According to Germán Arciniega, the word pichilingue is derived from the English speak in English, which was the order given to the frightened natives of the Pacific coast, who, in addition to being assaulted and outraged, supposedly had to know the language of Shakespeare.

A second definition of the term was provided by the eminent Sinaloan historian Pablo Lizárraga, who assures that it comes from Nahuatl and is derived from pichihuila, a variety of migrant duck that presents a rather clear appearance: its eyes and the feathers that surround them give the impression that it is a blonde bird.

It is not wrong to think that pirates, mostly Nordics, would be equally blond. The appearances of the pichilingues on the coastlines, generally in small coves with waters deep enough for them to anchor in them and in relatively protected sites, has led to the presence of beaches called pichilingues on some coasts of South America and, recurrently , in Mexico.

The third theory is equally valid. A large number of pirates - a generic name for the men who carried out this kind of activities - came from specifically in the 17th century, from the Dutch port of Vlissinghen. In sum, the origin of the word continues to be as elusive as the individuals to whom it referred, especially throughout the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

Having managed to penetrate the Pacific by circumnavigating the Strait of Magellan, conflicts soon began with the Spanish, owners of the so-called "Spanish lake", and the greed and enmity of the English and the Flemish. The first Dutch pichilingue to cross this ocean was Oliver van Noort in the year 1597. Van Noort was a tavern keeper, a former seaman, who with his own fleet with four ships and 240 men carried out atrocious looting and pillaging in the South American Pacific. but it did not reach the shores of New Spain. His end was possibly what he deserved: he died by hanging in Manila.

In 1614 news reached New Spain that Dutch danger was approaching. In August of that year, the East India Company had sent four large privateer ships (that is, they had "marquees" from their governments) and two "jachts" on a "trade mission" around the world. The peaceful mission was reinforced by the strong weaponry on board the ships headed by the Groote Sonne and the Groote Mann.

At the head of this mission was the prestigious admiral –prototype of the privateer– Joris van Spielbergen. The refined navigator, born in 1568, was a skilled diplomat who liked his flagship to be elegantly furnished and stocked with the best wines. When he ate, he did so with the onboard orchestra and a choir of sailors as the musical background. His men wore magnificent uniforms. Spielbergen had a special commission from the States General and from Prince Maurice Orange. It is very likely that among the secret orders was to capture a galleon. The illustrious pichilingue navigator made his untimely appearance on the shores of New Spain in late 1615.

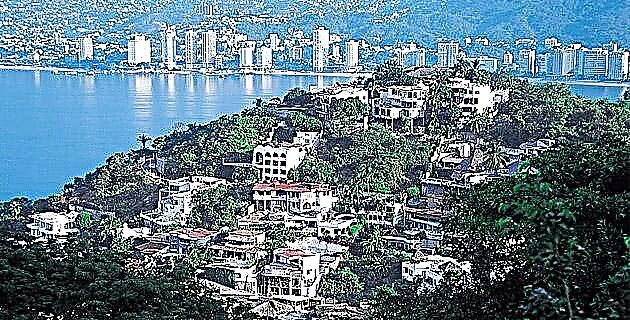

After tremendous battles against the Spanish navy in the South American Pacific, in which their fleet was practically untouchable, with few human losses and their ships barely damaged, the pichilingues headed north; however, New Spain was ready waiting for the Dutch. In June 1615, Viceroy Márques de Guadalcázar ordered the mayor of Acapulco to strengthen the port's defenses with trenches and cannons. A detachment of knights voluntarily joined forces to fight the enemy decisively.

IN FRONT OF ACAPULCO

On the morning of October 11, the Dutch fleet dawned in front of the entrance to the bay. Brazenly penetrating it, the ships anchored before the makeshift fort after noon. They were greeted with a salvo of cannon shots that had little effect. Furthermore, Spielbergen was determined to destroy the village if necessary, for it needed food and water. At last a truce was declared and Pedro Álvarez and Francisco Méndez, who had served in Flanders, got on board so they knew the Dutch language.

Spielbergen offered in exchange for much-needed supplies, to free the prisoners they had taken off the coast of Peru. An agreement was reached and, curiously, for a week, Acapulco became a lively meeting place between pichilingues and Spaniards. The commander was received on board with honors and a parade of perfectly uniformed sailors, while the young son of Spielbergen spent the day with the mayor of the port. A civilized encounter that would contrast with the subsequent adventures of the Dutchman on the shores north of Acapulco. Spielbergen had a plan of the port made in advance.

The viceroy, fearing that the Manila Galleon that was about to arrive would be arrested, sent no less than Sebastián Vizcaíno with 400 men to protect the ports of Navidad and Salagua, and the governor of Nueva-Vizcaya sent another detachment to the coast of Sinaloa under the orders of Villalba, who had precise instructions to avoid enemy landings.

