Michoacán, the "place where fish abounds," was one of the largest and richest kingdoms in the pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican world; its geography and the extension of its territory gave place to different human settlements, whose footprint has been discovered by specialist archaeologists in western Mexico.

The constant multidisciplinary investigations allow the visitor to offer a more complete vision of the chronology corresponding to the first human settlements and the later ones that formed the legendary Purépecha Kingdom.

Unfortunately, the looting and the lack of multidisciplinary research so necessary in this important region, have not allowed to date to give a complete vision that reveals exactly the chronology corresponding to the first human settlements and that of those later, which were forming the legendary Purépecha Kingdom. The dates that are known with some exactness correspond to a late period, relatively prior to the process of the Conquest, however, thanks to the documents written by the first evangelizers and that we know by the name of "Relationship of ceremonies and rites and population and government of the Indians of the Province of Michoacán ”, it has been possible to reconstruct a gigantic puzzle, a history that allows us to see clearly, from the middle of the 15th century, a culture whose political and social organization became of such magnitude , which was able to keep the almighty Mexica empire at bay.

Some of the difficulties to have a complete understanding of the Michoacan culture reside in the Tarascan language, since it does not correspond to the linguistic families of Mesoamerica; Its origin, according to prestigious researchers, is distantly related to Quechua, one of the two main languages in the South American Andean zone. The kinship would have its starting point approximately four millennia ago, which allows us to immediately reject the possibility that the Tarascans had arrived, coming from the Andean cone at the beginning of the 14th century of our era.

Around 1300 AD, the Tarascans settled in the south of the Zacapu basin and in the Pátzcuaro basin, undergo a series of important transformations in their settlement patterns that indicate the presence of migratory currents that are incorporated into sites already inhabited for a long time. behind. The Nahuas called them Cuaochpanme and also Michhuaque, which means respectively “those with a wide path in the head” (the shaved ones), and the “owners of the fish”. Michuacan was the name that they gave only to the population of Tzintzuntzan.

The ancient Tarascan settlers were farmers and fishermen, and their supreme deity was the goddess Xarátanga, while the migrants who appeared in the 13th century were gatherers and hunters who worshiped Curicaueri. These farmers are an exception in Mesoamerica, due to the use of metal - copper - in their farming instruments. The group of Chichimeca-Uacúsechas hunter gatherers took advantage of the compatibility of the cult that existed between the aforementioned deities to integrate into a period that was transforming their subsistence patterns and their level of political influence, until achieving the foundation of Tzacapu-Hamúcutin-Pátzcuaro , sacred site where Curicaueri was the center of the world.

By the fifteenth century, those who were strange invaders become chief-priests and develop a sedentary culture; power is distributed in three places: Tzintzuntzan, Ihuatzio and Pátzcuaro. A generation later, power is concentrated in the hands of Tzitzipandácure, with the character of the sole and supreme lord that makes Tzintzuntzan the capital of a kingdom, whose extension is calculated at 70 thousand km²; it covered part of the territories of the current states of Colima, Guanajuato, Guerrero, Jalisco, Michoacán, México and Querétaro.

The wealth of the territory was based fundamentally on obtaining salt, fish, obsidian, cotton; metals such as copper, gold, and cinnabar; seashells, fine feathers, green stones, cocoa, wood, wax and honey, whose production was coveted by the Mexica and their powerful tripartite alliance, which originated that from the Tlatoani Axayácatl (1476-1477) and his successors Ahuizotl (1480 ) and Moctezuma II (1517-1518), undertook fierce war campaigns on the indicated dates, tending to subdue the kingdom of Michoacán.

The successive defeats suffered by the Mexicans in these actions have suggested that the Cazonci had a more efficient power than the all-powerful monarchs of Mexico-Tenochtitlan, however when the capital of the Aztec empire fell into the hands of the Spanish, and since those New men had defeated the hated but respected enemy, and alerted by the fate of the Mexican nation, the Purépecha kingdom established a peace treaty with Hernán Cortés to prevent his extermination; Despite this, the last of his monarchs, the unfortunate Tzimtzincha-Tangaxuan II, who when baptized received the name of Francisco, was brutally tormented and assassinated by the president of Mexico's first audience, the fierce and sadly famous Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán .

