and political system, a task entrusted to the Augustinian, Dominican and Franciscan friars. The first missions, during the 16th and 17th centuries, were not very effective. Around 1700, the sierra was still seen as "a stain of gentleness and barbarism," surrounded by incipient New Spanish populations.

This situation changed with the arrival in the Sierra Gorda of Lieutenant and Captain General José de Escandón, in command of the regiment of the city of Querétaro. Starting in 1735, this military man carried out a series of campaigns for the pacification of the mountains. In 1743, Escandón recommended to the viceregal government the total reorganization of the missions. His project was approved by the authorities and in 1744 missionary centers were established in Jalpan, Landa, Tilaco, Tancoyol and Concá, under the control of the Franciscans of the San Fernando Propaganda Fide college, in the capital of New Spain. The Pames who refused to live in the missions were subdued by Escandón's soldiers. In each mission a rustic wooden chapel with a grass roof was built, a cloister made of the same materials and huts for the indigenous people. In 1744 there were 1,445 indigenous people in Jalpan; the other missions had between 450 and 650 individuals each.

A company of soldiers was established in Jalpan, under the orders of a captain. In each mission there were soldiers to escort the friars, maintain order and capture the natives who were trying to escape. In 1748, Escandón's troops put an end to the resistance of the Jonaces in the battle of Media Luna hill. With this fact, this mountain town was practically exterminated. The following year, Femando VI, King of Spain granted Escandón the title of Count of the Sierra Gorda.

By 1750, conditions favored the evangelization of the region. A new group of missionaries arrived from the San Fernando College, under the orders of the Majorcan Brother Junípero Serra, who would spend nine years among the Pames Serrano as president of the five Fernandine missions. Serra began his work by learning the Pame language, into which he translated the basic texts of the Christian religion. Thus crossed the linguistic barrier, the religion of the cross was taught to the locals.

The missionary techniques used in the sierra were the same as those used by the Franciscans in other regions during the 18th century. These friars returned to some aspects of the evangelization project of New Spain of the 16th century, especially in the pedagogical and ritual aspects; They had, however, one advantage: the small number of indigenous people allowed greater control over them. On the other hand, the military played a much more active role in this advanced stage of the "spiritual conquest." The friars were the authorities in the missions, but they exercised their control with the support of the soldiers. They also organized an indigenous government in each mission: a governor, mayors, corporals, and prosecutors were elected. The faults and sins of the indigenous people were punished by whipping administered by the indigenous prosecutors.

There were sufficient resources, thanks to the intelligent administration of the friars, the work of the pames and a modest subsidy provided by the Crown, not only for subsistence and evangelization, but for the construction of five missionary masonry complexes, built between 1750 and 1770, which today amaze visitors to the Sierra Gorda. On the covers, richly decorated with polychrome mortar, the theological foundations of Christianity were reflected. Foreign master masons were hired to direct the works of the churches. In this regard, Fray Francisco Palou, companion and biographer of Fray Junípero, says: “After the venerable Fray Junípero saw his children the Indians in a state of working with greater enthusiasm than at the beginning, he tried to have them build a masonry church (.. ) He proposed his devoted thought to all those Indians, who gladly agreed, offering to carry the stone, which was at hand, all the sand, make the lime and mix, and serve as laborers for the masons (..) and in the time of seven years a church was completed (..) With the exercise of these works (the pames) were enabled of various trades, such as masons, carpenters, blacksmiths, painters, gilders, etc. (...) what was left over from the synod and from the alms of masses was used to pay the wages of the masons (...) ”. In this way Palou refutes the modern myth that these temples were created by missionaries with the sole support of the Pames.

The fruits of agricultural labors, carried out on communal lands, were kept in barns, under the control of the friars; a ration was distributed daily to each family, after prayers and doctrine. Each year larger harvests were achieved, until there were surpluses; These were used to buy teams of oxen, farm implements and cloth to make clothes. The larger and smaller cattle were also communally owned; the meat was distributed among all. At the same time, the friars encouraged the cultivation of private plots and the raising of livestock as private property. Thus, they prepared the pames for the day of the secularization of the missions, when the communal regime ended. The women learned to produce textiles and clothing, spinning, weaving and sewing. They also made duffel bags, nets, brooms, pots and other items, which their husbands sold in the markets of neighboring towns.

Every day, with the first rays of sun, the bells called the indigenous adults to the church to learn the prayers and Christian doctrine, most of the time in Spanish, others in Pame. Then the children, ages five and up, came in to do the same. The boys returned each afternoon to continue their religious learning. Also in the afternoon were the adults who were going to receive a sacrament, such as the first communion, marriage, or annual confession, as well as those who had forgotten some part of the doctrine.

Every Sunday, and on the occasion of the obligatory celebrations of the Church, all the natives had to attend mass. Each indigenous person had to kiss the friar's hand to register their attendance. Those who were absent were severely punished. When someone could not attend due to a commercial trip, they had to return with a proof of their attendance at mass in another town. On Sunday afternoons, the Crown of Mary was prayed. Only in Concá did this prayer take place during the week, taking turns every night to another neighborhood or ranchería.

There were special rituals to celebrate the main Christian holidays. There is concrete information on those held in Jalpan, during Junípero Serra's stay, thanks to the chronicler Palou.

Every Christmas there was a "colloquium" or play on the birth of Jesus. Throughout Lent there were special prayers, sermons, and processions. In Corpus Christi there was a procession between arches, with "... four chapels with their respective tables for the Lord in the Sacrament to pose". In the same way, there were special celebrations for other festivals throughout the liturgical year.

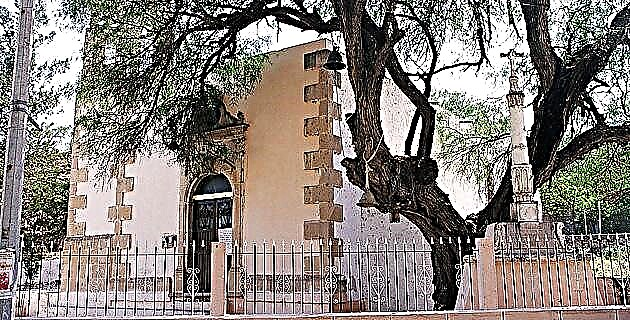

The golden age of the mountain missions ended in 1770, when the archbishop ordered their delivery to the secular clergy. The category of mission was conceived, during the 18th century, as a phase of transition towards the full integration of the indigenous people into the New Spain system. With the secularization of the missions, communal lands and other productive properties were privatized. The pames had, for the first time, the obligation to pay tithe to the archdiocese as well as taxes to the Crown. A year later, a good part of the Pames had already left the missions, returning to their old settlements in the mountains. The semi-abandoned missions fell into a state of decline. The presence of the missionaries from the Colegio de San Fernando lasted only five years. As witnesses to this stage of the conquest of the Sierra Gorda, there are the monumental national ensembles that now cause admiration and arouse interest in knowing the work of figures of the stature of Fray Junípero Serra.

Source: Mexico in Time No. 24 May-June 1998