Their roars emerged from the long night of time, which must have astonished and frightened more than one. His strength, his agility, his stained skin, his stealth and dangerous stalking through the Mesoamerican jungles, must have instilled in the primitive peoples the belief in a deity, in a sacred entity that had to do with telluric forces and fertility. of the nature.

The Olmecs, whose enigmatic presence in Guerrero has not yet been fully clarified, reflected it in cave paintings, monoliths and in multiple ceramic and stone representations. His mythical character is projected to this day, when his figure is recreated in one of the most abundant masquerade productions in the country, in dances, in agricultural ceremonies in some towns, in the La Montaña region, in the places of various names. peoples, in traditions and legends. The jaguar (panther onca) has thus, with the passing of time, become an emblematic sign of the people of Guerrero.

THE OLMEC ANTECEDENTS

A millennium before our era, for the same period in which the so-called mother culture flourished in the metropolitan area (Veracruz and Tabasco), the same happened in Guerrero lands. The discovery, three decades ago, of the site of Teopantecuanitlan (Place of the temple of the tigers), in the municipality of Copalillo, confirmed the dating and periodicity that was already attributed to the Olmec presence in Guerrero, based on the findings previous two sites with cave paintings: the Juxtlahuaca cave in the municipality of Mochitlán, and the cave of Oxtotitlan in the municipality of Chilapa. In all these places the presence of the jaguar is conspicuous. In the first, four large monoliths have the typical tabby features of the most refined Olmec style; In the two sites with cave painting we find several manifestations of the figure of the jaguar. In Juxtlahuaca, in a place located 1,200 m from the entrance to the cave, a jaguar figure is painted that appears associated with another entity of great significance in the Mesoamerican cosmogony: the serpent. In another place within the same enclosure, a large character dressed in jaguar skin on his hands, forearms and legs, as well as in his cape and what appears to be the loincloth, appears erect, imposing, before another person kneeling in front of him.

In Oxtotitlan, the main figure, representing a great personage, is seated on a throne in the shape of the mouth of a tiger or monster of the earth, in an association that suggests the linking of the ruling or priestly caste with the mythical, sacred entities. For archaeologist David Grove, who reported these remains, the scene depicted there seems to have an iconographic meaning related to rain, water, and fertility. Also the so-called figure l-D, within the same site, has singular importance in the iconography of this pre-Hispanic group: a character with typically Olmec features, standing, stands behind a jaguar, in the possible representation of a copula. This painting suggests, according to the aforementioned author, the idea of a sexual union between man and jaguar, in a profound allegory of the mythical origins of that people.

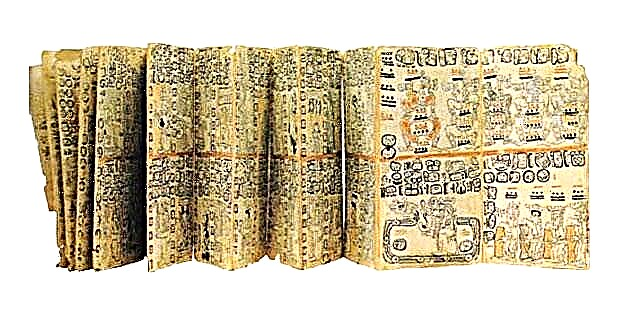

THE JAGUAR IN THE CODEXES

From these early antecedents, the presence of the jaguar continued in multiple lapidary figurines, of uncertain provenance, which led Miguel Covarrubias to propose Guerrero as one of the Olmec origin sites. Another of the important historical moments in which the figure of the jaguar has been captured has been in the early colonial period, within the codices (pictographic documents in which the history and culture of many of the current Guerrero peoples were recorded). One of the earliest references is the figure of the tiger warrior that appears on Canvas 1 of Chiepetlan, where scenes of combat between the Tlapaneca and the Mexica can be observed, which preceded their domination of the Tlapa-Tlachinollan region. Also within this group of codices, number V, of colonial manufacture (1696), contains a heraldic motif, copied from an official Spanish document, with the representation of two lions. The reinterpretation of the tlacuilo (the one that paints the codices) reflected two jaguars, since tigers were not known in America, in a clear indigenous style.

On folio 26 of the Azoyú Codex 1 an individual with a jaguar mask appears, devouring another subject. The scene appears associated with the enthronement of Mr. Turquoise Serpent, in the year 1477.

Another group of codices, from Cualac, reported by Florencia Jacobs Müller in 1958, was produced at the end of the 16th century. In the center of plate 4 we find a couple. The male carries a command staff and is sitting on a cave, which has the figure of an animal, a feline, associated with it. According to the researcher, it is about the representation of the place of origin of the Cototolapan manor. As is common within a Mesoamerican tradition, we find there the association of cave-jaguar-origins elements. At the bottom of the general scene in that document appear two jaguars. In the Lienzo de Aztatepec and Zitlaltepeco Codex de las Vejaciones, in its upper left portion the motifs of the jaguar and the serpent appear. In the late Santiago Zapotitlan Map (18th century, based on an original from 1537), a jaguar appears in the configuration of the Tecuantepec glyph.

DANCES, MASKS and TEPONAXTLE

As a result of these historical-cultural antecedents, the figure of the jaguar is gradually amalgamating and confusing with that of the tiger, which is why its various manifestations are now named after this feline, even when the image of the jaguar underlies the background. Today, in Guerrero, within the multiple expressions of folklore and culture in which the feline manifests itself, the persistence of dance forms in which the presence of the tiger is still evident, is an indicator of this roots.

