Within this scenario, considered as a Biosphere Reserve - the richest in diversity among the country's reserves - are the five Franciscan missions of the Sierra Gorda founded and established in the mid-18th century.

The remarkable singularity of this indigenous-tinged baroque can be seen in their very names: Santiago de Jalpan, Nuestra Señora de la Luz de Tancoyotl, San Miguel Concá, Santa María del Agua de Landa and San Francisco del Valle de Tilaco.

This beautiful, and for a long time impassable region, was a kind of natural refuge for the human groups that lived here: pames, jonaces, guachichiles, all of them known under the generic name of chichimecas. And it is that in a certain way, this imposing geography imposed its conditions on viceregal history. The five Franciscan missions found here are unique both for their history and for their architectural creation, an atypical baroque that is like the consummation of miscegenation, a European project built freely by indigenous hands and imagination. A true encounter. The missions are on the one hand the crystallization of a great humanist aspiration headed by Fray Junípero Serra, the missionary of Mallorcan origin who tried to be as radical as his spiritual father Francisco de Asís, and on the other hand the late, and let's say so, desperate advanced military captained by José de Escandón.

Let us think of a fact that we suppose hurt Spanish pride, until 1740 the viceroyalty had not managed to "pacify" the populations of this region with the cross and the sword. A nation of nations conquered and subdued 200 years ago by the power of the Spanish crown and yet a small and close territory to the viceregal capital that still remained indomitable. "What a shame!" Some powerful people may have thought; So Escandón undertakes, in 1742, the siege of all the rebel groups of the Sierra Gorda; hence the fury with which the last offensive, the ominous battle of the Media Luna, was launched in 1748, a brutal epilogue in which the captain almost exterminated all these groups.

In the midst of these circumstances, in 1750 a group of Franciscan missionaries led by Fray Junípero Serra arrived at the town of Jalpan. His mission, evangelize the Indians and complete with the cross and the word the tasks started by Escandón with the weapons. But Fray Junípero, worthy heir of the poor man of Assisi, brought with him a very different missionary project and in total opposition to the ideas promoted by the captain in the previously founded missions. Along with the notions of poverty and communion –in its deepest sense– typical of Saint Francis, Fray Junípero carried the utopian ideals of the best European humanism of the time. To the climate of violence and hostility and growing distrust with which he had to be received by the various indigenous groups, Junípero opposed a firm missionary attitude that consisted of accompanying and understanding his social problems, in the knowledge of his hunger and his language. As the anthropologist Diego Prieto told us, Junípero founded cooperatives and supported and strengthened their organizational and production capacities, motivated the distribution of land and not only did not impose Spanish when evangelizing, but also carried out his doctrinal tasks in the language pame. It was therefore a missionary task of great dimensions and profound consequences from the human point of view and whose results are today appreciable in the baroque syncretism exhibited by this harmonious and unique set of missions.

