Who could deny that Hugo Brehme's photographs deal with very Mexican themes? In them the national landscape is shown in its volcanoes and plains; the architecture in the archaeological remains and colonial cities; and the people, in the charros, Chinese poblanas and Indians in white clothes.

2004 marks the 50th anniversary of Hugo Brehme, the author of these images. Although of German origin, he made his photographic production in Mexico, where he lived from 1906 until his death in 1954. Today he occupies an important place in the history of our photography for his contributions to the movement called Pictorialism, so discredited and almost forgotten for a long time. , but that is revaluing in our days.

From the photographs, which go from San Luis Potosí to Quintana Roo, we know that Brehme traveled almost the entire national territory. He began to publish his photos in the first decade of the 20th century, in El Mundo Ilustrado and other renowned weeklies in the Mexico of those days. He also started selling popular photographic postcards around the second decade and by 1917 National Geographic requested material to illustrate their magazine. In the 1920s, he published the book Mexico Picturesque in three languages, something then unique for a photographic book that contained a great project to disseminate his adopted country, but which in the first instance assured him the economic stability of his photography business. He received one of the awards at the Exhibition of Mexican Photographers in 1928. The following decade coincided with his consolidation as a photographer and the appearance of his images on Mapa. Tourism Magazine, a guide that invited the driver to become a traveler and venture through the roads of the Mexican province. Likewise, the influence he had on later photographers, among them Manuel Álvarez Bravo, is known.

LANDSCAPE AND ROMANTICISM

More than half of the photographic production that we know of Brehme today is dedicated to landscape, the romantic type that captures large areas of land and sky, heir to the nineteenth-century pictorial repertoire, and that shows the majestic nature, especially of the highlands, which it stands imposing and proud.

When a human being appears in these scenes, we see him diminished by the enormous proportion of a waterfall or when contemplating the magnitude of the mountain peaks.

The landscape also serves as a framework to record the archaeological remains and colonial monuments, as witnesses of a past that seems glorious and always exalted by the lens of the photographer.

REPRESENTATIONS OR STEREOTYPES

The portrait was a minor part of his production and took the majority in the Mexican province; More than true portraits, they constitute representations or stereotypes. For their part, the children who appear are always from rural areas and are present as residues of the ancient national civilization, which survived until that moment. Scenes of peaceful life, where they carried out activities considered even today to be typical of their habitat, such as carrying water, herding livestock or washing clothes; nothing different from what C.B. Waite and W. Scott, photographers who preceded him, whose images of indigenous people portrayed in situ were aptly expressed.

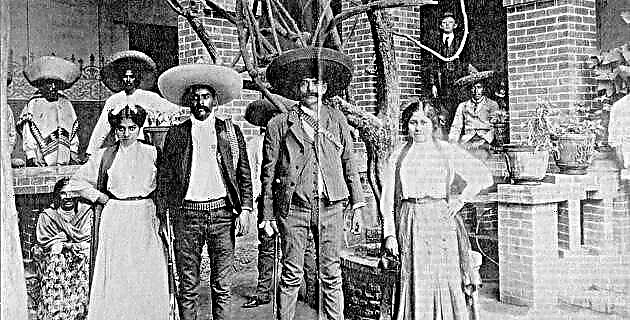

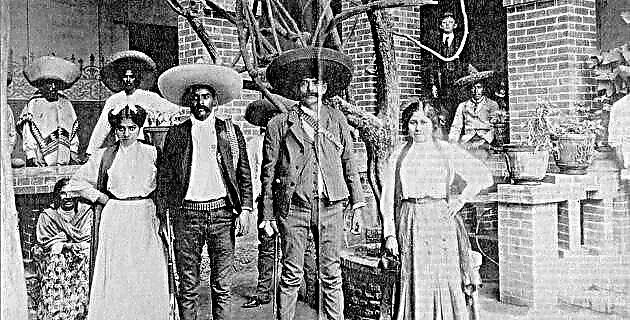

In Brehme, men and women, alone or in groups, appear more often than not portrayed in outdoor spaces and with some element considered typically Mexican such as cactus, nopal, a colonial fountain or a horse. The indigenous and mestizos appear to us as vendors in the markets, shepherds or pedestrians who roam the streets of the towns and cities of the province, but the most interesting are the mestizos who proudly wear the charro costume.

SOMETHING TYPICAL OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

The women almost always appear dressed as poblano Chinese. Today almost no one knows that the “poblana” costume, as Madame Calderón de la Barca called it in 1840, had a negative connotation in the 19th century, when it was considered typical of women of “doubtful reputation”. By the twentieth century, the Chinese from Puebla became symbols of national identity, so much so that in Brehme's photographs they represent the Mexican nation, both picturesque and seductive.

The costumes of china poblana and charro are part of the "typical" of the twentieth century, of what we tend to qualify as "the Mexican" and even in primary schools their use has become an obligatory reference for the dances of children's festivals . The antecedents go back to the 19th century, but it is taken up again during the 20s and 30s when identity was sought in pre-Hispanic and colonial roots, and above all, in the fusion of both cultures, to exalt the mestizo, of which it would be representative the china poblana.

NATIONAL SYMBOLS

If we look at the photograph entitled Amorous Colloquium, we will see a mestizo couple surrounded by the elements that since the second decade of the last century are valued as Mexican. He is a charro, who does not lack a mustache, with a dominant but flattering attitude towards the woman, who wears the famous costume, she perched on a cactus. But, no matter how much praise they receive, who spontaneously chooses to climb or lean on a cactus? How many times have we seen this scene or a similar one? Perhaps in films, advertising and photographs that were building this vision of "the Mexican", which today is part of our imagination.

If we return to photography, we will find other elements that reinforce the construction of the image despite not agreeing with everyday life, both rural and urban: the headband of the woman, in the fashion of the 20s and that seems to support the false braids that have not finished weaving; some suede shoes ?; the making of the pants and boots of the supposed charro ... and so we could continue.

A GOLDEN AGE

Undoubtedly, among our memories we have some black and white image of a charro from the Mexican golden film era, as well as the scenes in outdoor locations where we recognize Brehme's landscapes in motion, captured by Gabriel Figueroa's lens for a good number of tapes that were in charge of reinforcing the national identity inside and outside the Mexican territory, and that had antecedents in photographs like these.

We can conclude that Hugo Brehme photographed in the first three decades of the 20th century more than a hundred archetypal images today, which continue to be recognized at the popular level as representative of “the Mexican”. All of them correspond to the Suave Patria, by Ramón López Velarde, which in 1921 began by exclaiming I will say with a muted epic, the homeland is impeccable and diamond ...

Source: Unknown Mexico No. 329 / July 2004