Along the way, Spielbergen seized the pearl ship San Francisco, then changed the name of the ship to Perel (pearl). In a next landing in Salagua, Vizcaíno waited for the pichilingues and after a battle that was not very favorable to the Spanish, Spielbergen withdrew to Barra de Navidad, or more possible to Tenancatita, where he spent five days off with his men in the pleasant bay. Vizcaíno, in his report to the viceroy, makes mention of the heavy losses of the enemies and as proof sends him the ears that he had cut off a pichilingue. Vizcaíno described some of the “pichilingas” he had taken prisoner as “young and upright men, some of them Irish, with big curls and earrings”. The Irish had been lured into Spielbergen's army, believing they were on a peace mission.

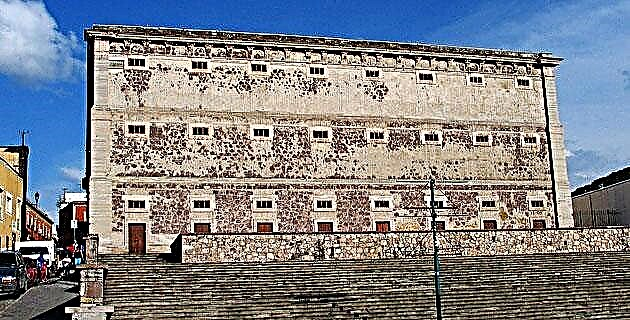

At Cape Corrientes, Spielbergen decided not to waste any more time in the waters of New Spain and headed south. A few days later, the Manila Galleon passed the Cape. Spielbergen died in poverty in 1620. The much-needed construction of Fort San Diego in Acapulco would begin shortly after to better protect the port from pirate attacks.

AGAINST THE SPANISH EMPIRE

In 1621, a supposed truce between Holland and Spain came to an end. The Dutch were prepared to send the most powerful fleet to appear in the Pacific, known as the Nassau Fleet - "Nasao" - by the prince, their sponsor. Its true purpose was to annihilate the Spanish preponderance in this ocean. It would also seize the rich galleons and plunder the cities. The fleet left Holland in 1623 loaded with 1626 pichilingues commanded by the famous admiral Jacobo L. Hermite, who died on the coasts of Peru. Then Vice Admiral Hugo Schapenham assumed command, who bypassed the Acapulco Fort, because the Castilian did not accept the pirate's pleas that lacked water and supplies, so the great fleet had to move away towards the beach, which today known as Pichilingue, to stock up.

As there was a detachment of Spaniards waiting for them, the Dutch had to raise anchor towards Zihuatanejo where they waited uselessly for the “long-awaited prey”: the elusive galleon. However, the supposedly invincible Nassau Fleet failed ignominiously, had boundless hopes and invested millions of florins. The era of the pichilingues supposedly came to an end with the Peace of Westphalia in 1649, however, the term pichilingue was coined forever in the history of piracy and in the Spanish vocabulary.

The Pacific ceased to be, according to the chronicler Antonio de Robles (1654-172).

1685: ”November, 1st. This day new came from being in sight the enemies with seven ships ”“ Monday 19. It came new from having seen sails by the coast of Colima of enemies and a prayer was played ”“ December 1st. Mail came from Acapulco with news of how the enemies went to Cape Corrientes and that they tried to enter the port twice and were rejected ”.

1686: "February 12. New wine from Compostela having sent people out and made meat and water, taking four or six families: they ask for ransom."

1688: "November 26. New wine as the enemy entered Acaponeta and took forty women, a lot of money and people and a father from the Company and another from La Merced."

1689: “May. Sunday 8. New news came about how the English cut off the ears and noses of Father Fray Diego de Aguilar, urging the rescue of our people who would otherwise die ”.

The chronicler refers in this case to the English pichilinque-buccaneers Swan and Townley, who ravaged the northwest coast of New Spain in vain waiting for a galleon.

The Pacific beaches, its ports and fishing villages were constantly besieged by the Pichilingues, but they did not achieve the desired goal of catching a Manila Galleon until the following century. Even though they got loot, they also got big disappointments. When trapping the Santo Rosario ship that carried the holds full of silver bars, the English believed that it was tin and threw them overboard. One of them kept an ingot as a souvenir. Returning to England, he discovered that it was solid silver. They had thrown more than 150 thousand pounds of silver into the sea!

Cromwell, the famous “Coromuel,” who established his headquarters between La Paz and Los Cabos, in Baja California, stands out among the pichilingues who left the greatest mark on a specific portion of New Spain. His name has remained in the wind that commemorates him, “the coromuel”, which he used to sail and hunt down some rich galleon or pearl ship. His stronghold was the beach that bears the name of Coromuel, near La Paz.

Cromwell left one of his flags or "joli roger" in this remote and magical region. Today it is in the Museum of Fort San Diego. Coromuel, the man, mysteriously disappeared, not his memory.