It was the year 900. In the heat of a switched off smelting furnace, an old goldsmith told his young companions how the use of metal had begun among the Mixtecs.

He knew from his ancestors that the first metal objects had been brought by merchants from distant lands. This was many years ago, so many that there was no longer any memory. These merchants, who still visit the coasts, brought many objects to exchange; They came in search, among other things, of red bivalve shells and snails, highly esteemed in their religious ceremonies.

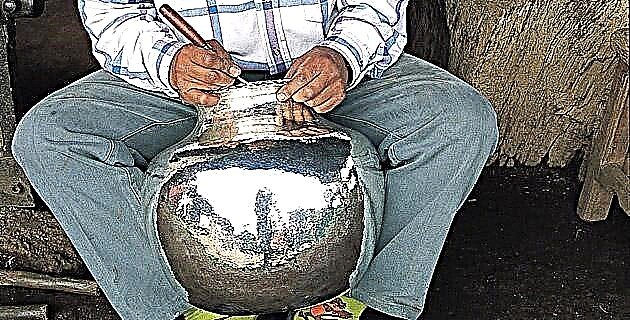

In the beginning, metal was hammer-forged; later, in addition to beating it cold, it was subjected to fire so that it did not become brittle. Later, foreign merchants taught us goldsmiths how to make molds and melt metal: they brought beautiful pieces that shone like the sun. They also showed us how the rivers contained the resplendent yellow diziñuhu in their waters; They had enough time to do it, because when the sea was angry they stayed a long period in our lands. Since then, the gold has been collected from the rivers in special vessels, to later take it to the workshop, where one part is melted in the form of tiles and another, smaller, is left as is to melt the grains little by little.

Very soon, everything that the foreign merchants had taught them, the Mixtec goldsmiths surpassed with their own intelligence: it was they who began to use the resplendent white (dai ñuhu cuisi), the silver, the metal of the Moon, united with the gold, and in this way they managed to work better and were able to make more detailed works using thin and fine gold threads, which they obtained in the same casting of the piece.

The gilding technique, which was also learned from foreign merchants, was applied to tumbaga objects - an alloy containing little gold and a lot of copper - to give them a finish like "fine gold": the object was heated until the copper it formed a layer on the surface, after which the acidic juice of some plants - or also old urine or alum - was applied to remove it. The same finish could be obtained directly with a "gold plating". Unlike foreigners, Mixtec goldsmiths did not use this technique frequently, as they added little copper to their alloys.

When the old goldsmith went to work in the workshop to learn his father's trade, he was very astonished to see how the hammers, using powerful stone mallets and leaning on simple anvils of different shapes, made sheets of varying thickness, as described try to make nose rings, earmuffs, rings, frontal bands or vessels; With the thinnest ones, the charcoal and clay beads were covered, and with the thickest ones they made discs of the solar god, on which, following the instructions of the priests, they made complex symbolic designs with a chisel.

Each of the symbols had its own meaning (the frets, for example, schematic manifestations of the god Koo Sau, evoked the serpent). For this reason, the scrolls, meanders, wavy short lines, spirals, grains and braiding, regardless of the goldsmith center, kept the same features. Mixtec goldsmithing was distinguished by some elements, such as the thin threads that resemble lace –with which, in addition to feathers and flowers, the artists designed the features of the gods– and the sonorous bells that were used to finish off the pieces.

We Mixtecs are very proud of our gold pieces; We have always been the owners of the resplendent yellow, the waste of the Sun God Yaa Yusi, which he himself deposits in our rivers; we are the richest in this metal, and we control it. Goldsmiths are allowed to work with gold, but only nobles, rulers, priests and warriors can use objects made with this metal, because it is considered a sacred matter.

Goldsmiths manufactured emblem jewelry and insignia. The former gave distinction and power to its wearer: earmuffs, necklaces, breastplates, pectorals, bracelets, bracelets, simple hoop-type rings and others with pendant, false nails, plain discs or with embossed motifs and inlays of turquoise and lamellae to be sewn on different garments. The insignia, for their part, indicated high social ranks within the nobles themselves; they were worn according to lineage –such as tiaras, crowns and diadems–, or for military merits –such as nose rings, nose buttons and labia. Through these emblem jewels and insignia, a ruler showed that he was a descendant of the gods; They had given him power, that is why he ruled and his word was law.

The precious gold objects we made first only for our gods, priests, warriors and rulers; later, we began to market them in other major cities, outside our region. But we only sold the items! The knowledge to manufacture a piece is a secret that goldsmiths jealously guard, passing it on from father to son.

