Following the trail of the explorers and missionaries who made the first routes in Baja California territory, the expedition from unknown Mexico set out in the same direction, first on foot and then by bicycle, to finish navigating in a kayak. Here we have the first stage of these adventures.

Following the trail of the explorers and missionaries who made the first routes in Baja California territory, the expedition from unknown Mexico set out in the same direction, first on foot and then by bicycle, to finish navigating in a kayak. Here we have the first stage of these adventures.

We started this adventure in order to follow in the footsteps of those ancient Baja California explorers, although we were equipped with modern sports equipment.

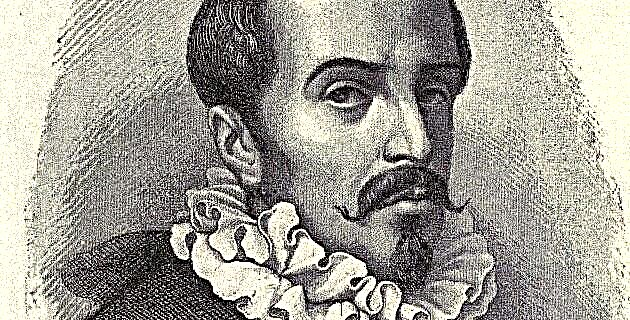

The immense quantity of pearls in the bay of La Paz was irresistible for Hernán Cortés and his sailors, who first set foot on the Baja California territory on May 3 in 1535. Three ships with approximately 500 people arrived to stay there for two years. , until the different obstacles, including the hostility of the Pericúes and the Guaycuras, forced them to leave the territory. Later, in 1596, Sebastián Vizcaíno sailed along the west coast, and thanks to this he was able to make the first map of Baja California, which was used by the Jesuits for two hundred years. Thus, in 1683 Father Kino founded the mission of San Bruno, the first of the twenty missions throughout the territory.

For historical, logistical and climatological reasons, we decided to make the first expeditions in the southern part of the peninsula. The trip was made in three stages; the first (which is narrated in this article) was done on foot, the second by mountain bike and the third by sea kayak.

A connoisseur of the region told us about the walking route that the Jesuit missionaries followed from La Paz to Loreto, and with the idea of rediscovering the road, we began to plan the trip.

With the help of old maps and INEGI, as well as Jesuit texts, we found the ranchería de Primera Agua, where the gap that comes from La Paz ends. At this point our walk begins.

It was necessary to make many calls through the La Paz radio station to communicate with a muleteer in the region who could get donkeys and who knew the way. We made the messages at 4:00 p.m., at which time the fishermen of San Evaristo communicate with each other to say how much fish they have and to know if they will collect the product that day. Finally we contacted Nicolás, who agreed to meet us in the afternoon of the next day at Primera Agua. Sponsored by the Centro Comercial Californiano we get much of the food, and with the help of Baja Expeditions from Tim Means, we pack the food in plastic boxes to tie to the donkeys. Finally the day of departure arrived, we climbed the twelve javas in Tim's truck and after traveling four hours of dusty dirt, hitting our heads, we arrived at Primera Agua: some stick houses with cardboard roofs and a small garden was the only thing there was, besides the goats of the locals. "They come from Monterrey, Nuevo León, to buy our animals," they told us. Goats are their only economic sustenance.

Late in the day we began to walk the path of the Jesuit missionaries. The muleteers, Nicolás and his assistant Juan Méndez, went ahead with the donkeys; then John, an American hiking geologist, Remo, also American and a builder in Todos Santos; Eugenia, the only woman who dared to challenge the burning sun and the torture that awaited us on the road, and finally Alfredo and I, reporters from unknown Mexico, who always wanted to take the best photograph, we stayed behind.

At first the path was distinguished quite well, since the locals use it to look for firewood and carry the animals, but little by little it disappeared until we found ourselves walking across the country. The shade of the plants and the cacti did not serve as shelter from the sun, and so we continued tripping over the red stones until we found a stream that strangely had water. The donkeys, who seldom make such heavy days, threw themselves to the ground. The food was simple here and throughout the trip: tuna sandwiches and an apple. We could not afford to bring other types of food because we needed space to carry the water.

There was really nothing to tell us that this was the path of the missionaries, but when we analyzed the maps we understood that it was the simplest route, without so many ascents and descents.

Sunny, we reached the table in San Francisco, where we found the tracks of some deer. The donkeys, no longer loaded, fled in search of food, and we, lying on the ground, did not agree to prepare dinner.

We were always worried about the water, because the sixty liters that the donkeys carried were disappearing quickly.

To take advantage of the coolness of the morning, we set up camp as fast as we could, and it is that ten hours of walking under the rays of the sun and on wild terrain is a serious thing.

