Trip to the mountain, refuge among mesquites, petition to the grandparents and offerings to the Guadalupana. From the semi-desert to the forest, the flowers mix in the syncretism of the Otomí people who fight to maintain their identity.

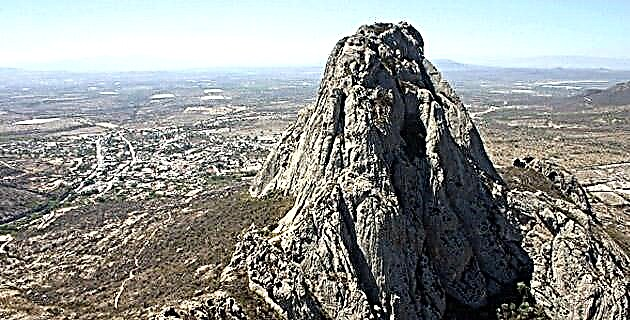

The smell of a homemade stove filled the air as Dona Josefina placed a plate of nopales and beans on the table. Above the hamlet, the silhouette of the Cerrito Parado was drawn with the glow of the moon and the semi-desert could be seen on the dark horizon. It seemed like a scene taken from daily life in the Mesoamerican pre-Hispanic towns that came to life in this Otomí region of Higueras in Tolimán, Querétaro, from where the annual four-day trek to Cerro del Zamorano would begin.

The next morning, very early, the donkeys that would carry our luggage were ready and we started on our way to the community of Mesa de Ramírez, where the chapel that jealously guards one of the two Holy Crosses that make the journey is located. At the head of this community was Don Guadalupe Luna and his son Félix. According to the anthropologist Abel Piña Perusquia, who has studied the region for eight years, the sacred walk and religious activities around the Holy Cross are a form of regional cohesion, since the religious leaders of the twelve communities that make up the Higueras region they attend every year.

After a ceremony presided over by the butler in charge of the cross, the line of pilgrims began to climb the arid and winding roads. They carry in their hands the offerings of desert flowers wrapped in maguey leaves and the necessary food for the trip, without missing the flutes and drums of the musicians.

Upon reaching the end of the "valley", the line of the Maguey Manso community made its appearance at the top and, after a short presentation between crosses and mayordomos, the path was resumed. By then the group was made up of about a hundred people who wanted to offer to the Virgin of the chapel located at the top of the mountain. Minutes later we arrive at an open chapel where the first of seven stops is made, there the crosses with the offerings are placed, copal is lit and prayers are pronounced to the four cardinal points.

During the journey, Don Cipriano Pérez Pérez, butler of the Maguey Manso community, told me that in 1750, during a battle in the Pinal del Zamorano, an ancestor of his entrusted himself to God, who replied: “… if you venerate me, no worry that I am going to save you. " And so it happened. Since then, generation after generation, the family of Don Cipriano has led the pilgrimage: "... this is love, you have to be patient ... my son Eligio is the one who will stay when I am gone ..."

The environment begins to transform as we move forward. Now we walk next to the low forest vegetation and suddenly Don Alejandro stops the long caravan. Children and young people who are attending for the first time must cut some branches and go forward to sweep the site where the second stop will be made. At the end of cleaning the place, the pilgrims enter who, forming two lines, begin to circle in opposite directions around a small stone altar. Finally the crosses are placed under a mesquite. The smoke of the copal mixes with the murmur of the prayers and the sweat is confused with the tears that flow from men and women. Prayer to the four winds is performed once again and the emotional moment culminates with the lighting of copal in front of the Holy Crosses. It is time to eat and each family gathers in groups to enjoy: beans, nopales and tortillas. Shortly after continuing on the road, zigzagging through the hills, the weather turns cold, the trees grow and a deer crosses in the distance.

When the shadows stretch we arrive at another chapel located in front of a large mesquite where we camped. Throughout the night the prayers and the sound of the flute and the tambourine do not rest. Before the sun rises, the crew with the luggage is on its way. Deep in the pine-oak forest and going down a wooded ravine and crossing a small stream, the sound of the bell spreads in the distance. Don Cipriano and Don Alejandro stop and the pilgrims settle down to rest. From afar they give me a discreet signal and I follow them. They enter a path among the vegetation and disappear from my sight to reappear under a huge rock. Don Alejandro lit some candles and placed some flowers. At the end of the ceremony in which only four people participated, he told me: "we come to offer to the so-called grandparents ... if someone is sick, they are asked and then the sick person gets up ..."

The Chichimeco-Jonaces "grandparents" who inhabited the region mixed with the Otomi groups that accompanied the Spanish in their forays into the area in the seventeenth century, which is why they are considered ancestors of the current inhabitants.

After one hill another followed and another. As he turned one of the many curves in the path, a boy crouched in a mesquite tree began to count the pilgrims until he reached 199, a number that he recorded on the tree. "In this place people are always told.", He told me, "... it has always been done ..."

Before the sun went down, the bell rang again. Once again the young men came forward to sweep the site where we would camp. When I arrived at the place I was presented with a huge rocky shelter, a cavity 15 meters high by 40 meters wide, which faces north, towards Tierra Blanca, in Guanajuato. In the background, at the top of the rock face, were barely visible images of a Virgin of Guadalupe and a Juan Diego, and beyond, even less perceptible, the Three Wise Men.

On the path that runs along the side of the wooded mountain, the pilgrims advanced on their knees, slowly and painfully due to the stony terrain. The crosses were placed under the images and the customary prayers were performed. The vigil shocked me when the lighting of the candles and the fireplaces trickled down the walls and the echo answered the prayers.

The next morning, a little numb from the cold that comes from the north of the mountain, we returned along the path to find the heavy path that climbs to the top. On the north side, a small chapel made of stones superimposed on a large rock awaited the Holy Crosses, which were placed under the image of another Virgin of Guadalupe embodied on the monolith. Felix and Don Cipriano began the ceremony. The copal immediately filled the small enclosure and all the offerings were deposited at their destination. With a mixture of Otomí and Spanish, he thanked himself for having arrived safely, and the prayers flowed along with the tears. The thanks, the sins expiated, the requests for water for the crops had been given.

The return was missing. Plants would be cut from the forest to offer them in the semi-desert and at the beginning of the descent from the mountain the raindrops began to fall, a rain that had been needed for months. Apparently the grandparents of the mountain were happy to have been offered.