Do you know how and when the first printing press was established in Mexico? Do you know who Juan Pablos was? Find out more about this important character and his work as a printer.

The establishment of the printing press in Mexico meant a necessary and indispensable enterprise for the dissemination of Western Christian thought. It demanded the conjunction of various elements geared towards the same ideal: to take into account the meaning of the risk of a long-term investment and to overcome with tenacity and determination other multiple difficulties. As central figures, sponsors and promoters of the printing press in our country, we have Fray Juan de Zumárraga, the first bishop of Mexico and Don Antonio de Mendoza, the first viceroy of New Spain.

The main players in the company include Juan Cromberger, a German printer established in Seville, owner of a prestigious publishing house with capital to establish a subsidiary in New Spain, and Juan Pablos, Cromberger's workshop officer, whom as a copyist or composer of letters From a mold, he had the confidence to found the printing press, and he was also pleased or attracted by the idea of moving to the new continent to establish the workshop of his employer. In return, he received a ten-year contract, one-fifth of the earnings from his work and the services of his wife, after subtracting the costs of moving and setting up the printing press in Mexico City.

Juan Pablos received 120,000 maravedis from Juan Cromberger for both the purchase of the press, ink, paper and other equipment, as well as the expenses of the trip that he would undertake with his wife and two other companions. The total cost of the company was 195,000 maravedís, or 520 ducats. Juan Pablos, of Italian origin whose name, Giovanni Paoli, we already know in Spanish, arrived in Mexico City together with his wife Gerónima Gutiérrez, between September and October 1539. Gil Barbero, a presser by trade, as well as a black slave.

With the support of his sponsors, Juan Pablos established the “Casa de Juan Cromberger” workshop in the Casa de las Campanas, owned by Bishop Zumárraga, located on the southwest corner of the streets of Moneda and closed in Santa Teresa la Antigua, today licensed Right, in front of the former archbishopric's side. The workshop opened its doors around April 1540, Gerónima Gutiérrez being a ruler of the house without bringing a salary, only its maintenance.

Cromberger's company

It was Viceroy Mendoza who granted Juan Cromberger the exclusive privilege of having a printing press in Mexico and bringing books from all the faculties and sciences; the payment of the impressions would be at the rate of a quarter of silver per sheet, that is, 8.5 maravedís for each printed sheet and one hundred percent of the profits in the books that I brought from Spain. These privileges undoubtedly responded to the conditions imposed by Cromberger who, in addition to being a skillful book merchant, had interests in mining activities in Sultepec, in cooperation with other Germans, since 1535. Juan Cromberger died on September 8, 1540, almost a year after started the printing business.

His heirs obtained from the king the confirmation of what had been agreed with Mendoza for a term of ten years, and the certificate was signed in Talavera on February 2, 1542. A few days later, on the 17th of that same month and year, the council of the Mexico City granted Juan Pablos the title of neighbor, and on May 8, 1543 he obtained a plot of land for the construction of his house in the neighborhood of San Pablo, on the street that went precisely towards San Pablo, behind the hospital of the Trinity. These data confirm Juan Pablos' desire to take root and remain in Mexico despite the fact that the printing business did not have the desired development, since there was a contract and exclusive privileges that created a difficult situation and impeded agility. required for the growth of the company. Juan Pablos himself complained in a memorial addressed to the viceroy that he was poor and jobless, and that he supported himself thanks to the alms he received.

Apparently the printing business did not meet the expectations of the Crombergers despite the favorable conditions they obtained. Mendoza, with the aim of favoring the permanence of the printing press, granted more lucrative grants in order to motivate the interest of the heirs of this printing house in the conservation of his father's workshop in Mexico. On June 7, 1542, they received a land cavalry for crops and a cattle ranch in Sultepec. A year later (June 8, 1543) they were again favored with two mill sites to grind and melt metal on the Tascaltitlán river, a mineral from Sultepec.