We passed by the side of a cave and continuing along the road we came across the Kakiwi plains: a plain that measures 5 km from west to east and 4.5 km from south to north, which we took. The towns that surround this plain were abandoned more than three years ago. What was a privileged place for planting is now a dry and desolate lake. Leaving the last abandoned town on the shores of this lake, we were welcomed by the breeze from the Sea of Cortez, which from a height of 600 m we could enjoy at our ease. Below, a little to the north, you could see the Los Dolores ranch, the place we wanted to get to.

The slope that zigzagged next to the mountains took us to the oasis "Los Burros". Among date palms and next to a gush of water, Nicolás introduced us to the people, apparently distant relatives.

Fighting with the donkeys to keep them from falling to the ground, the afternoon fell. The steps we took on the loose sand, in the streams, were slow. We knew we were close, because from above the mountains we saw the ruins of the Los Dolores ranch. Finally, but in the dark, we found the fence of the ranch. Lucio, friend of Nicolás, our muleteer, received us in the house, a construction from the last century.

Looking for the Jesuit missions, we walked 3 km to the west to arrive at the Los Dolores mission, founded in 1721 by Father Guillén, who was the creator of the first road to La Paz. At that time this place gave rest to the people who traveled from Loreto to the bay.

By 1737 Fathers Lambert, Hostell, and Bernhart had reestablished the mission to the west, on one side of the La Pasión stream. From there, the visits of the religious to other missions in the region were organized, such as La Concepción, La Santísima Trinidad, La Redención and La Resurrección. However, in 1768, when the Los Dolores mission numbered 458 people, the Spanish crown ordered the Jesuits to abandon this and all other missions.

We found the ruins of the church. Three walls built on a hill next to the stream, the vegetables that Lucio's family planted and a cave, which due to its shape and dimensions could have been the missionaries' cellar and cellar. If today, having not had rain since: three years ago, it is still an oasis, in the time when the Jesuits inhabited it it must have been a paradise.

From here, from the Los Dolores ranch, we realized that our friend Nicolás no longer knew the way. He didn't tell us, but as we were walking in opposite directions to the one we had planned on the maps, it became apparent that he couldn't find the route. First stuck to the hill, 2 km inland, and then on ball stone, next to where the waves break, we walked until we found the gap. It was difficult to walk by the sea; the donkeys, terrified by the water, tried to find their way among the cacti, throwing away all the javas. In the end, each of us ended up pulling a donkey.

The gap is in such bad shape that not a 4 x 4 truck would make it through. But for us, even with back pain and blistered toes, it was a comfort. We were already heading in a safe direction. When we had traveled 28 km in a straight line from Los Dolores we decided to stop and set up camp.

We never lacked sleep, but every day when we woke up there were comments from Romeo, Eugenia and even mine about the different pains we had in the body due to physical effort.

Tying the load on the donkeys took us an hour, and therefore we decided to go ahead. In the distance we managed to see a two-story house from the last century, recognizing that the town of Tambabiche was nearby.

People welcomed us kindly. While we had coffee in one of the cardboard houses that surround the house, they told us that Mr. Donaciano, upon finding and selling a huge pearl, moved with his family to Tambabiche. There he had the huge two-story house built to continue searching for pearls.

Doña Epifania, the oldest lady in town and the last to live in Donaciano's house, proudly showed us her jewelry: a pair of earrings and a gray pearl ring. Definitely a well preserved treasure.

They are all distant relatives of the founder of the town. Touring the houses to learn more about their history, we came across Juan Manuel, “El Diablo”, a man with a thick and lame complexion, who with a crooked lip told us about fishing and how he came to find this place. “My wife,” he said hoarsely, “is the daughter of Doña Epifania and I lived on the San Fulano ranch, I used to grab my male and within a day he was here. They didn't love me very much, but I insisted ”. We were lucky to meet him because we could no longer trust Nicolás. For a good price, "El Diablo" agreed to accompany us on our last day.

We found refuge in Punta Prieta, near Tambabiche. Nicolás and his assistant cooked us an exquisite grilled snapper.

At ten in the morning, and advanced on the road, our new guide appeared. To get to Agua Verde, you had to pass between the mountains, four great passes, as the highest part of the hills is known. "El Diablo", who did not want to walk back, showed us the path that went up to the port and returned to his panga. When we had crossed we would run into him again and the same scene would repeat itself; Thus we passed through the Carrizalito, San Francisco and San Fulano ranch to Agua Verde, where we arrived after forcing the donkeys to pass over a cliff.

To leave San Fulano ranch, we walked for two hours until we reached the town of Agua Verde, from there we followed the path of the missions by mountain bike. But that story will continue in another article to be published in this same magazine.

After traveling 90 km in five days, we found that the path used by the missionaries is largely erased from history, but could easily be cleaned up by reconnecting the missions by land.

Source: Unknown Mexico No. 273 / November 1999