Our proverbial taste for preserving memorable objects or admiring old buildings is translated into a nostalgic memory when we express phrases such as “this was not like that”; or "everything about these streets has changed, except that building."

This evocation, of course, occurs in all of our cities or at least in the area of what urban planners call the "historic center", where the memory is also coupled with the rescue and conservation of real estate.

It is, undoubtedly, about rehabilitating the oldest parts of the cities for housing, tourism, educational, economic and social purposes. From this perspective, in recent years the historic center of Mexico City has been the object of attention from both government authorities and private companies.

It seems a miracle to still see buildings in the country's capital that are 200 or 300 years old, especially when it comes to a city hit by earthquakes, riots, floods, civil wars and especially by the real estate depredations of its inhabitants. In this sense, the old town of the capital of the country fulfills a double purpose: it is the receptacle of the most significant buildings in the history of Mexico and at the same time a sample of urban mutations throughout the centuries, from the imprint left by the great Tenochtitlan until the postmodern buildings of the XXI century.

On its perimeter it is possible to admire some buildings that have stood the test of time and that have fulfilled a specific function in the society of their time. But historic centers, like cities in general, are not permanent: they are organisms in constant transformation. As buildings are made of ephemeral materials, the urban profile is constantly changing. What we see of cities is not the same as what their inhabitants saw 100 or 200 years ago. What testimony do we have of what cities were like? Perhaps literature, oral stories, and of course, photography.

THE ANSWER OF TIME

It is difficult to think of a "historic center" preserved in its "original!" Conception, because time is in charge of shaping it: buildings are built and many others collapse; Some streets are closed and others are opened. So what is "original"? Rather, we find reused spaces; buildings destroyed, others under construction, widened streets and an incessant modification of the urban environment. A sample of photographs from the 19th century of certain spaces in Mexico City can give us some idea of the city mutations. Although these sites exist today, their purpose has changed or their spatial arrangement has been modified.

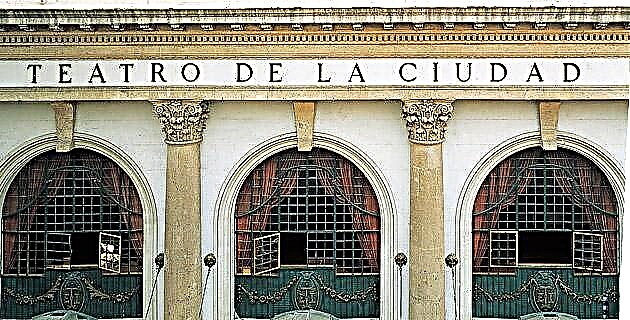

In the first photograph we see the old 5 de Mayo street, taken from the west tower of the Metropolitan Cathedral. In this view to the west, the old Main Theater stands out, once called the Santa Anna Theater, demolished between 1900 and 1905 to extend the street to the current Palace of Fine Arts. Photography freezes a moment prior to 1900, when this theater was active on the road. On the left you can see the Casa Profesa, still with its towers and the Alameda Central grove in the background.

What is interesting about this view is perhaps the concern it arouses in the observer. Today, for a modest sum, it is possible to climb the towers of the cathedral and admire this same landscape, albeit modified in its composition. It is the same view, but with different buildings, here is the paradox of reality with its photographic reference.

Another site in the historic center is the old convent of San Francisco, of which only one or another chink remains. In the foreground we have the façade of the Balvanera chapel, which faces north, that is, towards Madero street. This photograph may be dated to approximately 1860, or perhaps earlier, as it shows in detail the Baroque high-reliefs that were later mutilated. It is the same as with the previous photograph. The space is still there, albeit modified.

Due to the confiscation of religious assets around the 1860s, the Franciscan convent was sold in parts and the main temple was acquired by the Episcopal Church of Mexico. Towards the end of that century, the space was recovered by the Catholic Church and reconditioned to return to its original purpose. It should be noted that the large cloister of the same former convent is still preserved in good condition and is home to a Methodist temple, which is currently accessible from Calle de Ghent. The property was acquired in 1873 by this also Protestant religious association.

Finally, we have the building of the old convent of San Agustín. In accordance with the Reform laws, the Augustinian temple was dedicated to a public purpose, which in this case would be that of a repository of books. Through a decree of Benito Juárez in 1867, the religious building was used as a National Library, but the adaptation and organization of the collection took time, in such a way that until 1884 the library was inaugurated. For this, its towers and the side portal were demolished; and the front of the Third Order was covered with a façade according to Porfirian architecture. This baroque façade remains bricked up to date. The image we see still preserves this side cover that can no longer be admired today. The convent of San Agustín stood out in the panoramic views of the city, towards the south, as can be seen in the photo. This view taken from the cathedral shows missing constructions, such as the so-called Portal de las Flores, south of the zócalo.

ABSENCES AND MODIFICATIONS

What do the photographs of these buildings and streets tell us, of these absences and of the changes in their social use? In one sense, some spaces shown no longer exist in reality, but in another sense, these same spaces remain in the photograph and therefore in the memory of the city.

There are also modified spaces, such as the Plaza de Santo Domingo, the Salto del Agua fountain or the Avenida Juárez at the height of the Corpus Christi church.

The then singularity of the images refers to the appropriation of a memory that, although not part of our reality, exists. The non-existent places are illuminated in the image, as when at the end of a trip we count the places traveled. In this case, the photograph serves as a memory window.