When we imagine convents, we have to do it thinking of a place where religious live, under the rules dictated by the Catholic Church and those of the Institute or Order to which they belong. But at the end of the 16th century, these areas were schools, workshops, hospitals, farms, gardens and many other things where teaching and learning were realities that existed in harmony.

The first name that the convent received was “claustrum”. In the Middle Ages it was known by the name of "clostrum" or "monasterium". In them lived those who had made solemn vows that could only be dispensed by the Pope.

Apparently, the conventual life has its origin in the ascetic life of the laity who, living in the bosom of a family, chose to fast and dress without luxuries, and who later retired to the deserts, especially to Egypt and lived there in chastity and poverty.

The monastic movement gained strength in the third century after Christ, gradually they were grouped around great figures, such as that of Saint Anthony. From its beginnings until the 13th century, there were only three religious families in the Church: that of San Basilio, that of San Agustín and that of San Benito. After this century, numerous orders arose that acquired a great expansion in the Middle Ages, a phenomenon to which New Spain was not alien in the 16th century.

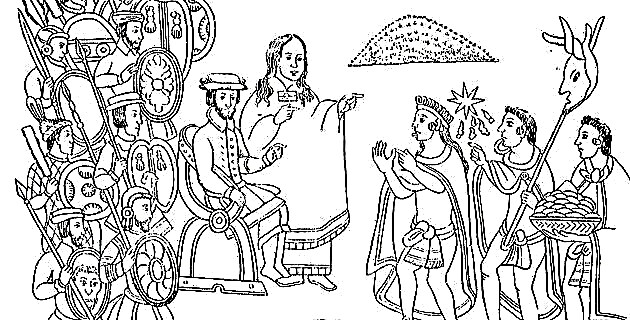

Shortly after the city of Tenochtitlan was defeated, the Spanish Crown saw the need to convert the defeated peoples to Christianity. The Spanish were very clear about their objective: to conquer the natives to increase the number of subjects of Spain, also convincing the indigenous peoples that they were children of God redeemed by Jesus Christ; the religious orders were entrusted with such an important undertaking.

The Franciscans, possessors of a historical tradition and a perfectly defined and consolidated institutional physiognomy since the end of the 15th century, established the first evangelization communities in 1524 in four indigenous centers of great importance, located in the central region of Mexico, extending years later to the north and south of this region, as well as Michoacán, Yucatán, Zacatecas, Durango and New Mexico.

After the Franciscan order, the Preachers of Santo Domingo arrived in 1526. The evangelization tasks of the Dominicans began systematically until 1528 and their work included an extensive territory that included the current state of Tlaxcala, Michoacán, Veracruz, Oaxaca, Chiapas, Yucatán and the Tehuantepec region.

Finally, the constant news from America and the evangelizing work of Franciscans and Dominicans, led to the arrival of the order of St. Augustine in the year 1533. Two masters later formally established themselves, occupying a large territory whose regions were at that time still borders: Otomian, Purépecha, Huasteca and Matlatzinca regions. Wild and poor areas with an extreme climate were the geographical and human terrain on which this order preached.

As evangelization progressed, the dioceses were formed: Tlaxcala (1525), Antequera (1535), Chiapas (1539), Guadalajara (1548) and Yucatán (1561). With these jurisdictions, pastoral care is strengthened and the ecclesial world of New Spain is being defined, where the Divine mandate: "Preach the gospel to every creature", was a primary motto.

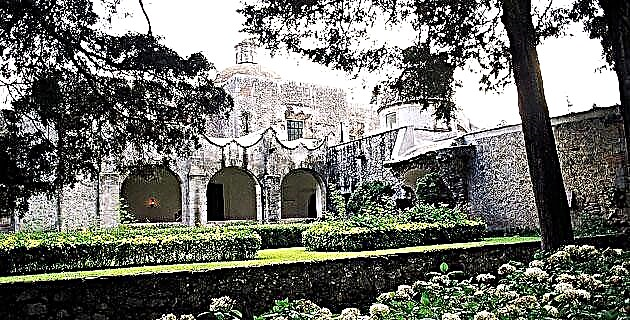

As for the place where they lived and carried out their work, the convent architecture of the three orders was generally adjusted to the so-called “moderate trace”. Its establishments were made up of the following spaces and elements: public spaces, dedicated to worship and teaching, such as the temple with its different sections: choir, basement, nave, presbytery, altar, sacristy and confessional, the atrium, the open chapel, the posas chapels, the atrial crosses, the school and the hospital. The private one, made up of the convent and its different dependencies: cloister, cells, bathrooms, refectory, kitchen, refrigerator, cellars and warehouses, depth room and library. In addition there were the orchard, the cistern and the mills. In all these spaces the daily life of the friars took place, which was subject to the Rule, which is the first mandate that governs an order and to which all possible consultations are directed and, additionally, the Constitutions, a document that makes extensive reference to the daily life of the convent.

