The poster is probably the oldest and undoubtedly the most prominent public manifestation of graphic design. Any opinion on the evolution and prospects of the cartel is associated with industrial and commercial development.

Any institution or entity, when requesting the services of the poster to promote the consumption of a certain article in the market, the diffusion of shows, tourism or social orientation campaigns, exerts an influence on the existence of this graphic modality. In the film industry, posters have a very definite and certainly commercial purpose: to promote a film and to generate a large audience in theaters.

Of course, Mexico has not been the exception in this phenomenon, and since 1896, from the arrival of Gabriel Veyre and Ferdinand Bon Bernard - the envoys of the Lumière brothers, in charge of showing the cinematograph in this part of the Americas - A series of programs was ordered to be printed, mentioning the views and the theater in which they would be shown. The walls of Mexico City were populated with this propaganda, provoking great expectation and a spectacular influx in the building. Although we cannot attribute all the success of these functions to these mini-posters in the form of a lantern, we do recognize that they fulfilled their basic task: to publicize the event. However, it is still surprising that posters closer to the concept that we have of them were not used then, since at that time, in Mexico, for the announcement of theater functions - and in particular those of the magazine theater, genre of great tradition in the capital - it was already relatively common to use images on promotional posters similar to those made by Toulousse-Lautrec, in France, for similar events.

A small first boom of the poster in Mexican cinema would come from 1917, when Venustiano Carranza - tired of the barbaric image of the country spread abroad due to the films of our Revolution - decided to promote the production of tapes that offered a totally different vision of Mexicans. For this purpose, it was decided not only to adapt the then very popular Italian melodramas to the local environment, but also to imitate their forms of promotion, including, although only for when the film was shown in other countries, the drawing of a poster in which the image of the long-suffering heroine of the story was privileged to attract the attention of the spectators. On the other hand, in the rest of the first decade of the twentieth century and throughout the twenties, the element normally used for the diffusion of the few films produced in those times would be an antecedent of what today is known as photomontage , cardboard or lobby card: a rectangle of approximately 28 x 40 cm, in which a photograph was placed and the credits of the title to be promoted were painted on the rest of the surface.

In the 1930s, the poster began to be considered as one of the essential accessories for the promotion of films, since film production began to be more constant since the making of Santa (Antonio Moreno, 1931). At that time the film industry in Mexico began to take shape as such, but it would not be until 1936, when Allá en el Rancho Grande (Fernando de Fuentes) was filmed, when it was consolidated. It should be noted that this film is considered one of the milestones in the history of Mexican cinema, since due to its global significance, it allowed the country's producers to discover a work scheme and a nationalist film style that paid off for them.

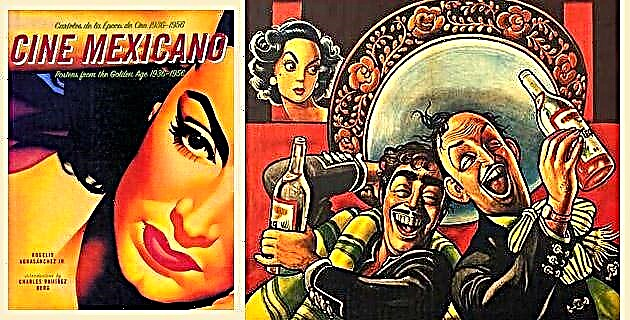

THE POSTER OF THE GOLDEN AGE OF MEXICAN CINEMA

Continuing this line of work with few variations, in a short time the Mexican film industry became the most important Spanish-speaking industry. With that initial success capitalized on its full potential, a star system was developed in Mexico, similar to the one that worked in Hollywood, with influence throughout Latin America, an area in which the names of Tito Guízar, Esther Fernández, Mario Moreno Cantinflas, Jorge Negrete or Dolores del Río, in its first stage, and Arturo de Córdova, María Félix, Pedro Armendáriz, Pedro Infante, Germán Valdés, Tin Tan or Silvia Pinal, among many others, already meant a guarantee of box office success. Since then, in what various specialists called the Golden Age of Mexican cinema, the design of the poster also experienced a golden age. Its authors, certainly, had more factors in their favor to carry out their work; were implementing, without a code or predetermined patterns or lines of work, a series of characteristics duly detailed in the highly recommended book Carteles de la Época de Oro del cine Mexicano / Poster Art from the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema, by Charles Ramírez-Berg and Rogelio Agrasánchez, Jr. (Archivo Fílmico Agrasánchez, Imcine and UDG, 1997). In those years, by the way, the posters were rarely signed by their authors, since most of these artists (renowned painters, cartoonists or cartoonists) considered these works as purely commercial. Notwithstanding the foregoing, thanks to the work of specialists such as the aforementioned Agrasánchez, Jr., and Ramírez-Berg, as well as Cristina Félix Romandía, Jorge Larson Guerra (authors of The Mexican Film Poster, edited by the National Cinemas for more than 10 years, for a long time the only book on the subject, currently out of print) and Armando Bartra, is that they have managed to transcend names such as Antonio Arias Bernal, Andrés Audiffred, Cadena M., José G. Cruz, Ernesto El Chango García Cabral, Leopoldo and José Mendoza, Josep and Juanino Renau, José Spert, Juan Antonio and Armando Vargas Briones, Heriberto Andrade and Eduardo Urzáiz, among many others, as those responsible for many of those wonderful works applied to the posters of the films produced between 1931 and 1960.

