One of our experts gives you a look at the period from 1930 to 1934 when, from being an unfinished project, this property became the most impressive in the Historic Center of Mexico City.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Porfirio Díaz commissioned the Italian architect Adamo Boari the project of an imposing National theater that would replace the one raised during the time of Santa Anna and would give a greater shine to his regime. The work was not completed according to its original intention, for reasons that ranged from economic (cost increase), technical (the collapse of the building that was noted from the first years of its construction), to political (the outbreak of the revolutionary movement started in 1910). From 1912 on, the decades passed without significant progress in the work. Finally, in 1932, Alberto J. Pani, then Secretary of the Treasury, and Federico Mariscal -Mexican architect, disciple of Boarii- assumed the responsibility of finishing the already old building. They soon realized that it was not strictly a matter of completing the Porfirian theater, but of thinking carefully about the new destiny of the building after the important changes experienced by Mexico, particularly in the cultural field. In a 1934 document, Pani and Mariscal narrate the story:

"The construction of the Palace of Fine Arts has gone through countless incidents over a long period of thirty years that coincide in our history with a radical transformation of society."

“From the moment, in 1904, when the foundations of what should have been the sumptuous National Theater were laid, until the moment, in the year 1934, when everything was opened to the people, for their service, a Palace of Fine Arts, such profound changes have occurred that they are still reflected in the history of construction. "

Next, Pani and Mariscal go back to the first two eras of the construction of the theater, in the initial decades of the century, to deal with the period in which they acted, which now interests us:

“In the third period, which includes only the years from 1932 to 1934, the new conception is gestated and realized. The name of Palace of Fine Arts defines it clearly enough to warn that not only has the National Theater of the Porfirian aristocracy disappeared - at least as it was originally conceived - but that the Nation has been provided with an indispensable center to organize and present its artistic manifestations of all kinds, theatrical, musical and plastic, not scattered and ineffective as up to now, but duly articulated in a coherent whole that can be called Mexican art.

This is the idea with which the revolutionary regime, reached its fullness, instead of completing the National Theater, has actually built a new building - the Palace of Fine Arts - that will no longer host the evenings of an impossible aristocracy, but the concert, the conference, the exhibition and the show, which mark the ascension of an art like ours every day ... "

The document insists on the position taken by Pani:

“… If the work does not respond to a social need, it can be permanently abandoned. It is not a question now of concluding it by concluding it, but rather of examining to what extent the economic sacrifice that its conclusion demands is imposed. "

Finally, Pani and Mariscal make a detailed description of the modifications imposed on the Boari project to give the building the new use that they considered indispensable. These modifications refer to the changes necessary to allow the palace to fulfill its great diversity of functions. This idea was revolutionary for the time, and although we are now used to it we must not lose sight of the fact that the primordial place that this building has occupied since then in Mexican culture is directly linked to the metamorphosis that its conception underwent in 1932. The bustling activity that takes place during the day in the Palace of Fine Arts, with the public that attends to visit its temporary exhibitions, to admire its murals (those of Rivera and Orozco were commissioned for the inauguration of the Palace in 1934; later those of Siqueiros, Tamayo and González Camarena), to the presentation of a book or to listen to a conference, it would be unthinkable if the building had been finished according to the purposes of Porfirio Díaz. The conception of Pani y Mariscal is an excellent testimony to the cultural creativity that Mexico fully experienced in the decades that followed the Revolution.

Pani himself had intervened in 1925 in the gestation of another national institution born of the Revolution: the Bank of Mexico, also housed in a Porfirian building whose interior was modified for its final destination by Carlos Obregon Santacilia using the decorative language now known as art deco. As in the case of the Palace of Fine Arts, the birth of the bank made it necessary to give it, as far as possible, a face according to the new era.

Throughout the first decades of the 20th century, architecture and the decorative arts searched the world for new paths, urging a renewal that the 19th century had not been able to find. Art nouveau was a failed attempt in this regard, and from it, a Viennese architect, Adolf loos, would proclaim in 1908 that all ornament should be considered a crime.

With his own work, he laid the foundations of the new rationalist architecture, of concise geometric volumes, but also established, with another Viennese, Josef Hoffmann, the fundamental lines of Art Deco, which would be developed in the 1920s as a reaction to more radical proposals.