With the arrival of the second audience designated for New Spain, his illustrious Oidor, the lawyer Vasco de Quiroga, was commissioned in 1533 to remedy the moral and material damage caused in Michoacán until then. Don Vasco, deeply identified with the region and its inhabitants, agreed to change the magistrate's toga for the priestly order and in 1536 he was invested as bishop, implanting for the first time in the world in a real and effective way, the fantasy imagined by Santo Tomás Moro , known by the name of Utopia. Tata Vasco -designation granted by the natives- with the support of Fray Juan de San Miguel and Fray Jacobo Daciano, organized the existing populations, founded hospitals, schools and towns, seeking their best location for them and strengthening the markets as a whole. crafts.

During the colonial period, Michoacán reached an exemplary flourishing in the immense territory it then occupied within New Spain, so its artistic, economic and social development had a direct impact on several of the current states of the federation. The colonial art that flourished in Mexico is so varied and rich that endless volumes have been dedicated that analyze it both in general and in particular; the one that flourished in Michoacán has been disclosed in countless specialized works. Given the nature of disclosure that this “Unknown Mexico” note has, this is a “bird's eye view” that allows us to know the fantastic cultural wealth represented by a few of its many artistic manifestations that emerged during the viceregal period.

In 1643 Fray Alonso de la Rea wrote: "Also (the Tarascans) are those who gave the Body of Christ Our Lord, the most vivid representation that mortals have seen." The worthy friar described in this way the sculptures made based on cane paste, agglutinated with the product of the maceration of the bulbs of an orchid, with whose paste they were fundamentally modeled crucified Christs, of impressive beauty and realism, whose texture and shine gives them the appearance of fine porcelain. Some Christs have survived to this day and are worth knowing. One is in a chapel of the Tancítaro church; another is venerated since the 16th century in Santa Fe de la Laguna; one more is in the Parish of the Island of Janitzio, or the one that is in the Parish of Quiroga, extraordinary for its size.

The Plateresque style in Michoacán has been considered as a true regional school and maintains two currents: an academic and cultured, embodied in large convents and towns such as Morelia, Zacapu, Charo, Cuitzeo, Copándaro and Tzintzuntzan and another, the most abundant, is present in infinity of minor churches, chapels of the mountains and small towns. Among the most notable examples within the first group we can mention the Church of San Agustín and the Convent of San Francisco (today Casa de las Artesanías de Morelia); the facade of the Augustinian convent of Santa Maria Magdalena built in 1550 in the town of Cuitzeo; the upper cloister of the Augustinian convent 1560-1567 in Copándaro; the Franciscan convent of Santa Ana from 1540 in Zacapu; the Augustinian one located in Charo, from 1578 and the Franciscan building from 1597 in Tzintzuntzan, where the open chapel, the cloister and the coffered ceilings stand out. If the Plateresque style left its unmistakable mark, the Baroque did not spare it, although perhaps due to the law of contrasts, the sobriety embodied in the architecture was the antithesis of the overflow of expression in its altars and gleaming altarpieces.

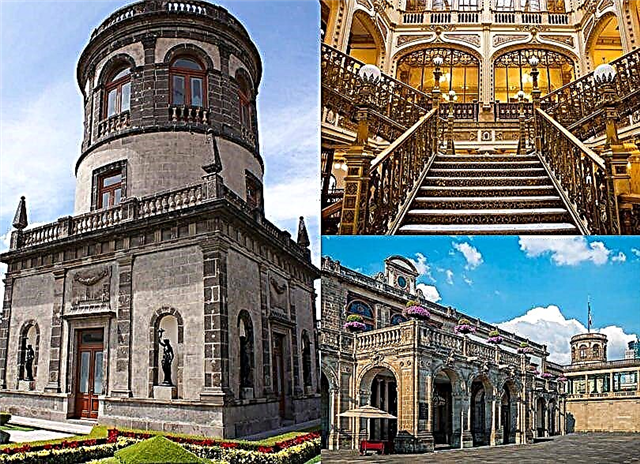

Among the most outstanding examples of the Baroque we find the 1534 cover of “La Huatapera” in Uruapan; the portal of the Angahuan temple; the Colegio de San Nicolás built in 1540 (today the Regional Museum); the church and convent of the Company that were the second Jesuit College of New Spain, in Pátzcuaro, and the beautiful Parish of San Pedro and San Pablo, from 1765 in Tlalpujahua.