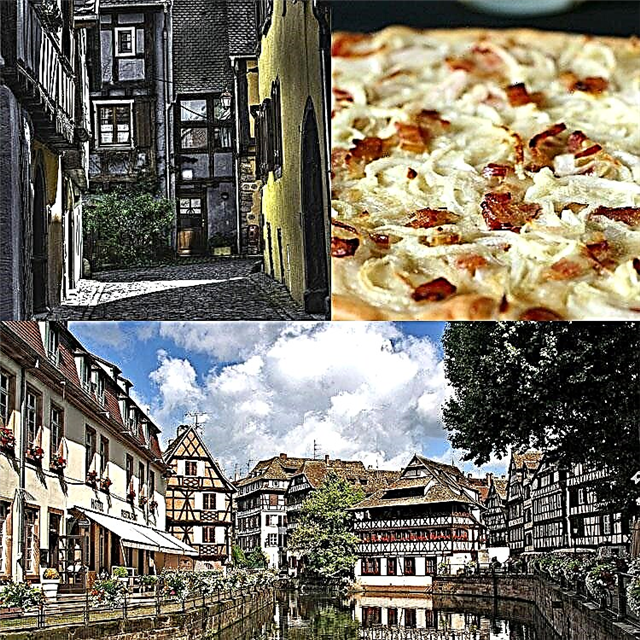

THE MESTIZO BAROQUE

At present, when it comes to the Missions of the Sierra Gorda, the first thing one thinks of is the five buildings, the five temples. There they are, you have to see them, you have to stop a little longer and contemplate them, the five beautiful missions. But as you will have noticed, they are the result of a complex and rich historical process of mutual evangelization, to call it somehow. What we see today in each of them, in each altarpiece, is the product of that profound encounter between two human groups of radically different nature. The conception of the world, religion, the notion of faith, deities, animals and light, the color and complexion of bodies and faces, food, eroticism, everything was so different among the friars they brought with them to Europe and the Indians who were in their land, but who had been confined, stripped and overwhelmed. Something, however, united them, one of those strange or rather marginal moments in the stories of conquest from one civilization to another: respect, recognition of difference. There a utopia was being forged, a small group of Europeans recognizing the other, hurt to the root in their dignity by their own European peers.

UNIQUE BEAUTY

Thus, the missions that we appreciate today are astonishing for their singular beauty, but this is the plastic and architectural manifestation of that encounter, of that solar moment of human radiation, where the temple was the home of a group of peoples, the nucleus of a series of activities that started from there or ended there. That was what the missions were at that time, not the building but the vision of things, the look reflected in the temple, the new order that I suppose they were looking for with amazement and difficulty, the tasks that could be of farming, of mutual aid, of energetic defense against injustice, evangelization.

That is why perhaps this architectural miscegenation, this unparalleled baroque is so admirable, because each facade-altarpiece is precisely that, a vision, a staging of that moment of contact and communion, yes, but where it was also manifested, and of exceptionally, the difference. Concá is a pame word that means “with me”, but that in the mission also bears the name of San Miguel; there is Saint Michael the Archangel crowning the façade and on one side, a rabbit that does not have Christian symbolism but does pame. There is the Virgin of Pilar and the Virgin of Guadalupe in the Jalpan Mission, which we all know has deep Mesoamerican roots, and a double-headed eagle that mixes meanings. There is the rich vegetal ornamentation and the profusion of ears in Tancoyotl; the catholic saints of Landa or Lan ha, together with the mermaids or faces with unmistakable native lines. There is Tilaco at the bottom of a valley reminiscent of José María Velasco, with his little angels, his ears of corn and his strange vase, which finishes off the entire composition, above San Francisco.

Fray Junípero Serra only lasted eight years in this project, but his utopian dream lasted until 1770, when various historical circumstances –such as the expulsion of the Jesuits– led in part to the abandonment of the missions. He, however, continued his evangelizing mission and his Franciscan ideal until the end of his days in Alta California. The Franciscan missions of the Sierra Gorda, the “five sisters”, as Diego Prieto and the architect Jaime Font call them, are a wonderful legacy of that frontal struggle to make utopia possible. Since 2003, the five sisters are considered World Heritage of Humanity. From a distance, Fray Junípero and the Franciscan missionaries, and the Pames, the Jonaces, and the Chichimecas, who built these missions and that life project, seem to us increasingly larger.

THE SIERRA GORDA

It was decreed as a Biosphere Reserve on May 19, 1997, to later be recognized as one of the Areas of Importance for the Conservation of Birds by the International Council for the Preservation of Mexican Birds, and being the 13th. Mexican reserve to join its International Network of Biosphere Reserves through the "Man and the Biosphere" Program of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

It is located in the physiographic sub-province called Carso Huasteco, an integral part of what is the great mountain chain known as Sierra Madre Oriental.

The region declared as a Biosphere Reserve is located northeast of the state of Querétaro de Arteaga, encompassing the municipalities of Jalpan de Serra, Landa de Matamoros, Arroyo Seco, Pinal de Amoles (88% of its municipal territory) and Peñamiller (69.7% of its territory). It is monitored by Conanp.