Doesn't enjoy the art deco of critical good fortune. Most of the stories of modern architecture ignore or disdain it for its anachronism. Serious historians of architecture dealing with it do so only in passing, and this attitude may not change in the future. The Italians Manfredo Tafuri Y Francesco Dal Co, authors of one of the most solid histories of 20th century architecture, dedicate a couple of paragraphs to Art Deco which, in short, are perhaps the best characterization that can be made of this style. They analyze, first of all, the reasons for their success in the United States:

“… The decorative and allegorical motifs exalt easily assimilable values and images, always starting from rigidly predetermined solutions on the economic and technological level. [..] Art Deco architecture adapts to the most diverse situations: the eccentricity of its decorations satisfies the advertising intentions of large companies and a solemn symbolism qualifies corporate headquarters and public buildings. The luxurious interiors, the strenuous play of the ascending lines, the recovery of the most varied ornamental solutions, the use of the most refined materials, all this is adequate to incorporate a new “taste” and a new “quality” of masses to the flow. chaotic of metropolitan consumption. "

Tafuri and dal Co also analyze the context of the Paris Exposition of 1925 that put Art Deco into circulation.

“In essence, the operation was reduced to the launch of a fashion and a new taste of the masses, capable of interpreting the typically bourgeois ambitions of renewal, without falling into provincialism but offering a guarantee of moderation and easy assimilation. It is a taste that will achieve enormous influence in a wide sector of North American architecture, ensuring, in France, a calm mediation between avant-garde and tradition. "

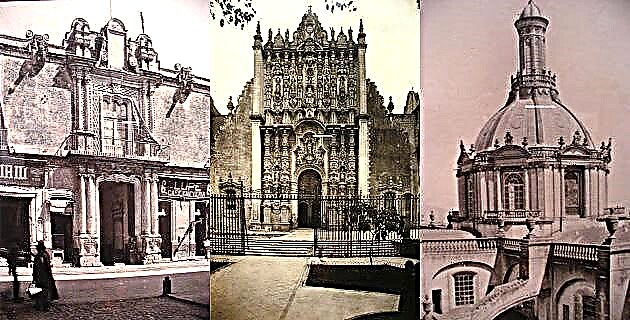

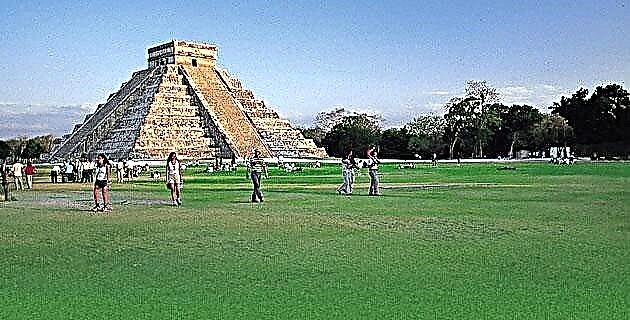

It is precisely this situation of compromise between the avant-garde and the past that made Art Deco particularly suitable for completing a building like the Palace of Fine Arts, begun thirty years ago in the language of a now extinct tradition. The very high void under the domes that cover the great hall of the building, around which the exhibition spaces revolve, allowed to display in it, in a spectacular way, “the strenuous play of the ascending lines”. The nationalist currents present then in Mexican art would also find in Art Deco the adequate support to apply in the Palace "the decorative and allegorical motifs [that] exalt easily assimilable values and images", taking advantage of every opportunity to surprise us with "the eccentricity of its decorations ”and“ a solemn symbolism ”, without forgetting“ the recovery of the most varied ornamental solutions [and] the use of the most refined materials ”. No better words can be found than the above to describe, among other ornaments, the Mexican motifs -Mayan masks, cacti-, polished steel and bronze that attract the attention of visitors to the Palace.

A nephew of Alberto J. Pani, the young architect Mario Pani, recently graduated from the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, served as a link for the French firm Edgar Brandt, very prestigious and whose boom coincided precisely with Art Deco, to provide the aforementioned decorative elements (to which we must add doors, doors, railings, handrails, lamps and some pieces of furniture) that are such an important part of the decoration of the performance hall, the lobby and the exhibition areas. The rest of the impressive effect of these spaces was achieved with a remarkable display of rare colored national marble and onyx. Finally, the cladding of the dome that finishes off the exterior of the Palace was designed in the same style by Roberto Alvarez Espinoza using copper ribs on the metal reinforcement and ceramic coatings of metallic tones and angular geometry in the segments that separate the ribs. These domes, whose chromatic gradation goes from orange to yellow and white, constitute one of the most characteristic features of the Palace and represent the most important expression of Art Deco on the outside.

But it is not only the successful effect that was obtained in the building, with the exquisite decoration that allowed it to be completed, that should now call our attention. As already mentioned, it should be remembered that after the marvelous Art Deco marbles, steels, bronzes and crystals that we see now, one of the most original artistic dissemination projects carried out has also risen since its inauguration on September 29, 1934. anywhere in the world, conceived -not by chance- during a moment of particular intensity in the cultural history of our country: the Palace of Fine Arts.