I invite you to undertake an imaginary journey through the very noble and loyal Mexico City as it was in the 18th and 19th centuries. As we pass we will find everywhere a display of colors and textures in the attire of the inhabitants of the capital.

Immediately we will go to the field, the real roads and the sidewalks will take us to contemplate the landscapes of the different regions, we will enter the towns, the haciendas and the ranches. Men and women, peons, muleteers, peasants, shepherds or landowners dress in Creole fashion, although according to their race, sex and social condition.

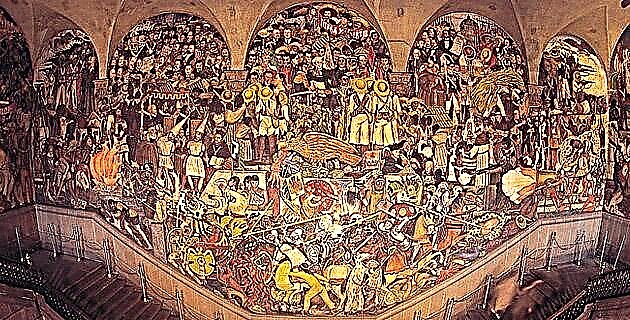

This imaginary journey will be possible thanks to the writers, painters and cartoonists who knew how to capture what they saw of Mexico at that time. Baltasar de Echave, Ignacio Barreda, Villaseñor, Luis Juárez, the Rodríguez Juárez, José Páez and Miguel Cabrera are part of the plethora of artists, Mexicans and foreigners, who portrayed the Mexican, his way of being, living and dressing. But let us remember another wonderful form of traditional art, the caste paintings, which illustrated, not only the people who resulted from the mixtures of races, but the environment, the dress and even the jewels that they wore.

In the 19th century, shocked by the "exotic" world described by Baron Humboldt, William Bullock and Joel. R. Poinsett, innumerable illustrious travelers arrived in Mexico, among them the Marquesa Calderón de la Barca and others, such as Linati, Egerton, Nevel, Pingret and Rugendas who alternated with the Mexicans Arrieta, Serrano, Castro, Cordero, Icaza and Alfaro in their eagerness to portray Mexicans. Writers as popular as Manuel Payno, Guillermo Prieto, Ignacio Ramírez –el Nigromante–, José Joaquín Fernandez de Lizardi and later Artemio de Valle Arizpe left us very valuable pages of the daily events of those times.

Viceregal ostentation

Let's go to the Plaza Mayor on a Sunday morning. On one side appears, accompanied by his family and his entourage, Viceroy Francisco Fernández de la Cueva, Duke of Albuquerque. In an elegant carriage brought from Europe he comes to hear mass in the Cathedral.

Gone are the sober dark suits of the late sixteenth century whose only luxury was the white ruffles. Today the French-style fashion of the Bourbons prevails. The men wear long, curly and powdered wigs, velvet or brocade jackets, Belgian or French lace collars, silk trousers, white stockings, and leather or cloth footwear with colorful buckles.

The ladies of the early eighteenth century wear fitted silk or brocade dresses with pronounced necklines and wide skirts, under which the frame of hoops called by them "guardainfante" is placed. These intricate costumes feature pleats, embroidery, gold and silver thread inlays, strawberry trees, rhinestones, beads, sequins, and silk ribbons. Children dress up in replicas of their parents' costume and jewelry. The costumes of the servants, pages and coachmen are so ostentatious that they provoke laughter from passersby.

Rich Creole and mestizo families copy the dresses of the viceregal court to wear them at parties. Social life is very intense: meals, snacks, literary or musical evenings, gala saraos and religious ceremonies fill the time of men and women. The Creole aristocracy is present, not only in clothing and jewelry, but also in architecture, transportation, art in its various manifestations and in all everyday objects. The high clergy, military, intellectuals and some artists alternate with "the nobility" who in turn have slaves, servants and ladies in waiting.

In the upper classes the attire changes with events. Europeans dictate fashion, but Asian and native influences are definitive and result in exceptional garments like the shawl, which many researchers say is inspired by the Indian saree.

A separate chapter deserve the products of the East coming in the ships. Silks, brocades, jewels, fans from China, Japan and the Philippines are widely accepted. The silk embroidered Manila shawls with long fringes equally captivate the residents of New Spain. Thus we see that the Zapotec women of the Isthmus and the Chiapanecas recreate the designs of the shawls on their skirts, blouses and huipiles.

The middle class wears simpler clothes. Young women wear light garments in strong colors, while older women and widows wear dark colors with high necks, long sleeves and a mantilla held up by a tortoiseshell comb.

Since the middle of the 18th century, fashion has been less exaggerated in men, wigs are shortened and jackets or vests are more sober and small. Women have a preference for ornate garments, but now the skirts are less wide; Two watches are still hanging from their waists, one that marks the time of Spain and the other that of Mexico. They usually wear tortoiseshell or velvet “chiqueadores”, often inlaid with pearls or precious stones.

Now, under the mandate of Viceroy Conde de Revillagigedo, tailors, seamstresses, trousers, shoemakers, hats, etc., have already organized into unions to regulate and defend their work, since a large part of the outfits are already made in the New Spain. In the convents, the nuns make lace, embroider, wash, starch, gun, and iron, in addition to religious ornaments, clothing, home clothes and robes.

