With a mixture of deep religiosity, syncretism and a lot of color, one of the Otomí towns with the longest tradition holds its patronal festival on July 25, which is attended by neighbors from all over the southern tip of Querétaro.

With a mixture of deep religiosity, syncretism and a lot of color, one of the Otomi peoples with the longest tradition holds its patronal festival on July 25, which is attended by neighbors from all over the southern tip of Querétaro.

The mist settled heavily over the green valleys and mountains of the Amealco municipality as we zigzagged along the highway. –Where is Don going? The driver asked every time he stopped to load passengers. I'm going to Santiago. - Get on quickly, we're going.

The public transport service van was getting people up and down as we crossed the ranches, although most of us were going to the feast of the Apostle Santiago. It was early, the cold penetrated deep and in the Plaza de Santiago Mexquititlán a group of ranchera music arrived from neighboring Michoacán was playing spiritedly even when the only ones who were there were those in charge of sweeping the atrium of the church.

Bordering Michoacán and the State of Mexico, Santiago Mexquititlán is an Otomí population of 16,000 inhabitants that sits south of the state of Querétaro. Its residents live distributed in the six neighborhoods that make up the territory, whose axis is the Central District, where the church and the cemetery are located.

There are two versions about its foundation. According to the anthropologist Lydia van der Fliert, the pre-Hispanic settlement was founded in 1520 and belonged to the province of Xilotepec; Another version tells us that this community was created by indigenous people from the Mezquital valley, Hidalgo, which could coincide with its meaning in the Nahuatl language, which means place among mesquites.

A MULTICOLORED TEMPLE

I went straight inside the temple, where the darkness contrasted with the multi-colored altars, which in addition to being painted pink, yellow and red, presented an endless number of flowers and candles decorated with colored china paper. Several life-size religious images were posted next to the aisle and on the main altar that of Santiago Apóstol presided over the scene. The atmosphere could be cut with a knife, as the smoke from the incense added to the prayers covered everything around.

Men and women came and went from a side door, busy sweeping, arranging the altar, and tuning every detail for the celebration. Further inside, dark and almost hidden, an altar lit by hundreds of candles was carefully cared for; It was the altar of the mayordomos, who at that time ended the vigil requesting favors in the Otomí language –ñöñhö, hñäñho or ñhäñhä– from the Virgin of Guadalupe. Crouching in a corner trying to make myself invisible, I enjoyed the scene where the principals arranged every detail of the party and delegated functions to the freighters, who would put order at the time of offering to the saints. Little by little, the church nave began to fill with parishioners and suddenly a group of shell dancers interrupted the silence of the prayer offering their respects to the apostle.

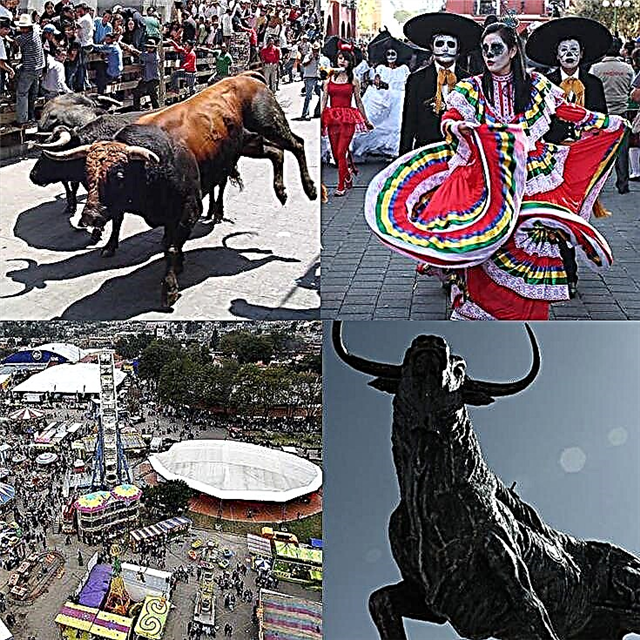

That day was a fair in the town. The fried food stalls and the mechanical games were the delight of the children, but the vintage of textiles, ceramics, vases, pots, jugs, lamps in the shape of church towers and many other crafts that entertained my gaze by good time.

By the time the ceremony was over, a group of women dressed in the purest Otomí style of Amealco began a dance accompanied by a drum and a violin as they allowed the multicolored skirts and ribbons of the hats that make up their dresses to form a magnificent kaleidoscope that flew through the air. Immediately a procession made up of the mayordomos from all the neighborhoods emerged from inside the temple carrying all the images, including that of Mr. Santiago. After surrounding the main square, the images were returned to the temple to carry out the mass for the patron saint, which takes place between songs, prayers and much incense.

ALL IN WHITE

At the same time, another celebration was held in the atrium. More than a hundred children from neighboring communities and from Santiago itself, all in white suits, made their first communion. When both ceremonies ended, the principals of the community and the active mayordomos met to change the positions of mayordomías and vassals, who will be responsible for organizing and defraying the expenses of the following festivities of the patron saint. When the discussions came to a good end and the appointments were agreed, the principals and guests participated in a meal in which the possible frictions that had occurred were dissipated and they enjoyed a delicious mole with chicken, red rice, burro or ayocote beans, fresh tortillas. made and good quantity of pulque.

Meanwhile, the bustle of the party continued in the atrium as the pyrotechnic fires were prepared to be lit for the night. Santiago Apóstol, in the dark interior of his temple, continued to be offered by the faithful, who placed flowers and bread on the altar.

The cold returned in the afternoon, and together with the sun the mist fell again on the hamlets that are scattered throughout the neighborhoods. I got into the public transport van and a lady sat next to me, carrying with her a piece of blessed bread that touched the image of the apostle. He would take him home to cure his spiritual ills until next year, when he will return to venerate, once again, his holy Lord Santiago.

THE FAMILY CHAPELS

In the Otomí communities of Amealco the family chapels are attached or immersed in the houses, many of them erected in the 18th and 19th centuries. Inside we can see a large amount of religious iconography with pre-Hispanic details in which syncretism is evident, as in the case of the Blas family chapel. It is possible to visit them exclusively with the authorization of the heads of the family or to admire a faithful copy that is exhibited in the Room of Indian Towns of the Regional Museum of the city of Querétaro.

Source: Unknown Mexico No. 329 / July 2004