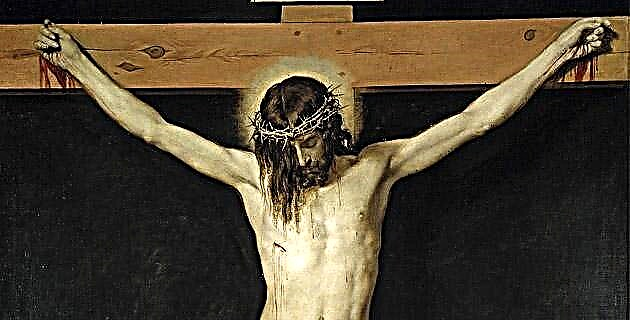

The painting on parchment of a crucified Christ to which we will refer presents unknowns that research has not been able to decipher.

It is not clear whether the work originally belonged to or was part of a composition as an exempt work. The only thing we can say is that it was cut out and nailed to a wooden frame. This important painting belongs to the Museo de El Carmen and is not signed by its author, although we can assume that originally it was.

As there was not enough information and due to the importance of this work, the need arose to carry out an investigation that not only allowed us to place it in time and space, but also to know the techniques and materials used in its manufacture to guide us in restoration intervention, since the work is considered atypical. To get a general idea of the origins of painting on parchment, it is necessary to go back to the very moment when books were illuminated or miniaturized.

One of the first references in this regard seems to indicate it to us Pliny, towards the 1st century AD, in his work Naturalis Historia he describes some wonderful colored illustrations of plant species. Due to disasters such as the loss of the Library of Alexandria, there are only a few fragments of illustrations on papyrus that show events framed and in sequence, in such a way that we could compare them with current comic strips. For several centuries, both papyrus scrolls and codices on parchment competed with each other, until in the 4th century AD the codex became the dominant form.

The most common illustration was the framed self-portrait, occupying only a portion of the available space. This was slowly modified until it took up the entire page and became an exempt work.

Manuel Toussaint, in his book on colonial painting in Mexico, tells us: "A universally recognized fact in the history of art is that painting owes a large part of its rise, like all the arts, to the Church." To have a true perspective on how painting came to be in Christian art, one must keep in mind the vast collection of ancient illuminated books that endured through the centuries. However, this lavish task did not arise with the Christian religion, but rather it had to adapt to an old and prestigious tradition, not only changing the technical aspects, but also adopting a new style and composition of the scenes, which thus became effective. narrative forms.

Religious painting on parchment reaches its climax in the Spain of the Catholic Monarchs. With the conquest of New Spain, this artistic manifestation was introduced to the new world, gradually merging with the indigenous culture. Thus, for the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the existence of a New Spain personality can be affirmed, which is reflected in magnificent works signed by artists as renowned as those of the Lagarto family.

The Crucified Christ

The work in question has irregular measurements as a result of the mutilation of the parchment and the deformations resulting from its deterioration. It shows clear evidence of having been partially attached to a studded wooden frame. The painting receives the generic name of Calvary, since the image represents the crucifixion of Christ and at the foot of the cross shows a mound with a skull. A stream of blood gushes from the right rib of the image and is collected in a ciborium. The background of the painting is very dark, high, contrasting with the figure. In this, the texture is used, the natural color is that of the parchment to, thanks to glazes, obtain similar tones on the skin. The composition that is achieved in this way reveals great simplicity and beauty and is attached in its elaboration to the technique used in miniature paintings.

Almost a third of the work appears attached to the frame by means of tacks, the rest had detached, with losses on the shore. This can be basically attributed to the nature of the parchment itself, which when exposed to changes in temperature and humidity undergoes deformations with the consequent detachment of the paint.

The pictorial layer presented innumerable cracks derived from the constant lime contraction and expansion (mechanical work) of the support. In the folds thus formed, and due to the very rigidity of the parchment, the accumulation of dust was greater than in the rest of the work. Around the edges were rust deposits derived from the studs. Likewise, in the painting there were areas of superficial opacity (stunned) and missing polychromy. The pictorial layer It had a yellowish surface that did not allow visibility and, finally, it is worth mentioning the poor condition of the wooden frame, completely moth-eaten, which forced its immediate elimination. Samples of paint and parchment were taken from the lagging fragments to identify the constituent materials of the work. The study with special lights and with a stereoscopic magnifying glass indicated that it was not possible to obtain paint samples from the figure, because the pictorial layer in these areas consisted only of glazes.

The result of the laboratory analyzes, the photographic records and the drawings made up a file that would allow a correct diagnosis and treatment of the work. On the other hand, we can affirm, based on the iconographic, historical and technological evaluation, that this work corresponds to a temple to the tail, characteristic of the seventeenth century.

The support material is a goatskin. Its chemical state is very alkaline, as can be assumed from the treatment that the skin undergoes before receiving the paint.

Solubility tests showed that the paint layer is susceptible to most of the commonly used solvents. The varnish of the pictorial layer in whose composition the copal is present, is not homogeneous, since in some parts it appears shiny and in others matt. Due to the above, we could summarize the conditions and challenges presented by this work by saying that, on the one hand, to restore it to the plane, it is necessary to moisten it. But we have seen that water solubilizes pigments and therefore would damage paint. Likewise, it is required to regenerate the flexibility of the parchment, but the treatment is also aqueous. Faced with this contradictory situation, the research focused on identifying the appropriate methodology for its conservation.

The challenge and some science

From what has been mentioned, water in its liquid phase had to be excluded. Through experimental tests with illuminated parchment samples, it was determined that the work was subjected to a controlled wetting in an airtight chamber for several weeks, and subjecting it to pressure between two glasses. In this way the recovery of the plane was obtained. A mechanical surface cleaning was then carried out and the pictorial layer was fixed with a glue solution that was applied with an air brush.

Once the polychromy was secured, the treatment of the work from the back began. As a result of the experimental part carried out with fragments of the original painting recovered from the frame, the definitive treatment was carried out exclusively on the back, subjecting the work to applications of the flexibility regenerating solution. The treatment lasted for several weeks, after which it was observed that the support of the work had largely recovered its original condition.

From this moment on, the search for the best adhesive began that would also cover the function of being compatible with the treatment carried out and allow us to place an additional fabric support. It is known that parchment is a hygroscopic material, that is, that it varies dimensionally depending on changes in temperature and humidity, so it was considered essential that the work was fixed, on a suitable fabric, and then it was tensioned on a frame.

Cleaning the polychromy allowed the beautiful composition to be recovered, both in the most delicate areas and in those with the highest pigment density.

For the work to recover its apparent unity, it was decided to use Japanese paper in the areas with missing parchment and superimposing all the layers that were necessary to obtain the level of the painting.

In the color lagoons, the watercolor technique was used for chromatic reintegration and, to finish the intervention, a superficial layer of protective varnish was applied.

In conclusion

The fact that the work was atypical led to a search for both the appropriate materials and the most appropriate methodology for its treatment. The experiences carried out in other countries served as the basis for this work. However, these had to be adapted to our requirements. Once this objective was resolved, the work was subjected to the restoration process.

The fact that the work would be exhibited decided the form of assembly, which after a period of observation has proven its effectiveness.

The results were not only satisfactory for having managed to stop the deterioration, but at the same time, very important aesthetic and historical values for our culture were brought to light.

Finally, we must recognize that although the results obtained are not a panacea, since each cultural asset is different and the treatments must be personalized, this experience will be useful for future interventions in the history of the work itself.

Source: Mexico in Time No. 16 December 1996-January 1997