However, despite these privileges and grants, the Cromberger household did not serve the printing press as the authorities expected; both Zumárraga and Mendoza, and later the Audiencia of Mexico, complained to the king about the lack of compliance in the provision of essential materials for printing, paper and ink, as well as the shipment of books. In 1545 they asked the sovereign to demand that the Cromberger family fulfill this obligation by virtue of the privileges that had previously been granted to them. The first printing press with the name "House of Juan Cromberger" lasted until 1548, although from 1546 it stopped appearing as such. Juan Pablos printed books and pamphlets, mostly of a religious nature, of which eight titles are known made in the period 1539-44, and another six between 1546 and 1548.

Perhaps the complaints and pressures against the Crombergers favored the transfer of the printing press to Juan Pablos. Owner of this from 1548, although with large debts due to the onerous conditions in which the sale took place, he obtained from Viceroy Mendoza the ratification of the privileges granted to the former owners and later that of Don Luis de Velasco, his successor.

In this way he also enjoyed the exclusive license until August 1559. The name of Juan Pablos as a printer appears for the first time in the Christian Doctrine in the Spanish and Mexican languages, completed on January 17, 1548. On some occasions he added the of his origin or provenance: "lumbardo" or "bricense" as he was a native of Brescia, Lombardy.

The situation of the workshop began to change around 1550 when our printer obtained a loan of 500 gold ducats. He asked Baltasar Gabiano, his moneylender in Seville, and Juan López, a violent neighbor from Mexico who was traveling to Spain, to find him up to three people, printing officers, to practice his trade in Mexico.

In September of that same year, in Seville, a deal was made with Tomé Rico, shooter (pressmaker), Juan Muñoz composer (composer) and Antonio de Espinoza, letter founder who would take Diego de Montoya as an assistant, if they all moved to Mexico and work in the printing press of Juan Pablos for three years, which would be counted from his landing in Veracruz. They would be given the passage and food for the trip in the ocean and a horse for their transfer to Mexico City.

They are believed to have arrived in late 1551; however, it was not until 1553 that the shop developed the work on a regular basis. The presence of Antonio de Espinosa was manifested by the use of Roman and cursive typefaces and new woodcuts, achieving with these modalities to overcome typography and style in books and printed matter prior to that date.

From the first stage of the printing press with the name "at the Cromberger's house" we can cite the following works: Brief and more compendious Christian doctrine in Mexican and Spanish language that contains the most necessary things of our holy Catholic faith for the use of these natural Indians and salvation of their souls.

It is believed that this was the first work printed in Mexico, the Adult Manual of which the last three pages are known, edited in 1540 and ordered by the ecclesiastical board of 1539, and The Relationship of the frightful earthquake that has happened again in Guatemala City published in 1541.

These were followed in 1544 by the Brief Doctrine of 1543 intended for everyone in general; the Tripartite of Juan Gerson which is an exposition of the doctrine on the commandments and the confession, and has as an appendix an art of dying well; the brief Compendium that deals with how the processions will be held, aimed at reinforcing the prohibitions of profane dance and rejoicing in religious festivals, and the Doctrine of Fray Pedro de Córdoba, directed exclusively to the Indians.

The last book made under the name of Cromberger, as the publishing house, was the short Christian Doctrine of fray Alonso de Molina, dated 1546. Two works published without the name of the printer, were the most true and true Christian Doctrine for people without erudition and letters (December 1546) and the short Christian Rule to order the life and time of the Christian (in 1547). This transition stage between one workshop and the other: Cromberger-Juan Pablos, was perhaps due to the initial transfer negotiations or to the lack of fulfillment of the contract established between the parties.

Juan Pablos, the Gutenberg of America

In 1548 Juan Pablos published the Ordinances and compilation of laws, using the coat of arms of Emperor Charles V on the cover and in the various editions of Christian doctrine, the coat of arms of the Dominicans. In all the editions made up to 1553, Juan Pablos adhered to the use of the Gothic letter and the large heraldic engravings on the covers, characteristic of Spanish books from that same period.

The second stage of Juan Pablos, with Espinosa at his side (1553-1560) was brief and prosperous, and consequently brought a dispute over the exclusivity of having the only printing press in Mexico. Already in October 1558, the king granted Espinosa, together with three other printing officers, the authorization to have his own business.

