The closed of Santa Teresa # 1 boils animation. In the midst of that bustle and that of the street vendors, the shout of a shouter comes out: "The execution of Captain Cootaaaa ..., the horrible son who killed his horrible maadreeee ..."

The closed of Santa Teresa # 1, where is the printing of Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, boils animation. In the midst of this bustle and that of the street vendors, the shout of a shouter comes out, who emerging hastily through the door of the printing house with a newspaper in his hand, proclaims with a stentorian voice: “the shooting of Captain Cootaaaa…., the horrible son who killed his horrible maadreeee ... "

Within this activity, he contrasts the stillness of a child who has left his books on the floor and watches fascinated from the street through his own mist on the glass of the printing press window, the running of a burin on the burnished plate metal, masterful mint handled by the hand of José Guadalupe Posada. The boy, José Clemente Orozco, does not blink, and through his eyes that actively follow the stroke of the burin, he also etches his future in his mind.

Outside was the marvelous engraver Posada of the childlike presence of José Clemente, and of what his example would achieve; he only noticed a small hand, hurriedly stealthy, picking up the shavings dislodged by the burin from the ground.

Posada is the creator who most influenced Mexican artists in the first half of this century. The painters José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Francisco Gotilla and Guillermo Meza received their inheritance, as well as the engravers Francisco Díaz de León, Leopoldo Méndez, Alfredo Zalce, Francisco Moreno Capdevila, Arturo García Bustos, Adolfo Mexiac and Alberto Beltrán . The Taller de grafica Popular, founded in 1937, is the historic Posada heir.

From being considered a popular artisan, José Guadalupe Posada reached one of the most prominent positions as an artist, because he began and inspired the most brilliant era of national art in the present century: the Mexican School of Painting.

Disregarding European art, and even national art, totally freed him from commitments; in his original engravings he always showed complete freedom.

I never reach vain virtuosity: direct expression was his only concern because he lived absorbed in the things of Mexico.

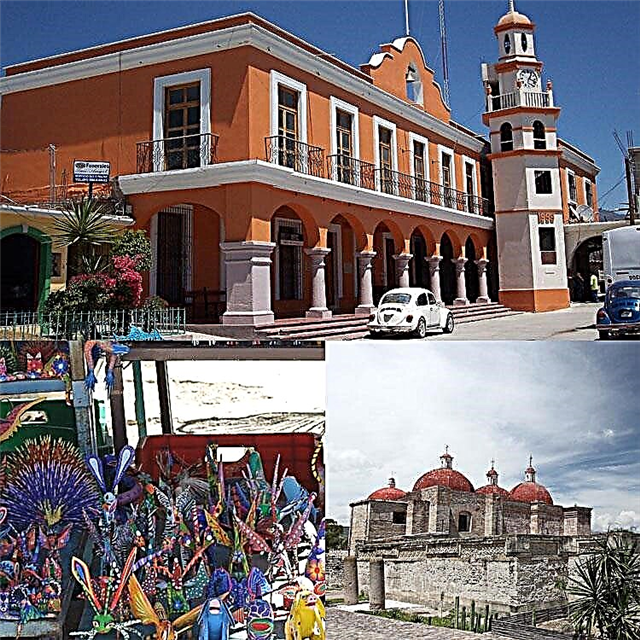

José Guadalupe Posada Aguilar was born at ten o'clock at night on February 2, 1852 on an unnamed street in the San Marcos neighborhood in the city of Aguascalientes; He was the son of German Posada, a baker by trade, married to Petra Aguilar. At the age of 12 he entered the Aguascalientes Academy of Arts and Crafts to study painting and at 18 he was already an apprentice in the Trinidad Pedrosa workshop, where he learned to work with lithography, in addition to engraving in bronze and wood.

Politically persecuted by the chief Jesús Gómez because of the sarcasm of his publications and cartoons, in 1872 Pedroso and Posada marched to the city of León where they founded a new printing press.