The suit identifies whoever wears it, for that reason a royal edict has been issued prohibiting the hat and the cape, since the muffled men are usually men of bad behavior. Blacks wear extravagant silk or cotton dresses, long sleeves and bands at the waist are customary. The women also wear turbans so exaggerated that they have earned the nickname "harlequins". All his clothes are brightly colored, especially red.

Winds of renewal

During the Enlightenment, at the end of the 17th century, despite the great social, political and economic changes that Europe began to experience, the viceroys continued to lead a life of great waste that would influence the popular mood during Independence. The architect Manuel Tolsá, who, among other things, finished the construction of the cathedral in Mexico, comes dressed in the latest fashion: a white tufted waistcoat, a colored woolen cloth jacket and a sober cut. The ladies' costumes have Goya influences, they are sumptuous, but dark in color with an abundance of lace and strawberry trees. They cover their shoulders or their head with the classic mantilla. Now, the ladies are more "frivolous", they smoke continuously and even read and talk about politics.

A century later, the portraits of the young women who were going to enter the convent, who appear elegantly dressed and abundant jewels, and the heiresses of the indigenous chiefs, who have themselves portrayed with profusely adorned hipiles, remain as testimony of women's clothing. in the Spanish way.

The busiest streets in Mexico City are Plateros and Tacuba. There, exclusive shops display suits, hats, scarves and jewelry from Europe on the sideboards, while in the "drawers" or "tables" located on one side of the Palace, fabrics of all kinds and lace are sold. At El Baratillo it is possible to get second-hand clothes at low prices for the impoverished middle class.

Age of austerity

At the beginning of the 19th century, women's clothing changed radically. Under the influence of the Napoleonic era, the dresses are almost straight, with soft fabrics, high waists and “balloon” sleeves; short hair is tied up and small curls frame the face. To cover the wide neckline, the ladies have lace scarves and scarves, which they call “modestín”. In 1803, the Baron de Humboldt wears the latest fashion trends: long trousers, a military-style jacket and a wide-brimmed bowler hat. Now the laces of the men's suit are more discreet.

With the war of independence of 1810 come difficult times in which the wasteful spirit of yesteryear has no place. Perhaps the only exception is the ephemeral empire of Agustín de Iturbide, who attends his coronation with an ermine cape and a ridiculous crown.

The men have short hair and wear austere suits, tailcoats or frock coats with dark wool trousers. The shirts are white, they have a high neck finished in bows or plastrones (wide ties). Proud gentlemen with beards and mustaches wear the straw hat and cane. This is how the characters of the Reformation dress, this is how Benito Juárez and the Lerdos de Tejada portrayed themselves.

For women, the romantic era is beginning: dresses waisted with wide silk, taffeta or cotton skirts are back. The hair gathered in a bun is as popular as shawls, shawls, shawls and scarves. All ladies want a fan and an umbrella. This is a very feminine fashion, elegant, but still without great extravagances. But modesty does not last long. With the arrival of Maximiliano and Carlota, the saraos and ostentation return.

The "people" and its timeless fashion

We now visit the streets and markets to get closer to the “people of the town”. The men wear short or long pants, but there is no shortage of people who only cover themselves with a loincloth, in addition to simple shirts and white blanket huipiles, and those who do not go barefoot wear sandals or boots. If their economy allows it, they wear wool jumpers or sarapes with different designs depending on the region of their origin. Petate, felt and "donkey belly" hats abound.

Some women wear entanglement –a rectangular piece woven on a loom fastened at the waist with a sash or girdle–, others prefer the straight skirt made of handmade blanket or twill, also fastened with girdle, round neckline blouse and “balloon” sleeve. Almost all wear shawls on the head, on the shoulders, crossed on the chest or on the back, to carry the baby.

Under the skirt they wear a cotton skirt or bottom trimmed with hook or bobbin lace work. They are parted in the middle and braids (on the sides or around the head) that end in bright colored ribbons. The use of embroidered or embroided huipiles that they wear loose, in the pre-Hispanic way, is still very common. The women are brunettes with dark hair and eyes, they are distinguished by their personal hygiene and their large earrings and necklaces of coral, silver, beads, stones or seeds. They make their outfits themselves.

In the countryside, the men's costume has been modified over time: the simple indigenous costume is transformed into the ranch outfit of long pants with chaps or suede breeches, a blanket shirt and wide sleeves and a short cloth or suede jacket. Among the most notable are some silver buttons and the ribbons that adorn the costume, also made with leather or silver.

The caporales wear chapareras and suede cotonas, proper to withstand the rough country tasks. Leather boots with laces and a mat, soy or leather hat –different in each region– complete the outfit of the industrious country man. The Chinacos, famous rural guards of the nineteenth century, wear this outfit, a direct antecedent of the charro costume, famous throughout the world and the hallmark of the "authentically Mexican" man.

In general, the dresses of the "people", the less privileged classes, have changed very little over the centuries and garments whose origin is lost in time have survived. In some regions of Mexico, pre-Hispanic dresses are still used or with some modality imposed by the Colony. In other places, if not on a daily basis, they are worn at religious, civic and social festivals. They are handmade garments, of complex elaboration and great beauty that are part of popular art and constitute a source of pride, not only for those who wear them, but for all Mexicans.

Source: Mexico in Time No. 35 March / April 2000