Immersed in two great deeds of the 20th century, the struggle for the social ideals of the Communist Party and the construction of a post-revolutionary Mexican art, the photographer Tina Modotti has become an icon of our century.

Tina Modotti was born in 1896 in Udine, a city in northeastern Italy that at that time was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and had a tradition of worker-craft organization. Pietro Modotti, a well-known photographer and his uncle, is perhaps the first to introduce her to the magic of the laboratory. But in 1913 the young man left for the United States, where his father had emigrated, to work in California like so many other Italians forced to leave their homeland due to the poverty of their region.

Tina must learn a new language, join the world of factory work and the growing labor movement - powerful and heterogeneous - of which her family was a part. Shortly after, she met the poet and painter Roubaix de L’Abrie Richey (Robo), whom she married, coming into contact with the diverse intellectual world of post-WWI Los Angeles. Her legendary beauty grants her a role as a rising silent film star in the fledgling Hollywood industry. But Tina will always be linked to characters that will allow her to follow the path that she herself is choosing, and a list of her companions now offers us a true map of her interests.

Robo and Tina come into contact with some Mexican intellectuals such as Ricardo Gómez Robelo, who emigrated due to the complex post-revolutionary political situation in Mexico and, especially Robo, are fascinated by the myths that are beginning to form part of the history of Mexico in the 1920s. During this period, he met the American photographer Edward Weston, another decisive influence in his life and career.

Art and politics, the same commitment

Robo visits Mexico where he dies in 1922. Tina is forced to attend the funeral and falls in love with the artistic project that is being developed. Thus in 1923 he emigrated again to the country that would be the source, promoter and witness of his photographic work and his political commitment. This time he starts with Weston and with the project of both, she to learn to photograph (in addition to mastering another language) and he to develop a new language through the camera. In the capital they quickly joined the group of artists and intellectuals that revolved around the whirlwind that was Diego Rivera. Weston finds the climate conducive to his work and Tina to learn as his assistant of the meticulous laboratory work, becoming his indispensable assistant. Much has been said about the climate of that moment where artistic and political commitment seemed indissoluble, and that in the Italian it meant the link with the small but influential Mexican Communist Party.

Weston returns to California for a few months, which Tina takes advantage of to write short and intense letters that allow us to trace his growing convictions. Upon the return of the American both exhibited in Guadalajara, receiving praise in the local press. Tina too must return to San Francisco, at the end of 1925 when her mother died. There she reaffirms her artistic conviction and acquires a new camera, a used Graflex that will be her faithful companion for the next three years of maturity as a photographer.

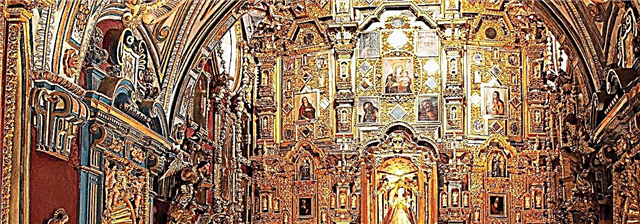

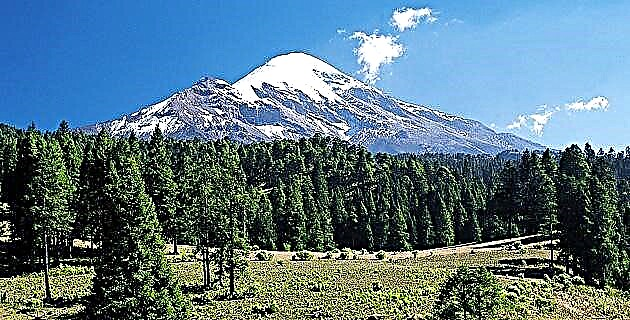

Upon returning to Mexico, in March 1926, Weston began the project of portraying crafts, colonial architecture and contemporary art to illustrate Anita Brenner's book, Idols behind the altars, which will allow them to tour a part of the country (Jalisco, Michoacán, Puebla and Oaxaca) and delve into popular culture. Towards the end of the year Weston leaves Mexico and Tina begins her relationship with Xavier Guerrero, a painter and active member of the PCM. However, he will maintain an epistolary relationship with the photographer until the beginning of his residence in Moscow. In this period, she combines her activity as a photographer with her participation in the tasks of the Party, which strengthens her contacts with some of the most avant-garde creators of culture of that decade, both Mexicans and foreigners who came to Mexico to witness the cultural revolution. Of which so much was spoken.

His work begins to appear in cultural magazines such as Shape, Creative Art Y Mexican Folkways, as well as in left-wing Mexican publications (The Machete), German (AIZ) American (New Masses) and Soviet (Puti Mopra). Likewise, it records the work of Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, Máximo Pacheco and others, which allows him to study in detail the different artistic proposals of the muralists of that time. In the second half of 1928, he began his love affair with Julio Antonio Mella, a Cuban communist exiled in Mexico that would mark his future, since in January of the following year he was assassinated and Tina was involved in the investigations. The country's political climate was exacerbated and persecution of opponents of the regime was the order of the day. Tina stays until February 1930, when she is expelled from the country accused of participating in a plot to assassinate the newly elected president, Pascual Ortiz Rubio.