DECADE AND RENEWAL OF THE POSTER

After this period of splendor, along with what is experienced in the panorama of the film industry in much of the sixties, the design of the movie poster in Mexico experiences a terrible and profound mediocrity, in which except for a few Exceptions such as some of the works made by Vicente Rojo, Alberto Isaac or Abel Quezada, in general fell into apathy and yellowishness with lavish designs in blood red, scandalous calligraphies and extravoluptuous figures of women who tried to represent the main actresses. Of course, also in those years, especially at the end of this decade, as in other aspects of the history of Mexican cinema, a new generation of designers was gestating, who later, together with the integration of plastic artists from With greater experience in other disciplines, they would renew the concepts of the poster design by daring to use a series of novel forms and concepts.

Indeed, when the professional cadres of the Mexican film industry were renewed, in most of its aspects, the elaboration of the posters was no exception. From 1966-67, posters that integrated, as their main graphic element, a large size representative photograph of the theme addressed by the film, and later a typeface of very characteristic and unique shapes was added to it. And it is not that photos had not been used in the posters, but the main difference was that in this modality, what was embedded in those posters were only the stylized photos of the actors who intervened in the film, but apparently this message already it had lost its old impact on the public. Do not forget that the star system was already a thing of the past at that time.

Another style that soon became familiar was the minimalist, in which, as its name implies, an entire image was developed from the minimal graphic elements. It sounds simple but it definitely wasn't, since to reach its final conception it was necessary to combine a series of ideas and concepts concerning the themes of the film, and take into account the commercial guidelines that would allow offering an attractive poster whose basic function would fulfill the goal of attracting people to cinemas. Fortunately, on numerous occasions this goal was more than fulfilled, and proof of this are the countless creations, above all, of the most prolific designer of that time, who unquestionably marked a time with his unmistakable style: Rafael López Castro.

THE TECHNOLOGICAL REVOLUTION IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE POSTER

In recent times, the mercantile and social impact objectives, with some small variations, are those that have prevailed in Mexico as far as the conception of cinematographic posters is concerned. Of course, we must point out that with the great technological revolution that we have experienced, especially for about 10 years, one of the areas that has benefited the most in this regard has been design. The new softwares that emerge and are being renewed at an inordinate speed have given designers impressive work tools that, in addition to greatly facilitating their work, have opened up a vast panorama in which there is practically no idea or desire that they cannot perform. So much so that now they offer us as a result a series of beautiful, audacious, disturbing or indescribable images, which invariably catch our attention, either for better or for worse.

Notwithstanding the above, it is fair to insist that all this technology paraphernalia, put at the service of designers, is precisely a working tool and not a substitute for their talent and inspiration. That will never happen, and as irrefutable proof is that names of Rafael López Castro, Vicente Rojo, Xavier Bermúdez, Marta León, Luis Almeida, Germán Montalvo, Gabriela Rodríguez, Carlos Palleiro, Vicente Rojo Cama, Carlos Gayou, Eduardo Téllez, Antonio Pérez Ñico, Concepción Robinson Coni, Rogelio Rangel, Patricia Hordóñez , Bernardo Recamier, Félix Beltrán, Marta Covarrubias, René Azcuy, Alejandro Magallanes, Ignacio Borja, Manuel Monroy, Giovanni Troconni, Rodrigo Toledo, Miguel Ángel Torres, Rocío Mireles, Armando Hatzacorsian, Carolina Kerlow and others, many others, are always the reference names when talking about the Mexican cinema poster of the last thirty years. To all of them, to all the others mentioned above, and to anyone who has made a poster for Mexican films of all time, may this brief article serve as a small but well-deserved recognition for having forged an extraordinary cultural tradition of undeniable personal and national personality. In addition to having fulfilled its main mission, since on more than one occasion, victims of the spell of its images, we went to the cinema only to realize that the poster was better than the film. No way, they did their job, and the poster fulfilled its objective: to catch us with its visual spell.

Source: Mexico in Time No. 32 September / October 1999