In 1875 Posada married María de Jesús Vela and in 1876 he bought Pedrosa's printing press at a price of less than one hundred pesos; There he illustrated books and printed religious images and posters, in keeping with the romanticism of that time.

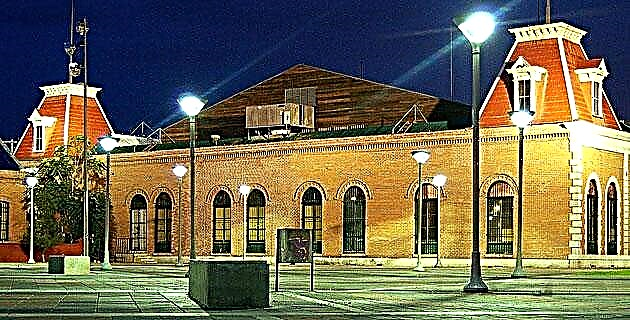

He began as a teacher of lithography in 1883 at the Preparatory School; He stayed there until July 18, 1888, when due to a disastrous flood, he moved to Mexico City. Preceded by great fame as an engraver, he was hired by Irenio Paz to illustrate a large number of magazines and publications.

The abundance of work prompted him to set up his own workshop at number 1 of the closed Santa Teresa, now owned by the lawyer Verdad, where he works in public view, and then at number 5 of Santa Inés, today Moneda.

In 1899, on the death of Manuel Manilla Posada, he formally replaced him in the workshop of Don Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, the most popular editor of street gazettes, corridos, comics, riddles and many other publications.

Together with Blas, son of Don Antonio; the engraver Manilla, who taught Posada to aggravate on zinc; the poet Constancio S. Suárez and the writers Ramón N. Franco, Francisco Ozácar, Raimundo Díaz Guerrero and Raimundo Balandrano, formed a great team that after a year flooded the country with their stories, comics, songs, stories, comedies, almanacs and calendars.

In addition to the newspapers La Gaceta Callejera and Don Chepito, they also published flyers of brown paper in all the colors of the rainbow, which cost one or two cents, and games such as La Oca, which have been the delight of children and adults for many generations, of which more than five million copies have been made to date.

The large volume of work forced Posada to seek more expeditious techniques. This is how he discovered zincography, which consists of drawing with scrap ink on zinc foil, and then hollowing out the whites with an acid bath.

“The almost 20 thousand engravings that Posada made, with the interesting texts and verses that accompany it, describe one of the most interesting times of the long-awaited metropolis, with its 'Porfirian peace' or 'hot peace': the street riots, the fires, earth tremors, comets, end-of-world threats, the birth of monsters, suicides, executions, miracles, plagues, great loves and great tragedies; Everything was captured by this man who was, at the same time, a sensitive antenna for all vibrations and a recording needle for all events ”(Rodríguez, 1977).

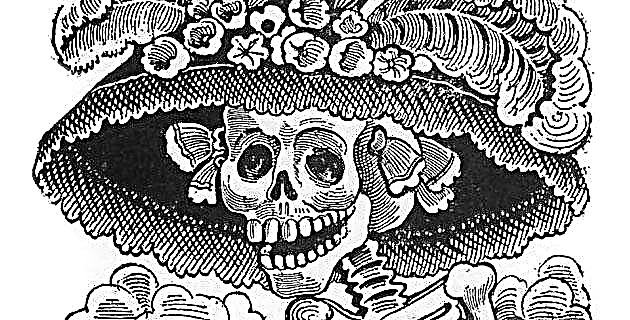

His great love for his country prompted him to develop one of the themes that have most obsessed Mexicans since pre-Hispanic times: death, but not a solemn and fear-inspiring death as it was seen by the higher classes or Catrinas, and Europeans. of his time. He did not represent sad and solemn deaths, but gave life to their skulls with a thousand images or things, immoralizing dynamics; funny skulls with which the people fully identified, because they were a means of relief or revenge against everything that caused them discomfort.