First the object was designed with wax; later the mold of coal and clay was made, leaving some "vents" for the air to come out when pouring the molten metal. Then the mold was placed in the bracero, so that the wax would melt and dislodge the cavities that would be occupied by the gold.

The mold must not be removed from the fire, as it must be hot and without traces of moisture or wax at the time of casting the gold; the metal, simultaneously melted in a refractory crucible, we pour it through the mouth of the mold so that it flows through the cavities left by the wax.

The mold had to be allowed to cool slowly in the already extinguished brazier; once completely cold, the mold was broken and the piece was removed; Later, it was subjected to a polishing and cleaning process: the first polishing was to remove the marks from the vents; then an alum bath was applied to the piece and the surface oxides were removed by means of heat; finally, before polishing it again, it was given an acid bath, in order to make the gold more shiny.

We Mixtecs have the knowledge to work metals perfectly: we know how to achieve alloys, how to weld cold and heat, either using filler materials, such as copper and silver crystals, or by melting the two parts to join, without adding other metal; We can also weld metals by hammering. We are so proud of our work when we find that the parts that have been soldered together cannot be distinguished! We know how to forge, stamp, crimp delicate stones and emboss, and we know the right tool to achieve angular or rounded designs.

The goldsmiths achieved such mastery and knowledge of the casting technique that they could use two metals - gold and silver - in the same mold to make very complicated objects: the gold was poured first, because its melting point is higher. high, and then to a certain degree of cooling, but still with the hot mold on the brazier, the silver was emptied.

The rings, in particular those that have a bird figure attached, require a high degree of technical refinement, since, in addition to requiring several molds, all the parts that make up the piece must be melted and welded.

The goldsmiths were supervised by the priests, especially when they had to represent the gods in rings, pendants, brooches and pectorals: Toho Ita, lord of flowers and summer; Koo Sau, the sacred feathered serpent; Iha Mahu, the Flayed One, god of spring and goldsmiths; Yaa Dzandaya, deity of the Underworld; Ñuhu Savi or Dazahui, god of rain and lightning, and Yaa Nikandii, the solar god, implicit in the gold itself. All of them were represented as men, including the Sun, which was also evoked in the form of smooth circles or with embossed solar rays. The divinities had zoomorphic manifestations: jaguars, eagles, pheasants, butterflies, dogs, coyotes, turtles, frogs, snakes, owls, bats and opossums. The scenes of cosmogonic events that were captured in some pieces were also supervised by the priests.

Night had fallen, and the smelting furnace was almost completely cold. The young apprentices had to retire, because the next day, with the first rays of the morning, they had to return to the workshop to become the architects of the Sun.

The old goldsmith glanced around the surroundings and rested his eyes on a die:

One of my first jobs was to polish, with a soft cotton cloth, the polished sheets of metal that are placed in this die.

The year is 1461. The old goldsmith has long since died, as did his attentive listeners. The art of goldsmithing continues to be cultivated with the same mastery, pride and zeal. The Mixtec style has come to prevail thanks to the fact that the goldsmiths know and embody in their works the symbols and deities known and venerated by all the peoples of their environment.

Coixtlahuaca and its tributaries have fallen under Mexica rule; little by little, other Mixtec lordships are also subject to Tenochtitlan; Numerous gold objects arrive at that capital as payment of tributes. In Tenochtitlan you can now find manufactured works both in the Mixtec goldsmith centers and in Azcapotzalco, a city to which the Mexica transferred some Mixtec goldsmith workshops.

Time goes by. It has not been easy to subdue the Mixtecs: Tututepec continues to be the capital of the Mixteca de la Costa; the once city of the mighty ruler 8 Jaguar Claw Deer is the only independent manor of the Mexica domain.

The year 1519 has arrived. The Mixes have sighted some floating houses; other foreigners are coming. Will they bring things to exchange? They wonder. Yes, blue glass beads, for gold pieces.

From the moment Hernán Cortés asked Moctezuma where the gold was, it was clear that it was in Oaxaca. Thus, the metal of the Mexica came into Spanish hands as spoils of war and also through the looting of tombs.

When the conquest was made, the Mixtecs continued to pay their tribute in gold: precious objects whose destination was foundry. The gods, turned into ingots, went to distant lands, where, once more melted and transformed into coins, no one could recognize them. Some of them, those who were buried, try to go unnoticed: silent, they do not emit a single glow. Sheltered by the earth, they wait for their true children to come to light without fear of the crucible. When they emerge, the goldsmiths will tell their story and protect them; The Mixtecs will not let their past die. Their voices are powerful, not in vain they carry with them the power of the Sun.

Source: Passages of History No. 7 Ocho Venado, the Conqueror of the Mixteca / December 2002