From this period, several works by Fray Alonso de la Veracruz can even be cited: Dialectica resolutio cum textu Aristótelis and Recognitio Summularum, both from 1554; the Physica speculatio, accessit compendium sphaerae compani of 1557, and Speculum coniugiorum of 1559. From Fray Alonso de Molina the Vocabulary in Spanish and Mexican appeared in 1555, and from Fray Maturino Gilberti the Dialogue of Christian doctrine in the Michoacán language, published in 1559.

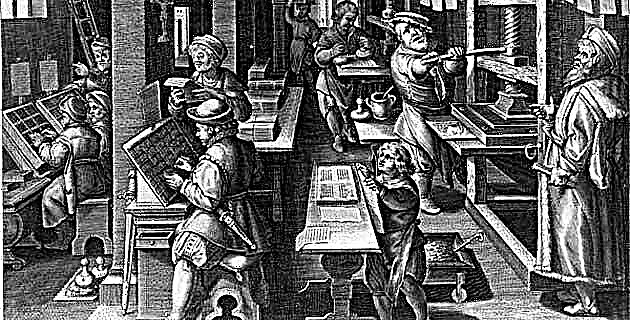

Reproduction of Gutenberg's printing press. Taken from the brochure of the Gutenberg Museum in Mainz, Col. Juan Pablos Museum of Graphic Arts. Armando Birlain Schafler Foundation for Culture and Arts, A.C. These works are in the collection guarded by the National Library of Mexico. The last printing by Juan Pablos was the Manual Sacramentorum, which appeared in July 1560. The printing house closed its doors that year, as it is believed that the Lombard died between the months of July and August. And in 1563 his widow leased the printing press to Pedro Ocharte married to María de Figueroa, daughter of Juan Pablos.

35 titles of the supposed 308 and 320 that were printed in the 16th century are attributable to the first stage of the printing press, with Cromberger and Juan Pablos as editors, indicative of the boom that the printing press had in the second half of the century.

The printers and also booksellers that appear in this period were Antonio de Espinosa (1559-1576), Pedro Balli (1575-1600) and Antonio Ricardo (1577-1579), but Juan Pablos had the glory of having been the first printer in our country.

Although the printing press in its beginnings published mainly primers and doctrines in indigenous languages to attend to the Christianization of the natives, by the end of the century it had covered subjects of a very diverse nature.

The printed word contributed to the diffusion of Christian doctrine among the natives and supported those who, as evangelizers, doctriners and preachers, had the mission of teaching it; and, at the same time, it was also a means of diffusion of indigenous languages and their fixation in the "Arts", as well as of the vocabularies of these dialects, reduced by the friars to Castilian characters.

The printing press also fostered, through works of a religious nature, the strengthening of the faith and morals of the Spaniards who came to the New World. Printers notably ventured into issues of medicine, ecclesiastical and civil rights, natural sciences, navigation, history and science, promoting a high level of culture socially in which great figures stood out for their contribution to universal knowledge. This bibliographic heritage represents an invaluable legacy for our current culture.

Stella María González Cicero is a doctor in History. She is currently the director of the National Library of Anthropology and History.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Encyclopedia of Mexico, Mexico, special edition for Encyclopedia Britannica de México, 1993, t.7.

García Icazbalceta, Joaquín, Mexican Bibliography of the 16th century, edition by Agustín Millares Carlo, Mexico, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1954.

Griffin Clive, Los Cromberger, the story of a 16th century printing press in Seville and Mexico, Madrid, editions of Hispanic Culture, 1991.

Stols Alexandre, A.M. Antonio de Espinosa, the second Mexican printer, National Autonomous University of Mexico, 1989.

Yhmoff Cabrera, Jesús, The Mexican prints of the 16th century in the National Library of Mexico, Mexico, National Autonomous University of Mexico, 1990.

Zulaica Gárate, Roman, Los Franciscanos and the printing press in México, México, UNAM, 1991.