There is no single subject that Don Lupe, as Posada was affectionately called, has left without a skull, who covered everything and everyone, without leaving a puppet with a head, from the humblest of Mexicans to the most exalted politician of his time, of the simplest facts to those of more resonance.

Among the many characters developed by Posada, there are, in addition to his popular skulls, the Devil and Don Chepito Marihuano; but mainly simple people with their joys and sufferings.

“Just as Goya included in his engravings of Caprichos, Scenes from the world of witches to exercise his social criticism, Posada resorts to the other side of life: death, to intensify his social criticism always with a humorous sense, which allows him to use ridicule and extravagance. The scenes and figures from the ‘beyond’ are nothing but the ‘more here’, but transfigured in the world of skulls and skeletons that have full life… ”(ibit.).

The Mexican skull tradition, started by Gabriel Vicente Gahona, called "Picheta", was wonderfully continued and surpassed by Posada, who consolidated, in the Mexican way, the medieval European concept of "the macabre dance", based on the art of dying well. collaborating in this way to the sublimation of feelings and creativity of the people that led, by necessity, to the intensification of the festivities dedicated to their deceased.

The engraver Manuel Manilla owes the invention, at the end of the last century, of the sweet skulls that enriched the tradition of the Day of the Dead and that now, made of sugar, chocolate or joy, with their tinned and shining eyes and with the name of the deceased on the forehead, represent one of its main symbols.

When the Jalisco painter Gerardo Murillo, called “Doctor Atl”, wrote his work Las artes popular en México in two volumes in 1921, he ignored the artistic expressions of the Day of the Dead celebration, as well as Posada's work.

The French painter Jean Charlot, who joined the Mexican School of Painting, is credited with discovering the engraver Posada in 1925. From then on, the populist concept of death that manifests itself by hand, inspired by his work, takes hold. with the support of painters Diego Rivera and Pablo O'Higgins. In the 1930s, the idea of festive contempt for death arose, perhaps based on the funny, funny and not very solemn skulls of Posada.

Among his most important skull engravings are: Don Quixote de la Mancha, trying to straighten one-eyed, riding in an impetuous stampede on his rocinante horse, producing pain and death in his wake. The cycling skulls, a perfect satire to the mechanical progress that tradition casts. With the Adelita Skull, Maderista Skull and Huertista Skull, he represents various political figures of that time, such as the fierce criticism of the bloody revolution of 1910.

The sparkling and funny skull of Doña Tomasa and Simón el Aguador, represents neighborhood gossip. A small series of Skulls of Cupid illustrates some of the versified texts of Constancio S. Suárez.

La Calavera Catrina, as well as Calavera del Catrín and Espolón contra navaja are among the works that have the greatest diffusion worldwide, as they are the most representative of Posada.

Among other engravings, there are Gran fandango and francachela de todos las calaveras and Rebumbio de calaveras, which are accompanied by the following poem, very much in keeping with the celebrations of the Day of the Dead:

The great opportunity to really have fun has arrived, the skulls will be their party in the pantheon.

The sepulchral festivities will last for many hours; the dead will attend with special dresses.

With great anticipation skulls and skeletons have been made complete costumes that will be worn at the meeting.

At nine in the morning of winter January 20, 1913, at house no. 6, on the ground floor of Avenida de la Paz (currently No. 47 on Calle del Carmen), at the age of 66 José Guadalupe Posada died. Because of his poverty, he was buried in a sixth class grave in the Civil Pantheon of Dolores.

“… And instead of becoming a Skull of the pile as he had foreshadowed, he rises from the (common) grave to immortality, to walk again through the twists and turns of the world: sometimes in a frock coat and bowler hat, and other times with the burin in hand awaiting new events ”(ibid.).

Source: Unknown Mexico No. 261 / November 1998