Oh Malinalli, if they only knew! If they could see you that morning of March 15, 1519 when the Lord of Potonchán gave you, along with nineteen fellow slaves, to that bearded and sweaty foreigner, to seal the pact of friendship.

And she was hardly a girl, naked except for the shell of purity hanging from her waist and the loose black hair covering her shoulders. If they knew the fear you felt at how tremendous it was to leave, who knows where, with those strange men with incomprehensible tongues, strange clothes, machines with mouths of fire, thunderous, and animals so huge, so unknown, that it was believed at first that the strangers riding on them were double-headed monsters; the anguish of climbing those floating hills, of being at the mercy of those beings.

Once again you changed hands, it was your fate as a slave. Tamañita, your parents sold you to the Pochtec merchants, who took you to Xicalango, "the place where the language changes," to be resold. You no longer remember your first master; you do remember the second, the lord of Potonchán, and the watchful eye of the master of the slaves. You learned the Mayan language and to respect the gods and serve them, you learned to obey. You were one of the most beautiful, you got rid of being offered to the god of rain and being thrown to the bottom of the sacred cenote.

That hot morning in March you are comforted by the words of the chilam, the divine priest: "You will be very important, you will love until your heart breaks, ay del Itzá Brujo del Agua ...". It comforts you to have companions, the curiosity of the fourteen or fifteen years helps you, because nobody knows the date of your birth, or the place. Just like you, we only know that you grew up in the lands of Mr. Tabs-cob, mispronounced by strangers like Tabasco, in the same way as they changed the name to the town of Centla and named it Santa María de la Victoria, to celebrate the triumph.

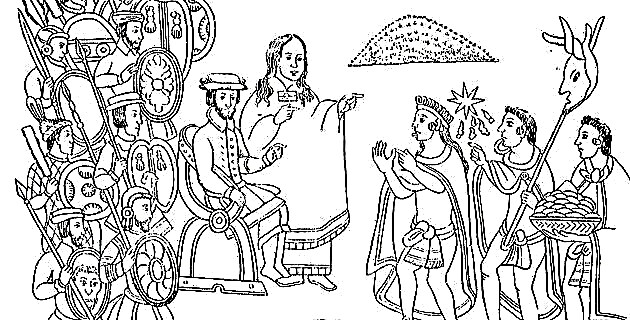

What were you like, Malinalli? You appear on the canvases of Tlaxcala, always dressed in a huipil and with your hair down, always next to Captain Hernando Cortés, but those paintings, just drawings, do not give us a clear idea of your features. It is Bernal Díaz del Castillo, a soldier from Cortés, who will make your spoken portrait: “she was good-looking and intrusive and outgoing… let's say how doña Marina, being a woman of the earth, what a manly effort she had… we never saw weakness in her, but much greater effort than a woman's ...

Tell me, Malinalli, did you really become a Catholic in that month that the journey lasted until you reached the coast of Chalchicoeca, today Veracruz? Jerónimo de Aguilar, taken prisoner in 1517 when the Mayans defeated Juan de Grijalva, was the one who translated Fray Olmedo's words into Mayan, and thus they let you know that your venerated gods were false, they were demons, and that there was only one unique god. but in three people. The truth is that the Spaniards were urged to baptize you, since he was excommunicated who slept with a heretic; That's why they poured water on your head and even changed your name, from then on you would be Marina and you should cover your body.

Was your first love Alonso Hernández de Portocarrero, to whom Cortés gave you? Only three months you were his; As soon as Cortés realized, upon receiving Motecuhzoma's ambassadors, that the only one who spoke and understood Nahuatl was you, he became your lover and put Juan Pérez de Arteaga as his escort. Portocarrero set sail for the Spanish kingdom and you would never see him again.

Did you love Cortés the man or were you drawn to his power? Were you pleased to leave the condition of slave and become the most important language, the key that opened the door of Tenochtitlan, because not only did you translate words but also explained to the conqueror the way of thinking, the ways, the Totonac, Tlaxcala beliefs and mexicas?

You could have settled for translating, but you went further. There in Tlaxcala you advised to cut off the spies' hands so that they would respect the Spaniards, there in Cholula you warned Hernando that they planned to kill them. And in Tenochtitlan you explained the fatalism and doubts of Motecuhzoma. During the Sad Night you fought alongside the Spanish. After the fall of the Mexica empire and the gods, you had a son by Hernando, Martincito, just when his wife Catalina Xuárez arrived, who would die a month later, in Coyoacan, perhaps murdered. And you would leave again, in 1524, on the Hibueras expedition, leaving your child in Tenochtitlan. During that expedition, Hernando married you to Juan Jaramillo, near Orizaba; From that marriage your daughter María would be born, who years later would fight the inheritance of her “father”, since Jaramillo inherited everything from the nephews of his second wife, Beatriz de Andrade.

Later, with deception, Hernando would take Martin away from you to send him as a page to the Spanish court. Oh, Malinalli, did you ever regret giving Hernando everything? How did you die, stabbed in your house on Moneda Street one morning on January 29, 1529, according to Otilia Meza, who claims to have seen the death certificate signed by Fray Pedro de Gante, so that you would not testify in against Hernando in the trial that was made? Or did you die of the plague, as your daughter declared? Tell me, does it bother you that you are known as Malinche, that your name is synonymous with hatred of what is Mexican? What does it matter, right? Few were the years that you had to live, much what you achieved in that time. You lived loves, sieges, wars; you participated in the events of your time; you were the mother of miscegenation; you are still alive in Mexican memory.