A snake with vegetable scales accompanies us. They are the hills that seem to devour the road: their undulating crest is drawn against a cloudless sky and the sun scorches the sugar cane fields that reach the foot of the mountains in green waves.

This is the dirt road where the archaeologist Fernando Miranda, from the INAH Regional Center of Veracruz, leads us to one of the sacred sites of the Totonacs.

The smile of the ceramic figurines, of which so many have come out of the ground in this area, seems to be reflected in the exuberance of the landscape. Its echo is perceived among the gusts of a warm wind, and it tells us that the people that inhabited the valleys we crossed must have had few shortcomings: for this reason the remains show faces that have lost any rigidity and are the portrait of men always happy, who surely the song and dance accompanied at all times. We are in the Atoyac valley, close to the town of the same name in the state of Veracruz.

The truck stops and Fernando shows us the way to a stream. We must cross it. Following the archaeologist, who has conducted several excavations in the area, we come to a log that is used as a bridge. Looking at it, we doubt our ability to balance on such a small and uneven surface. And it is not that the fall was dangerous, but that it implied going to stop with everything and photographic equipment, to a pool of uncertain depth. Our guide reassures us as he takes a long perch out of the vegetation, introduces it into the water and, leaning on that branch - a precarious substitute for a railing - shows us a safer way to cross. The gap on the opposite side enters the coolness of the always shady coffee plantations, which contrast with the scorching sun of the nearby cane fields. We soon arrived at the banks of a river with blue currents that undulate between logs, lilies and sharp-edged rocks. Beyond, the hills of a low chain are seen again, announcing the great elevations of the mountainous system of central Mexico.

At last we reach our destination. What was presented before our eyes exceeded the descriptions that had been made of this place full of magic. In part it reminded me of the cenotes of Yucatan; however, there was something that made it different. It seemed to me the very image of Tlalocan and since then I have no doubt that a place like this was the one that inspired the pre-Hispanic ideas of a kind of paradise where the water gushed from the bowels of the hills. There each accident, each facet of nature acquired divine proportions. Landscapes like this surely underwent a metamorphosis in the mind of man to become super-terrestrial sites: to put it in the words of the wise father José Ma. Garibay, it would be the mythical Tamoanchan that Nahua poems speak of, the site of the jade fish where the flowers stand tall, where the precious lilies are budding. There the song is sung among the aquatic moss and multiple trills make the music vibrate on the turquoise feathers of the water, in the midst of the flight of iridescent butterflies.

The Nahua verses and ideas about paradise are joined, at the source of the Atoyac river, by archaeological findings. Some years ago, the teacher Francisco Beverido, from the Institute of Anthropology of the Veracruzana University, told me how he directed the rescue of a valuable stone yoke profusely carved that today is near there, in the Museum of the city of Córdoba, a site worth visiting. The yoke was thrown as an offering to the water gods by peoples who inhabited the surrounding areas. A similar ceremony was held in the Yucatecan cenotes, in the lagoons of the Nevado de Toluca and in other places where the most important gods of the Mesoamerican pantheon were worshiped. We can imagine the priests and ministers on the banks of the pool at the moment when, among the copal scrolls of the incense, they threw valuable offerings into the water while asking the deities of the vegetation a good year for the crops.

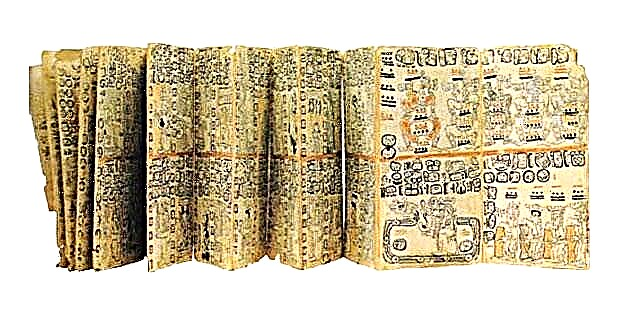

We did not resist the temptation and we jumped into the water. The perception of the icy liquid, its temperature is about 10ºC, was accentuated due to the oppressive heat that had made us sweat all the way. The pool must be about 8m deep in the deepest part and visibility does not reach more than 2m, due to the sediments that the water carries from the interior of the hill. The underwater grotto from which it flows resembles enormous jaws. It is the same image of the Altépetl of the codices, where a stream flows from the base of the figure of the hill through a kind of mouth. It is like the jaws of Tlaloc, god of earth and water, one of the most important and ancient numbers in Mesoamerica. It resembles the mouths of this god, which drain the precise liquid. Caso tells us that it is "the one that makes sprout" something more than evident in the sources of Atoyac. Being in this place is like going to the very origin of the myths, the worldview and the pre-Hispanic religion.

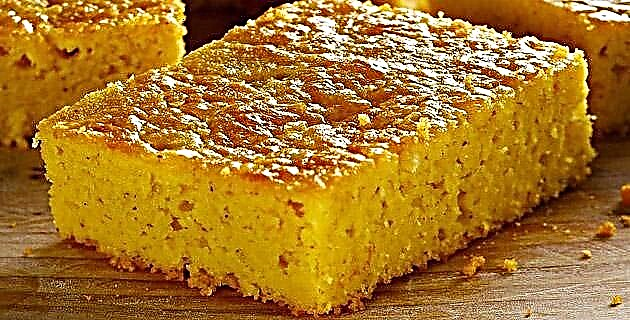

The region, it is worth remembering, was inhabited by a very representative culture of the Gulf of Mexico coast during the Classic period. The language they spoke during that time is unknown, but they were undoubtedly related to the builders of El Tajín. The Totonacs appear to have arrived in the area at the end of the Classic and early Post-Classic periods. Between the beaches of the Gulf of Mexico and the first foothills of the Transversal Volcanic Axis, a territory extends whose natural wealth attracted man since he first heard what we know today as Mexican territory. The Aztecs called it Totonacapan: the land of our maintenance, that is, the place where the food is. When hunger arose in the Altiplano, the hosts of Moctecuhzoma el Huehue did not hesitate to conquer these lands; this happened in the middle of the 15th century. The area would then be under the head of Cuauhtocho, a nearby site, also on the banks of the Atoyac, which still conserves a tower - fortress that dominates the river.

It is a place where color and light saturate the senses, but also, when the north hits the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, it is the Atlayahuican, the region of rain and fog.

Only with this humidity that stifles the elderly, can the panorama be kept always green. The Atoyac springs from the darkness of the caves, from the very bowels of the hill. The water comes to light and the impetuous current continues, like a turquoise snake, sometimes between violent rapids, towards the Cotaxtla, a river that becomes wide and calm. One kilometer before reaching the coast, it will join the Jamapa, in the municipality of Boca del Río, Veracruz. From there they both continue to their mouth in the Chalchiuhcuecan, the sea of the companion of Tláloc, of the goddess of water. Evening was falling when we decided to retire. Again we observe the slopes of the hills full of tropical vegetation. In them life pulses like the first day of the world.

Source: Unknown Mexico No. 227 / January 1996