Dotted with colorful swarms of balloons, tireless boleros and cylinders eager to stand out, the Alameda is host to walkers, children, lovers and those who, for want of doing something better, occupy a bench.

Although it is forbidden to step on the grass, green invites rest and full expression of Sunday and festive arrangements: the bathed body, the fragrant hair and the luminous outfit (surely new) propitiate the party in a horizontal position, there next to a figure white that appears timid in her marbled nakedness, caressing a dove clinging to the stone breast. Further on, two gladiators prepare for the fight in a restrained attitude in very white ways. Suddenly, in front of them, a girl runs past, shaking the pink of an excessive "cotton", which in the distance turns into a shy little spot, into fleeting confetti.

And in the sultry sunny day of 12:00 noon, when the ritual of the usual weekends is fulfilled, it seems that the Alameda has always been like this; that with that appearance and that life he was born and with them he will die. Only an extraordinary event, an imbalance that breaks the imposed rhythm: an earthquake, the destruction of a sculpture, a protest march, the nightly assault on a passerby, will make someone wonder if time has not passed through the Alameda.

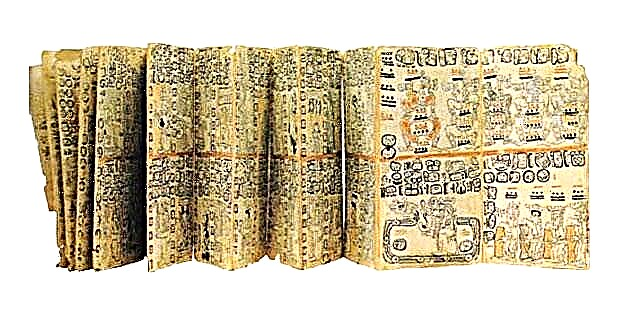

The historical memory reconstructed through decrees, sides, letters, travelers' narratives, news reports, plans, drawings and photographs indicate that the effects of time on the life of a society have altered the appearance of the Alameda. His old biography dates back to the 16th century when, on January 11, 1592, Luis de Velasco II ordered the construction of an alley on the outskirts of the urban area where, obviously, poplars had to be planted, which ultimately turned out to be ash trees.

Considered the first Mexican walk, the elite of New Spain's society would gather in the labyrinthine garden. So that barefoot people would not tarnish the green mirage of the wealthy, in the 18th century a fence was placed along its entire periphery. It was also at the end of that century (in 1784) when the circulation of the cars that passed along its roads on holidays was regulated, after having the exact number of the large number of cars in the capital city: six hundred thirty-seven . In case anyone doubted that such a figure was real, the authorities announced that the people from whom the data were obtained were to be trusted.

With the nineteenth century, modernity and culture took over the Alameda: the first as a symbol of progress and the second as a sign of prestige, two reasons for confidence in the future that the recently liberated society sought. For this reason, trees were planted repeatedly, benches were installed, cafes and ice cream parlors were erected, and lighting was improved.

The military bands widened the atmosphere of the park and the umbrellas contracted the gaze that then moved to a loot or the fallen handkerchief, and came back up from the tip of a cane. The Lord Regidor de Paseos, strutted with his municipal office and obtained fame for his arboreal reforms and for his imagination applied to the trickle of the fountains in the fountains. But the objections starred in bitter controversy when the culture took the form of Venus, since the pious Porfirian society did not notice the beauty but the lack of clothes of that naked woman in a park and in full view of all. Actually, in that year of 1890, culture was making efforts to take over, even if it was a very small area, of the renowned promenade of the capital.

The Statuary

Already in the twentieth century, it could be thought that the attitude towards a statuary that recreates the human body has changed, that the reeducation of citizens beyond school and home, in movie theaters or at home in front of the television, it has opened the sensitivity to the beauty of the language that the artist's imagination provides with spaces and human forms. The sculptures present for years in the Alameda give an account of this. Two gladiators in a combat attitude, one half covered with a cape that hangs from his arm and the other in frank nudity, share the wooded background with a Venus with a delicate attitude that a cloth recovers when covering the front of her body, and is reiterated by the presence of two pigeons.

