During pre-Hispanic times, in the territory occupied by the current Mexican Republic, and with an antiquity that dates back to 30 thousand years in its prehistoric times, diverse human groups with different degrees of socio-political integration and cultural development coexisted until the time of the contact with Spanish culture.

In the middle of them would be intermediate, although not indeterminate, the so-called Oasisamérica. The settlers of the first had a "high culture" whose maximum expression, in the stage immediately prior to the Conquest, was the Triple Alliance, also known as the Empire of Moctezuma. In turn, the Arido-American groups - despite having been the origin of a good part of the migrations that, in the long run, would make Mesoamerican achievements possible - remained with a lower degree of cultural development and lower levels in terms of forms of organization. sociopolitical is concerned. The Oasisamericans fluctuated between the other two, while at the same time being their intermediaries. In other words, at the time of contact, the indigenous world was a multiethnic and multicultural mosaic with marked differences between its components. However, in the Mesoamerican super-area there was a common cultural substrate. One of the characteristics that distinguished a good part of their societies was - in addition to the possession and use of caIendarios, a type of state organization and various forms of urban planning - the manufacture of pictographic records that recorded, among others, religious-caIendric aspects. , political-military, divinatory, tributary, genealogical, cadastral and cartographic, which in an important way (in certain cases) testified to a strong historical awareness.

According to Alfonso Caso, this tradition can be traced back to the 7th or 8th centuries of our era, and according to Luis Reyes it is linked to cave paintings, ceramic complexes and wall paintings that are at least two thousand years old. In Kirchhoff's opinion, the second piece of information gives us the opportunity to combine archaeological data with [the] pictorial or written sources.

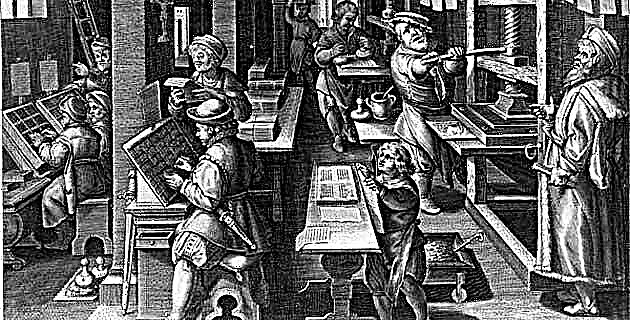

Pictographic records, a unique characteristic of Mesoamerican high culture in the now American continent, continued in profusion during the colonial era, basically as a means of legitimizing ancient privileges, claims on lands or boundaries, validation of lineages, and as a certain form of memorials. of services rendered to the Crown by the indigenous communities and their chiefs.

In any case, as Luis Reyes points out, the existence of pictographic testimonies during the Colony demonstrates the strong roots and vitality of the Indian writing system, which changed and adapted but persisted throughout the colonial era. It also indicates the acceptance and colonial recognition of the cultural specificity of the Indians.

As a documentary historical heritage, these testimonies serve as a bridge, since backwards it connects us with the producers of the now archaeological remains (be they these utensils or imposing monumental areas) and forward, with current indigenous groups. In terms of Paul Kirchhoff, it allows us to study the Mesoamerican historical process (in a broad sense), to attempt its reconstruction from its origins to the present. To this end they would have to unite their efforts archaeologists, historians and anthropologists; although it is essential to add that, from 1521, for its full understanding, it would be necessary to take into account the Spaniards, and later, according to their moment of insertion into colonial society, Africans and Asians.

The Mesoamerican codices publishing project brings together the efforts of many people and institutions. The latter are the National Institute of Anthropology and History, the Benemérita University of Puebla, the Center for Research and Higher Studies in Social Anthropology and the General Archive of the Nation.

With the culmination of this project, through the study and publication of a facsimile, the rescue of the following colonial indigenous pictographic testimonies is made possible:

The Tlatelolco Codex, with an introductory study by the teacher Perla Valle, describes the social, political and religious situation and the way in which this indigenous partiality was inserted into the nascent colonial society in which, to a large extent, old organizational forms were used. pre-Columbian, especially in the political and economic aspects.

The Coatlichan Map, analyzed by the teacher Luz María Mohar, due to its plastic characteristics, although with certain European influences, can be considered an example of the persistence of the indigenous style and of its concern to capture graphically the places of settlement of its different units sociopolitical and the environment that surrounded them.

The Yanhuitlán Codex, studied by the teacher María Teresa Sepúlveda and Herrera, (published together for the first time, the two known fragments of it), deals basically with historical and economic events that occurred in Yanhuitlán and some neighboring towns, in the early colonial times between 1532 and 1556.

The Cozcatzín Codex, with a preliminary study by the teacher Ana Rita Valero, a singular example of the thematic variation of the colonial codices, has a historical, genealogical, economic and astronomical-astrological content. It is a typically Tenochca source as shown, among other aspects, by the detailed description of the “civil war” between the Mexica: Tenochcas and Tlatelolcas, with an unfortunate ending for the latter.

Cuauhtinchan map number 4, analyzed by the teacher Keiko Yoneda, is perhaps the most European cartographic representation of the region, a privileged place in terms of the wealth of colonial pictographic testimonies and documentaries. Its main purpose is to point out the boundaries between Cuauhtinchan and the ancient and adjoining pre-Hispanic manors, and the city of Puebla de los Ángeles, at that time emerging. The materialization of the Mesoamerican codices edition project, it is worth insisting on it, shows the goodness and effectiveness of inter-institutional collaboration and the need for interdisciplinary work, for the effective rescue of that written, pictographic and documentary memory, basic for the reconstruction of the future of a good part of the indigenous ethnic groups participating in the formation of colonial society, whose descendants currently make up important segments of this our Mexico, fortunately, as in its beginnings, pluri-ethnic and multicultural.

Source: Mexico in Time No. 8 August-September 1995