The dance of the tecuani (tiger) is practiced in almost all the geography of the state, acquiring some local and regional modalities. The one practiced in the La Montaña region is called the Coatetelco variant. It also receives the name of "Tlacololeros". The plot of this dance occurs in the context of livestock, which must have taken root in Guerrero in colonial times. The tiger-jaguar appears as a dangerous animal that can decimate livestock, for which Salvador or Salvadorche, the landowner, entrusts his assistant, Mayeso, with hunting the beast. Since he cannot kill her, other characters come to her aid (the old flechero, the old lancer, the old cacahi, and the old xohuaxclero). When these also fail, Mayeso calls the old man (with his good dogs, among which is the Maravilla dog) and Juan Tirador, who brings his good weapons. Finally they manage to kill him, thereby averting the danger to the farmer's animals.

In this plot, a metaphor for Spanish colonization and the subjugation of indigenous groups can be seen, since the tecuani represents the “wild” powers of the conquered, who threaten one of the many economic activities that were the privilege of the conquerors. When consummating the death of the feline the domination of the Spanish over the indigenous is reaffirmed.

Within the extensive geographical scope of this dance, we will say that in Apango the whips or chirriones of the tlacoleros are different from those of other populations. In Chichihualco, their clothing is somewhat different and the hats are covered with zempalxóchitl. In Quechultenango the dance is called "Capoteros". In Chialapa he received the name "Zoyacapoteros", alluding to the zoyate blankets with which the peasants covered themselves from the rain. In Apaxtla de Castrejón “the Tecuán dance is dangerous and daring because it involves passing a rope, like a circus tightrope walker and at great height. It is the Tecuán that crosses vines and trees as if it were a tiger that returns with a belly full of the cattle of Salvadochi, the rich man of the tribe ”(So we are, year 3, no. 62, IV / 15/1994).

In Coatepec de los Costales the variant called Iguala is danced. On the Costa Chica, a similar dance is danced among the Amuzgo and mestizo peoples, where the tecuani also participates. This is the dance called "Tlaminques". In it, the tiger climbs the trees, palm trees and the church tower (as also happens in the Teopancalaquis festival, in Zitlala). There are other dances where the jaguar appears, among which are the dance of the Tejorones, a native of the Costa Chica, and the dance of the Maizos.

Associated with the tiger dance and other folkloric expressions of the tecuani, there was a masquerade production among the most abundant in the country (along with Michoacán). Currently an ornamental production has been developed, in which the feline continues to be one of the recurring motifs. Another interesting expression associated with the figure of the tiger is the use of the teponaxtli as an instrument that accompanies processions, rituals, and correlated events. In the towns of Zitlala, head of the municipality of the same name, and Ayahualulco -of the municipality of Chilapa- the instrument has a tiger face carved on one of its ends, which reaffirms the symbolic role of the tiger-jaguar in events relevant within the ritual or festive cycle.

THE TIGER IN AGRICULTURAL RITES

La Tigrada in Chilapa

Even when it is carried out within the period in which assurance or fertility rites begin to be performed for the harvest (first fortnight of August), the tigrada does not appear closely linked to the agricultural ritual, although it is possible that in its origins it was. It ends on the 15th, the day of the Virgin of the Assumption, which was the patron saint of Chilapa during part of the colonial period (the town was originally called Santa María de la Asunción Chilapa). La tigrada has been going on for a long time, so much so that the older people of Chilapa already knew it in their youth. It will be a decade since the custom began to decline, but thanks to the interest and promotion of a group of enthusiastic chilapeños interested in preserving their traditions, the tigrada has gained new vigor. The tigrada begins at the end of July and lasts until August 15, when the festival of the Virgen de la Asunción takes place. The event consists of groups of young and old, dressed as tigers, wandering in herds through the main streets of the town, hesitating the girls and scaring the children. As they pass they emit a guttural roar. The conjunction of several tigers in a group, the strength of their dress and their masks, to which is added their bellow and that, at times, they drag a heavy chain, has to be imposing enough for many children to literally panic. before his step. The older ones, complacently, only take them on their lap or try to tell them that they are locals in disguise, but the explanation does not convince the little ones, who try to flee. It seems that the confrontation with the tigers is a difficult trance that all children from Chilapeño have gone through. Already grown up or emboldened, the kids “fight” the tigers, making a hoot with their hand in their mouths and provoking them, prodding them, by shouting: “Yellow tiger, skunk face”; "Meek tiger, chickpea face"; "Tiger without a tail, face of your aunt Bartola"; "That tiger does nothing, that tiger does nothing." The tiger is reaching its climax as the 15th approaches. In the warm afternoons of August gangs of tigers can be seen running through the streets of the town, chasing the young people, who run wildly, fleeing from them. Today, on August 15 there is a procession with allegorical cars (dressed cars, the local people call them), with representations of the Virgin of the Assumption and with the presence of groups of tigers (tecuanis) coming from neighboring towns, to try to exhibit before the population a range of the various expressions of the tecuani (the tigers of Zitlala, Quechultenango, etc.).

A form similar to the tiger is the one that takes place during the patronal feast in Olinalá on October 4. The tigers go out into the streets to chase boys and girls. One of the main events is the procession, in which the Olinaltecos carry offerings or arrangements where the products of the harvest stand out (chiles, especially). The tiger mask in Olinalá is different from that of Chilapa, and this, in turn, is different from that of Zitlala, or Acatlán. It can be said that each region or town imprints a particular stamp on its feline masks, which is not without iconographic implications regarding the reason for these differences.

Source: Unknown Mexico No. 272 / October 1999