In the last decades of the last century, due to the importance that ancient history acquires in the moments in which the national conscience is politically programmed, the revaluation of the pre-Hispanic past of Mexico occurs.

This review and subsequent enhancement of past events, and especially of the time before the European conquest of our country, is the result of various cultural enterprises that bear fruit at this time.

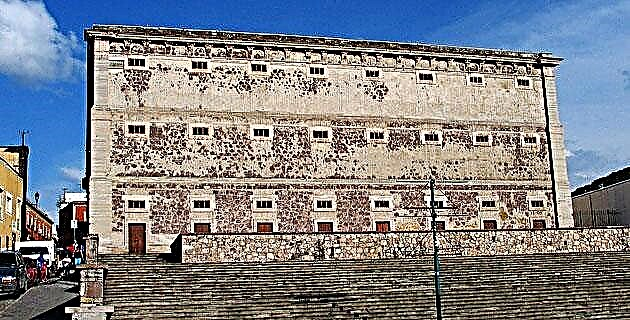

First of all, the importance of the National Museum should be highlighted; This, from its installation in the beautiful palace of the time of Felipe V, located in the streets of La Moneda, Historic Center of the Mexican capital, became a repository of the numerous archaeological and historical objects that had been rescued from the incuria; in addition to those that were donated by individuals and those that as a product of academic interest were received from distant regions, excavated by scientific commissions of that time.

In this way, the educated public and the curious admired the monuments of Mexican antiquity, of which their hidden meaning was gradually being discovered. Another element that contributed to the dissemination of the indigenous past was the publication of some monumental historical works that made reference to the pre-Hispanic era, as mentioned by Fausto Ramírez, who points out among the main works the first volume of Mexico through the centuries , whose author was Alfredo Chavero, Ancient History and the Conquest of Mexico, by Manuel Orozco y Berra, and the interesting and well illustrated articles on archaeological themes that enriched the Anaies of the National Museum. On the other hand, the old chronicles and stories and codices that informed readers about indigenous peoples and their most significant plastic expressions had already been edited.

According to specialists in 19th century Mexican art, the State undertook an ideological program that required a set of artistic works to support its government plans, for this reason it encouraged the students and teachers of the Academia de San Carlos to to participate in the creation of works whose themes had a precise reference to our nation and to make a visual account of some of the most significant episodes in history that little by little was acquiring official character. The best known pictorial compositions are the following: Fray Bartolomé de las Casas, by Félix Parra, The Senate of Tlaxcala and the Discovery of pulque, among others.

For Ida Rodríguez Prampolini ”The great paintings on an indigenous theme painted in the last quarter of a century by artists from the academy, corresponded more to the enlightened thought of the Creoles who achieved independence than to the mestizos who, as a class in conflict, they had come to power after the reform wars and the heroic deeds of the liberals around Benito Juárez. The Creole group that came to power after the war of independence felt the need to vindicate a glorious and dignified past in order to oppose it to the colonial past that they lived as alien and imposed ”. This would explain this peculiar pictorial production with an indigenous vein that, according to the same author, extends until the last decade of the 19th century and culminates in the painting by the artist Leandro Izaguirre El torture de Cuauhtémoc, painted in 1892, the date on which the Academia de San Carlos ends, practically, with the production of these historical allegories.

This necessary historical-artistic reference to the great official Mexican art of a pre-Hispanic character allows us to revalue the charming chrome-lithographs that illustrate the book entitled La Virgen del Tepeyac, by the Spanish Fernando Álvarez Prieto, printed in Barcelona by I. F. Parres y Cía. Editors.

The work consists of three thick volumes in which 24 plates are interspersed that give life to the heavy story, written very much in the style of those times; The theme, as its name indicates, is dedicated to recounting events and various stories around the apparitions of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Through its pages, the reader can learn about the ancient indigenous religion - there, of course, emphasis is placed on what the author considered aberrant: human sacrifice - and in some customs of the time, this is interwoven with adventure stories, betrayal and loves that today seem unimaginable - like those of a noble Aztec warrior with a Spanish woman and the daughter of a noble Tenochca with a peninsular knight.

We want to highlight the grace and color, as well as the ingenuity of these images that, as we can imagine, must have been the delight of the readers; The engravings have the lithography of Lavielle de Barcelona as their mark of production, in them it can be seen that various artists with different mastery of the trade intervened, some of them show great ingenuity. From the great group we have highlighted those whose pre-Hispanic theme immediately refers to an idealization of the ancient history of Mexico and in particular to the events immediately after the European conquest of the country. These images have points of convergence with the large-format oil paintings that we have mentioned above.

On the one hand, there are those that refer to the fictional characters in the play: the indigenous princess, the "cruel" priest, the intrepid young man and the noble warrior. His clothes are more like the costumes of a theatrical play: the eagle warrior's costume is extremely operatic, the wings of the bird of prey, imagined of cloth, move to the rhythm of his severe attitude, and what about the priest's clothing, tunic and long skirt, as befitted the clothing of the actors of the works of the last century.

The scenography places the characters in an unreal city, in which Mayan and Mixtec decorative elements are taken liberally and without greater knowledge of archaeological sites and a fantastic architecture is interwoven with them in which the buildings display decorative elements that somehow In this way we could interpret them as frets or almost frets, in addition to the so-called "false lattices" that, we know, identify the Mayan buildings of the Puuc style.

Special mention should be made of the sculptural monuments and other ritual elements present in the compositions: in some cases the engraver had truthful information - sculptures and ceremonial vessels from the Aztec period - and thus copied them; in other cases he took as a pattern the images of the codices, to which he gave three-dimensionality. By the way, the same intention can be seen in the oil paintings of academic authors.

In the chromolithographies that relate true historical events, various ways of expressing them are appreciated; This is undoubtedly due to the different sources of information. The first example, in which the encounter between Moctezuma and the Spaniards is related, immediately leads to the subject dealt with by the Mexican baroque artists who painted the so-called "screens of the conquest" that decorated the houses of the conquerors, many of whom were sent to Spain. In the engraving, a character between Roman and aboriginal of the Amazon is given to the Lord of Tenochtitlan and his companions.

Regarding the martyrdom of Cuauhtémoc, the convergence in the composition used by Gabriel Guerra, as well as by Leonardo Izaguirre and our anonymous artist, is remarkable. He uses a huge feathered serpent's head that serves as a resting place for the tormented indigenous king. Surely, his source of inspiration was the corresponding engraving of the aforementioned volume of the book Mexico through the centuries, also published in Barcelona.

Finally, the delightful image of Quetzalcoatl's flight from Mexican lands stands out, which places the character in the city of Palenque - in the style of Waldeck's engravings - only immersed in an impossible desert landscape, witnessed by the numerous xerophytic plants, Among which could not be missing the maguey, from which the pulque with which Quetzalcoatl got drunk was extracted, the reason for the loss of his image of power.

Here Quetzalcoatl is a kind of Christian saint with long whitish hair and beards who wears a theatrical costume, very similar to that of a priest of old Judea, completely covered with the enigmatic crosses that made the first chroniclers imagine Quetzalcoatl as a a sort of Saint Thomas, half Viking, who tried, without success, before the Columbian voyages, to convert the Indians to Christianity.

In many of these nineteenth-century publications there are hidden treasures of graphics that delighted their readers and idealized the past that was reinterpreted: they condemned ancient peoples and justified the European conquest, or they exalted the bravery and martyrdom of their heroes at the hands of the Spanish conquistador.