Both documents contain the statutes for life in common, clearly pointing out that private property does not exist, that first of all prayer and the mortification of the flesh must be exercised through fasting and modesty. These legislative instruments indicate the government of the communities, the material, spiritual and religious aspects. In addition, each convent was provided with a ceremonial: manual on daily behavior, both individual and collective, where the hierarchical order and the functions of each individual within the religious community were rigorously respected.

Regarding their faith, the orders lived religiously in their convents under the authority of their Provincial and with the daily exercise of prayer. They were obliged to abide by the precepts of the Rule, the Constitutions, the divine office, and obedience.

The guardian was the center of disciplinary administration. Their daily life was subject to strict discipline, except in the holy days, such as the Semana Mayor, on the first Friday of each month and on Sundays, when it was necessary that the schedules and activities vary by virtue of the celebrations, Well, if there were processions on a daily basis, during those days they multiplied. The recitation of the canonical hours, which are the various parts of the office that the Church uses at different times of the day, regulated conventual life. These should always be said in community and in the temple choir. Thus, at midnight Matins were said, followed by an hour of mental prayer, and at dawn morning prayers were said. Then the celebration of the Eucharist took place and, consecutively, throughout the day different offices continued, for all of them the community always had to be together, regardless of the number of religious who inhabited the convent, since this could vary between two and up to forty or fifty friars, depending not only on the type of house, that is, its hierarchy and architectural complexity, but on its geographical location, since it was all dependent on whether it was a major or minor convent, a Vicarage or a visit.

Daytime life ended after the so-called full hours, approximately at eight o'clock at night and from then on the silence should be absolute, but used for meditation and study, a fundamental part of convent life, since we must not forget that these Precincts were characterized and were outstanding in the 16th century as important centers for the study of theology, arts, indigenous languages, history and grammar. In them the first letters schools had their origin, where the children, taken under the tutelage of the friars, were a very important means for the conversion of the natives; hence the importance of conventual schools, especially those run by Franciscans, who also devoted themselves to the teaching of arts and crafts giving rise to guilds.

The rigor of the time meant that everything was measured and numbered: the candles, the sheets of paper, the ink, the habits and the shoes.

The feeding schedules were rigid and the community had to be together to eat, as well as to drink the chocolate. Generally, the friars were provided with cocoa and sugar for breakfast, bread and soup for lunch, and in the afternoon they had water and some sponge cake. Their diet was based on different types of meats (beef, poultry and fish) and fruits, vegetables and legumes grown in the garden, which was a work space from which they benefited. They also consumed corn, wheat and beans. Over time, the preparation of food was mixed with the incorporation of typically Mexican products. The different stews were prepared in the kitchen in ceramic or copper pans, pots and troughs, metal knives, wooden spoons, as well as sieves and sieves of different materials were also used, and molcajetes and mortars were used. The food was served in the refectory in utensils such as bowls, bowls and clay jugs.

The convent's furniture consisted of high and low tables, chairs and armchairs, boxes, chests, trunks and cabinets, all of them with locks and keys. In the cells there was a bed with a mattress of mattresses and straw and coarse woolen blankets without a pillow and a small table.

The walls showed some paintings on a religious theme or a wooden cross, since the symbols referring to faith were represented in the mural painting of the corridors of the cloister, the depths room and the refectory. A very important part were the libraries that were formed inside the convents, both as support for the study of the religious, and for their pastoral action. The three orders made great efforts to provide the convents with essential books for pastoral life and teaching. The subjects that were recommended were the Holy Bible, canon law and preaching books, to name a few.

As for the friars' health, it must have been good. The data from the conventual books indicate that they lived to be 60 or 70 years old, despite the unsanitary conditions of the time. Personal hygiene was relative, the bathroom was not routinely used, and in addition, they were frequently in contact with the population that suffered from contagious diseases such as smallpox and typhus, hence the existence of hospitals and infirmary for the friars. There were apothecaries with remedies based on medicinal herbs, many of which were cultivated by them in the garden.

Death was the final act of a religious who had dedicated his entire life to God. This represented an event, both personal and community. The last resting place of the friars was usually the convent in which they had lived. They were buried in the place chosen by them in the convent or in the one that corresponded to their religious hierarchy.

The functions of the New Spain convents and the missionaries were very different from those of the Europeans. Above all they served as places of indoctrination and catechetical instruction. In the 16th century they were centers of culture because the friars dedicated a large part of their days to evangelizing and educating. They were also architects and masters of many trades and arts and were in charge of drawing towns, roads, hydraulic works and cultivating the land with new methods. For all these tasks they used the help of the community.

The friars participated in the election of civil authorities and organized, to a large extent, the life of the populations. In synthesis, his work and daily life speaks of an interior, simple and unified faith, focused on the essence rather than on superficiality, because although daily life was marked by an iron discipline, each friar lived and communicated with himself and with the population like any human being.