The most outstanding examples of the city of Morelia are: the convent of San Agusíin (1566); the church of La Merced (1604); the sanctuary of Guadalupe (1708); the church of the Capuchinas (1737); that of Santa Catarina (1738); La de las Rosas (1777) dedicated to Santa Rosa de Lima and the beautiful Cathedral, whose construction began in 1660. The colonial wealth of Michoacán includes the alfarjes, these roofs are considered the best in all of Hispanic America since they constitute proof evident of the artisan quality developed in the Colony; In them there are basically three functions: an aesthetic, a practical and a didactic; the first for concentrating the main decoration of the temples on the roof; the second, because of their lightness, which in the event of an earthquake would have minor effects, and the third, because they constitute true evangelizing lessons.

The most extraordinary of all these coffered ceilings is preserved in the town of Santiago Tupátaro, painted in tempera in the second half of the 18th century to worship the Holy Lord of Pine. La Asunción Naranja or Naranján, San Pedro Zacán and San Miguel Tonaquillo, are other sites that preserve examples of this exceptional art. Among the expressions of colonial art where the indigenous influence is best represented, we have the so-called atrial crosses that flourished from the 16th century, some were decorated with obsidian inlays, which reiterated in the eyes of the then recently converted, the sacred character of the object. Their proportions and decoration are so varied that experts in colonial art consider them to be sculptures of a “personal” character, a fact that can be seen in those that are unusually signed. Perhaps the most beautiful examples of these crosses are preserved in Huandacareo, Tarecuato, Uruapan and San José Taximaroa, today Ciudad Hidalgo.

To this beautiful expression of syncretic art we must also add the baptismal fonts, true monuments of sacred art that have their best expression in those of Santa Fe de la Laguna, Tatzicuaro, San Nicolás Obispo and Ciudad Hidalgo. With the meeting of two worlds, the 16th century left its indelible mark on the subjugated cultures, but that painful gestation process was the beginning of the birth of the richest and most splendid viceroyalty of America, whose cultural syncretism not only filled its works of art. immense territory, but it was the foundation for the development of the events that arose in our troubled nineteenth century. With the expulsion of the Jesuits, decreed by Carlos III of Spain in 1767, the political conditions of the overseas dominions began to undergo changes that evidenced their discomfort at the actions undertaken by the Metropolis, however it was the Napoleonic invasion of the Iberian Peninsula , which originated the first signs of independence that had their origin in the city of Valladolid -now Morelia-, and 43 years later, on October 19, 1810, it was the headquarters for the proclamation of the abolition of slavery.

In this dramatic episode in our history, the names of José Maria Morelos y Pavón, Ignacio López Rayón, Mariano Matamoros and Agustín de Iturbide, illustrious sons of the bishopric of Michoacán, left their mark, thanks to their sacrifice. the desired freedom was achieved. Once this was consummated, the newborn country would have to face the devastating events that would ensue 26 years later. The period of the Reform and consolidation of the Republic once again inscribed among the heroes of the country the names of illustrious Michoacanos: Melchor Ocampo, Santos Degollado and Epitacio Huerta, remembered to this day for their outstanding actions.

Starting in the second half of the last century and the first decade of the present, the state of Michoacán is the cradle of important figures, determining factors in the consolidation of modern Mexico: scientists, humanists, diplomats, politicians, military men, artists and even a prelate whose canonization process is in force in the Holy See. An impressive list of those who, having been born in Michoacán, have contributed significantly to the aggrandizement and consolidation of the homeland.