On the scattered and sad hamlet of Huey-Colhuacan, at the confluence of the Tamazula and Humaya rivers, the cruel, grim and avaricious Spanish adventurer Nuño de Guzmán founded the Villa de San Miguel de Culiacán, on September 29, 1531, thus culminating the brief but bloody conquest of the Sinaloan territory.

On the scattered and sad hamlet of Huey-Colhuacan, at the confluence of the Tamazula and Humaya rivers, the cruel, grim and avaricious Spanish adventurer Nuño de Guzmán founded the Villa de San Miguel de Culiacán, on September 29, 1531, thus culminating the brief but bloody conquest of the Sinaloan territory.

Nuño de Guzmán handed over encomiendas to his soldiers and thereby tried to root them, but an indigenous rebellion led by Ayapin made the process difficult. Finally this rebellion was crushed in the manner of Guzmán: by blood and fire, and Ayapin was dismembered in a makeshift pillory installed in the center of the nascent town.

However, the indigenous movement resurfaced almost immediately, causing Spanish families to flee to Santiago de Compostela, Nayarit, Guadalajara, Mexico City and some to Peru. On the other hand, the new colonists had no vocation as farmers and left their encomiendas in the hands of their trusted mayordomos. Thus, despite thousands of shocks and anguish, the Villa de San Miguel de Culiacán grew and the first signs of its development were the construction of a small parish, a parade ground and a house for the council. The descendants of the first formally settled Spaniards, that is, the first Culiacan Creoles, carried the surnames Bastidas, Tapia, Cebreros, Arroyo, Mejía, Quintanilla, Baeza, Garzón, Soto, Álvarez, López, Damián, Dávila, Gámez, Tolosa, Zazueta, Armenta, Maldonado, Palazuelos, Delgado, Yáñez, Tovar, Medina, Pérez, Nájera, Sánchez, Cordero, Hernández, Peña, Amézquita, Amarillas, Astorga, Avendaño, Borboa, Carrillo, De la Vega, Castro, Collantes, Quintero, Ruiz, Salazar, Sáinz, Uriarte, Verduzco and Zevada, which subsist to this day.

The Villa de San Miguel de Culiacán served as an inn and post on the long journey from Alamos to Guadalajara, and later became the political center of Sinaloa, while Mazatlán became the commercial center par excellence.

The greatest splendor of the town was caused by the exploitation of the royal gold and silver mines, and it even had its own mint and was the first town in the northwest that had a telegraph, then electricity and finally piped water and a system of sewer system.

When the mining decline occurred, after a ruthless overexploitation of natural resources nestled mainly in the depths of the ravines of the Sierra Madre Occidental, agriculture gained vigor, especially on the banks of rivers and streams (we must not forget that Sinaloa it is a pluvial state, with 11 rivers and more than 200 streams).

The history of the Villa de San Miguel de Culiacán has been extremely agitated by the violence of barracks, rebellions and civil wars that kept the land in suspense. For example, it was the point of the advance of the Spanish militias to the North, and from here left in the 16th century the Franciscan friar Marco de Niza, who in his delirium believed he had found the golden city of Cíbola, and Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, who extended the territory of New Spain to the Colorado Canyon.

The town was also the host of a strange and fascinating character who would later gain universal fame: Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca. Cabeza de Vaca survived the wreck of Pánfilo de Narváez's fleet off the coast of Florida. He spent eight years on an erratic wandering from Florida to Sinaloa. He ran into Spanish militias in Bamoa, on the banks of the Petatlán River (Sinaloa), and on April 1, 1536, the mayor of the town, Melchor Díaz, named him guest of honor. He had traveled 10,000 kilometers in the crossing of Texas, Tamaulipas, Coahuila, New Mexico, Arizona, Chihuahua, Sonora and finally Sinaloa.

Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca continued the trip to the capital of New Spain, where he gave a comprehensive report to Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza on the wealth of gold and silver in the vast territory he crossed. It was, of course, another fantasy-filled description, much like that of the Friar Marco de Nice, which, of course, provoked the viceroy's natural greed.

After long revolts, when the military governors were in power for only a few months, Sinaloa had a dictator, General Francisco Cañedo, who calmed down political hatred with the force conferred on him by the President of the Republic, Porfirio Díaz. It was a dictatorship that lasted more than 30 years, until the Mexican Revolution was unleashed.

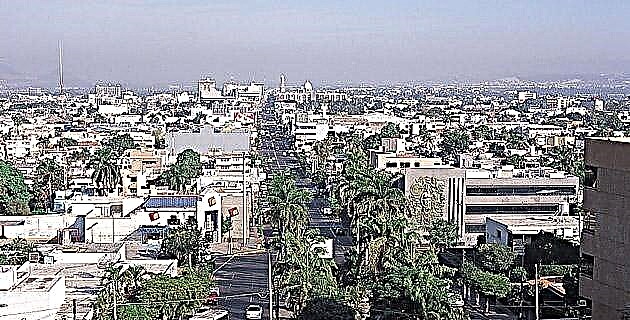

As soon as the Revolution subsided, an attempt was made to take advantage of the hydraulic possibilities of the Sinaloan rivers. In 1925 the Rosales canal was built, and 22 years later the first great hydraulic work in the northwest was completed, a pioneer of high irrigation: the Sanalona dam on the Tamazula river, which was inaugurated on April 2, 1948 and was the detonator of an economy that continues to find its main support in agriculture. Due to the enormous agricultural boom, Culiacán went from the 30,000 inhabitants it had in 1948 to 100,000 in ten years. The old Villa de San Miguel de Culiacán was no longer the muleteers' inn, but a great city that today has everything — land, water, men — to be the great metropolis of the 21st century.

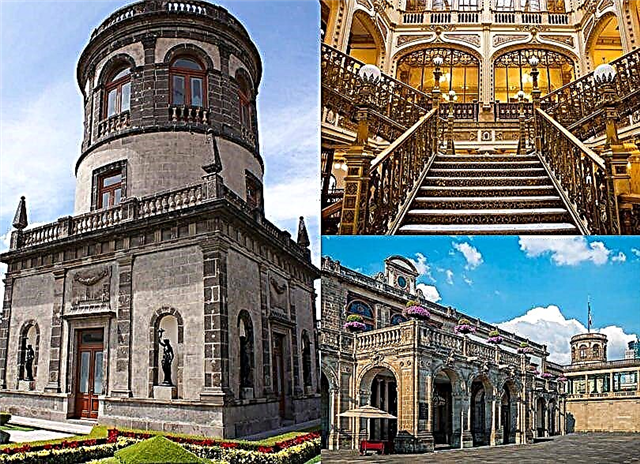

The Historic Center of Culiacán

Perhaps there is nothing more eloquent than a house or a building to tell us about a time, or about the culture of those who built or lived in them. When walking through the streets of the Center, admiring the domes of the Temple of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and the Cathedral; peering into their houses with patios surrounded by arcades, or watching the sunset sitting on a bench in Plazuela Rosales, we vividly feel the greatness and warmth of its people.

Source: Aeroméxico Tips No. 15 Sinaloa / Spring 2000