The colonial era motivated Spanish writers to take an interest in New Spain. Find out more about the literature of this time ...

As the Colony progressed, more specifically the Baroque period, the two Spains, the Old and the New, tended to resemble each other more, but there were great contrasts between them. Many Spanish writers wanted to come to the new lands: Cervantes himself requested in vain various positions in the overseas kingdoms, the very high mystic Saint John of the Cross was already preparing his departure when death closed his way, and other writers, such as Juan de la Cueva, Tirso de Molina and the ingenious Eugenio de Salazar spent some years in the new lands.

Sometimes an artist added his permanent presence to the influence that his works exerted on the baroque culture of the New World, however the literary expression of New Spain has insurmountable exponents in Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Bernardo de Balbuena, Juan Ruiz de Alarcón, Francisco Bramón, Miguel de Guevara -Michoacan who is credited with the famous sonnet "My God does not move me to love you", which is neither from San Juan de la Cruz, nor from Santa Teresa- and even Fray Juan de Torquemada.

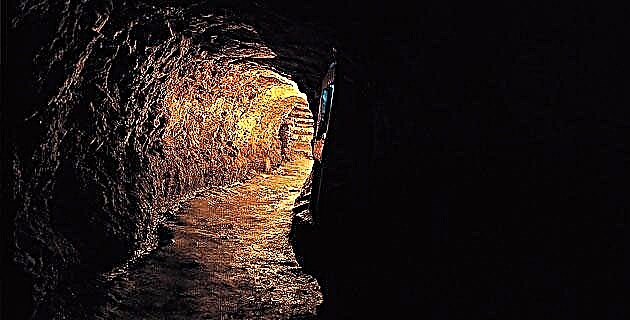

Speaking of literary baroque we can make some considerations: Perhaps the most pronounced feature of literary baroque is, perhaps, the contrast. This chiaroscuro, which in the works manifests itself as a paradox, contradiction and use of thesis and antithesis, is almost an unequivocal symptom of the baroque use of language: let us think, for example, of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz's sonnet: “al That ungrateful leaves me looking for a lover, / the lover who follows me I leave ungrateful / I constantly adore whom my love mistreats; / mistreatment whom my love constantly seeks ”, in it, both the theme and the words used are an absolute demonstration of the one and its opposite. The writer does not claim originality, a concept that neither in the Renaissance nor the Baroque matters as today, but on the contrary, the notion demímesisoimitatio, which in clear Spanish is “to resemble, to imitate the manners or the gestures”, was many times what gave the writer his good invoice and reputation. This guaranteed the erudition and the prestige of the one who wrote a work. In general, the chronicler expresses his sources and highlights the authors who influence him. They usually establish the analogy, to insert their own within a universal context. For example, Sor Juana follows the conventional guidelines of the traditional baroque analogical code: when it comes to paying homage to someone, for example in the case of the Allegorical Neptune, she equates him to a classical deity. Lyric was the most popular genre of the time, and among her the sonnet has a special place. Other genres were also cultivated, of course: the chronicle and the theater, the dissertation and the sacred letters and other works of minor art. Baroque poets, with their tricks, use the paradoxical, the antithetical, the contradictory, the exaggerated, the mythological, literary impact, tremendous effects, surprising descriptions, exaggeration. They also make literary games and quirks like anagrams, emblems, mazes, and symbols. The taste for exaggeration leads to artifice or, baroquely we would say, vice versa.The themes can vary but in general they speak of the contrasts between feeling and reason, wisdom and ignorance, heaven and hell, passion and calm, temporality, the vanity of life , the apparent and the true, the divine in all its forms, the mythological, the historical, the scholarly, the moral, the philosophical, the satirical. There is a culteran emphasis and a pronounced taste for rhetoric.

The realization that the world is a representation, a masquerade, is one of the triumphs of the Baroque inside and outside of literature.