Meanwhile, on two low pedestals, at the hand of those who circulate on Avenida Juárez, lie the figures of two women who develop in the marble with their bodies face down: one with her legs bent into a ball and her arms straight next to the head hidden in an attitude of sadness; the other, in tension with a frank attitude of struggle against the chains that subjected her. Their bodies do not seem to surprise the passerby, they have caused neither joy nor anger for decades; simply, indifference has relegated these figures to the world of objects without direction or meaning: pieces of marble and that's it. However, in all those years in the open they suffered mutilations, they lost their fingers and noses; and malicious "graffiti" covered the bodies of those two recumbent women named Désespoir and Malgré-Tout in French, following the fashion of the turn of the century world into which they were born.

Worse fate dragged the Venus to its total destruction, because one morning it woke up annihilated with hammer blows. An enraged madman? Vandals? No one answered. By all means, the pieces of the Venus stained white the floor of the very old Alameda. Then, silently, the fragments disappeared. The corpus delicti vanished for posterity. The naive little woman sculpted in Rome by a sculptor who was almost a child: Tomás Pérez, a disciple of the Academy of San Carlos, sent to Rome to, according to the program of pensioners, perfect himself at the Academy of San Lucas, the best in the world, the center of classical art where German, Russian, Danish, Swedish, Spanish artists arrived and, why not, Mexicans who had to return to give glory to the Mexican nation.

Pérez copied the Venus from the Italian sculptor Gani in 1854, and as a sample of his advances he sent it to his Academy in Mexico. Later, in one night, his effort died at the hands of backwardness. A more benign spirit accompanied the four remaining sculptures from the old walk to their new destination, the National Museum of Art. Since 1984 it has been commented in the newspapers that the INBA had the intention of removing the five sculptures (there was still the Venus) from the Alameda to restore them. There were those who wrote asking that their removal should not be the cause of major disasters, and who denounced their deterioration advising that the DDF hand them over to INBA, since since 1983 the Institute had expressed its interest in placing them in the hands of professional restorers. Finally, in 1986, a note affirms that the sculptures sheltered since 1985 in the National Center for the Conservation of Artistic Works of the INBA will no longer return to the Alameda.

Today they can be admired perfectly restored in the National Museum of Art. They live in the lobby, an intermediate place between their former world in the open air and the Museum's exhibition rooms, and they enjoy constant care that prevents their deterioration. The visitor can calmly surround each of these works, free of charge, and learn something about our immediate past. The two life-size gladiators, created by José María Labastida, fully display the classic taste so in vogue at the beginning of the 19th century. In those years, in 1824, when Labastida worked in the Mexican Mint, he was sent by the Constituent Government to the renowned Academy of San Carlos to train in the art of three-dimensional representation and return to create monuments and images. that the new nation needed, both for the formulation of its symbols and for the exaltation of its heroes and culminating moments in the history that was to be created. Between 1825 and 1835, during his stay in Europe, Labastida sent these two gladiators to Mexico, which can be thought of as an allegorical reference to the men who fight for the good of the nation. Two wrestlers treated with a calm language, with soft volumes and smooth surfaces, collect in a complete version each of the nuances of the masculine muscles.

In contrast, the two female figures recreate the taste of the Porfirian turn-of-the-century society that has its eyes set on France as the champion of modern, cultured and cosmopolitan life. Both reproduce the world of romantic values, pain, despair and torment. Jesús Contreras when giving life to Malgré-Tout around 1898, and Agustín Ocampo when creating Désespoir in 1900, use a language that speaks of the female body -released to second term by the classical academies-, combining smooth and rough textures, languid women on rough surfaces. Contrasts that call for the experience of immediate emotion over the reflection that comes later. Without a doubt, the visitor will feel the same call, from the back of the hall, when contemplating Aprés l’orgie by Fidencio Nava, a fin-de-siècle sculptor who has worked with the same formal taste on the fainted woman in his work. An excellent sculpture that, thanks to the intervention of its Board of Trustees, this year has become part of the collection of the National Museum of Art.

An invitation to visit the Museum, an invitation to know more about Mexican art are these nudes that live indoors and whose bronze imitations were left in the Alameda.