In this hostile climate, Tina carries out two fundamental projects for her work: she travels to Tehuantepec where she takes some photographs that mark a shift in her formal language that seems to be heading towards a freer way, and in December she holds her first personal exhibition . This takes place in the National Library thanks to the support of the then rector of the National University, Ignacio García Téllez and Enrique Fernández Ledesma, director of the library. David Alfaro Siqueiros called it "The first revolutionary exhibition in Mexico!" Having to leave the country in a few days, Tina sells most of her belongings and leaves some of her photographic materials with Lola and Manuel Álvarez Bravo. Thus begins the second stage of emigration, linked to his political work that increasingly dominates his existence.

In April 1930, she arrived in Berlin where she tried to work as a photographer with a new camera, the Leica, which allows greater mobility and spontaneity, but which she found contrary to her elaborate creative process. Disenchanted by her difficulty in working as a photographer and concerned about Germany's changing political direction, she left for Moscow in October and fully joined the work at Socorro Rojo Internacional, one of the auxiliary organizations of the Communist International. Little by little, he abandons photography, reserving it to record personal events, dedicating his time and effort to political action. In the Soviet capital, he affirms his link with Vittorio Vidali, an Italian communist, whom he had met in Mexico and with whom he will share the last decade of his life.

In 1936 she was in Spain, fighting for the victory of the republican government from the communist faction, until in 1939 she was forced to emigrate again, under a false name, before the defeat of the Republic. Back in the Mexican capital, Vidali began a life away from her old artist friends, until death surprises her, alone in a taxi, on January 5, 1942.

A Mexican work

As we have seen, the photographic production of Tina Modotti is limited to the years lived in the country between 1923 and 1929. In this sense, her work is Mexican, so much so that it has come to symbolize some of the aspects of life in Mexico during those years. . The influence that his work and that of Edward Weston had on the Mexican photographic environment is now part of the history of photography in our country.

Modotti learned from Weston the careful and thoughtful composition to which he always remained faithful. At first Tina privileged the presentation of objects (glasses, roses, canes), later she concentrated on the representation of industrialization and architectural modernity. He portrayed friends and strangers who should be testimony to the personality and condition of people. Likewise, she recorded political events and produced series in order to build emblems of work, motherhood, and revolution. His images acquire an originality beyond the reality they represent, for Modotti the important thing is to make them transmitters of an idea, a state of mind, a political proposal.

We know of his need to compress experiences through the letter he wrote to the American in February 1926: “Even the things that I like, the concrete things, I am going to make them go through a metamorphosis, I am going to turn them into concrete things. abstract things ”, A way to control the chaos and“ unconsciousness ”that you encounter in life. The same selection of the camera makes it easier for you to plan the final result by allowing you to perceive the image in its final format. Such assumptions would make one think of a study where all the variables are under control, on the other hand, he worked constantly in the street as long as the documentary value of the images was fundamental. On the other hand, even his most abstract and iconic photographs tend to convey the warm imprint of human presence. Towards the end of 1929 he wrote a short manifesto, About photography, as a result of the reflection to which it is forced on the occasion of its exhibition; a kind of balance of his artistic life in Mexico before the imminence of his departure. His departure from the fundamentally aesthetic principles underlying Edward Weston's work is appreciable.

However, as we saw, his work goes through different stages that go from the abstraction of elements of everyday life to portraiture, registration and the creation of symbols. In a broad sense, all these expressions can be encompassed within the concept of document, but the intention is different in each one. In his best photographs, his formal care in framing, cleanliness of forms and the use of light that generates a visual journey is evident. He achieves this through a fragile and complex balance that requires prior intellectual elaboration, which is later complemented by hours of work in the darkroom until he achieves the copy that satisfied him. For the artist, it was a job that allowed him to develop his expressive capacity, but which, therefore, reduced the hours dedicated to direct political work. In July 1929 he confessed epistolary to Weston: "You know Edward that I still have the good pattern of photographic perfection, the problem is that I have lacked the leisure and tranquility necessary to work satisfactorily."

A rich and complex life and work that, after remaining semi-forgotten for decades, have led to an endless number of writings, documentaries and exhibitions, which have not yet exhausted their possibilities of analysis. But, above all, a production of photographs that must be seen and enjoyed as such. In 1979 Carlos Vidali donated 86 negatives of the artist to the National Institute of Anthropology and History in the name of his father, Vittorio Vidali. This important collection was integrated into the INAH National Photo Library in Pachuca, then just founded, where it is conserved as part of the country's photographic heritage. In this way, a fundamental part of the images that the photographer made remains in Mexico, which can be seen in the computerized catalog that this institution has been developing.

artDiego Riveraextranjeros en méxicophotografasfridahistory of photography in mexicointelectuales mexicoorozcotina modottiRosa Casanova