In the state of Chihuahua, on the western bank of the Casas Grandes River, south of the town of the same name, is this pre-Hispanic settlement described by Spanish chroniclers as a “great city [with] buildings that seemed to have been built by the ancient Romans ... "Find out!

Until relatively recently, the Mexican northwest had been an unknown land for anthropologists and archaeologists, to the extent that perhaps there is no other place so unknown in North America. This immense expanse of deserts, valleys, and mountains was shared by Paquimé with other important population centers in the southern United States, such as Chaco and Aztec in New Mexico, Mesa Verde in southern Colorado, and Snaketown in southeastern Arizona. culture that Paul Kirchhoff baptized as Oasisamerica.

Around 1958, the research carried out by Dr. Charles Di Peso, with the support of the Amerind Foundation, made it possible to establish a chronology for the place, made up of three basic periods: the Old period (10,000 BC-1060 AD); the Middle period (1060-1475), and the Late period (1475-1821).

In the region, the Old period is a long road of cultural evolution. It is the time of hunting and gathering, which kept men searching for food through these vast areas for about 10,000 years, until they began to practice the first crops, around 1000 BC. Later, based on a tradition of earthen architecture that developed in northwestern Mexico and the southwestern United States, Paquimé arises, with small villages of five or more semi-underground houses and a large house, the ritual space, surrounded of patios and squares. These are the times when the exchange of shells and turquoise that merchants brought from the shores of the Pacific Ocean and from the mines of southern New Mexico, respectively, began to take place. Times when the cult of Tezcatlipoca was born in Mesoamerica.

Later, very early during the Middle Period, a group of leaders who had assumed control of water management, and who had become related through pacts and marriage alliances with the most important priests, decided to establish a ritual space that at the same time dessert would become the center of power of the regional system. The development of agricultural techniques fueled the growth of the city, and in a process that took nearly three hundred years, one of the most important social organization systems in northwestern Mexico was built, flourished and collapsed.

Paquimé amalgamated elements of northern cultures (for example, the Hohokam, the Anazasi and the Mogollón) in his daily life, such as earthen architecture, palette-shaped doors and the cult of birds, among others, with elements of southern cultures, particularly the Toltecs of Quetzalcóatl, such as the ball game.

The territorial sovereignty of Paquimé depended fundamentally on the natural resources that its environment provided. Thus, it obtained the salt from the areas of the Samalayuca dune desert, which constituted its limit of influence towards the east; from the west, from the shores of the Pacific Ocean, came the shell for trade; to the north were the copper mines of the Gila River region, and to the south the Papigochi River. Thus, the term Paquimé, which in the Nahuatl language means "Big Houses", refers both to the city and to its specific cultural area, so that it includes the wonderful cave paintings of the Samalayuca area, which represent the first images of American thought. , the valley occupied by the archaeological zone and the caves with houses in the mountains, which are significant signs of the presence of man in these environments that are still so hostile today.

Among the technological developments that marked the evolutionary process of Paquimé we find the management of a hydraulic system. The set of ditches that supplied running water to the pre-Hispanic city of Paquimé began at the spring known today as the Ojo Vareleño, located five kilometers north of the city. The water was transported through canals, ditches, bridges, and dikes. even in the city itself there was an underground well, from which the residents obtained water during the times of siege.

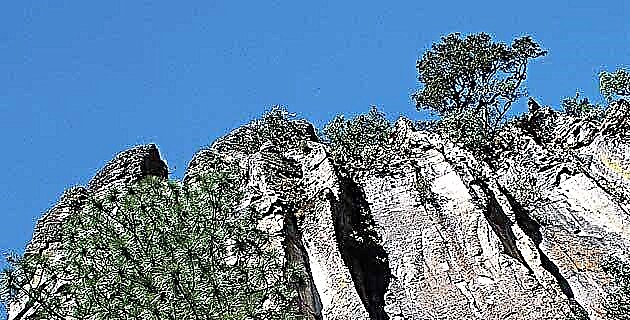

When Francisco de Ibarra explored the Casas Grandes valley in 1560, its chronicler wrote: “we found paved roads”, and since then many chroniclers, travelers and researchers have verified the existence of royal roads that cross the mountains of the Sierra Madre de Chihuahua and of Sonora, connecting not only the populations of the regional system but also the west with the northern highlands. Likewise, there is evidence of a long-range communication system across the highest mountain tops; These are circular constructions or with an irregular plan, spatially interconnected, which facilitated communication by means of mirrors or smokestacks. On one side of the city of Paquimé is the largest of these constructions, known as Cerro Moctezuma.

In the minds of the architects who designed and planned the city, the idea that function and environment determined form was always present. The city satisfied many demands of its inhabitants, including accommodation, food preparation, storage, reception, recreation, manufacturing workshops, macaw farms and the houses of priests, healers, mezcaleros, merchants, players. ball, warriors and leaders and sovereigns.

Paquimé was inscribed on the UNESCO world heritage list because its earthen architecture is a chronological marker in the development of the construction techniques of this unique architectural type; All the residences and spaces mentioned above are made with a construction technique that used beaten clay, poured into wooden molds and placed row after row, one on top of the other, until the expected height was reached.

Dr. Di Peso established that the city was planned to house about 2,242 individuals in a total of 1,780 rooms, which were aggregated into family groups, like apartments. Connected by corridors, forming a significant pattern of social organization within the city, these groups were independent of each other, despite the fact that the rooms were under the same roof. Over time the population increased and areas that were once public were transformed into housing; even several corridors were closed to turn them into bedrooms.

Some units were built during the early phases of the Middle Period and were later heavily modified. Such is the case of unit six, a family group located in the northern part of the central square, which began as a small group of independent rooms and later ended up annexed to the Casa del Pozo.

La Casa del Pozo is named for its underground well, the only one in the entire city. It is possible that this complex accommodated 792 people in a total of 330 rooms. This building of rooms, cellars, patios and closed squares had the largest number of archaeological objects specialized in the elaboration of shell artifacts. Its cellars contained millions of seashells of at least sixty different species, originating from the coasts of the Gulf of California, in addition to a pure rhyolite in chunks, turquoise, salt, selenite and copper, as well as a set of fifty vessels from the Gila River region, New Mexico.

This family group presented clear evidence of slavery, since inside one of its rooms that were used as warehouses, a vertical door was found that communicated to a collapsed room, whose height did not reach one meter, which contained innumerable pieces of shell and the remains of a human being inside, in a seated position, who was probably working the pieces at the time of the collapse.

Towards the south of the Casa de la Noria is the Casa de los Cranios, so called because in one of its rooms a mobile made with human skulls was found. Another small single-level family group is the House of the Dead, which was occupied by thirteen inhabitants. Archaeological evidence suggests that these people were specialists in death rituals, as their rooms contained a large number of individual and multiple burials. Containing offerings with ceramic drums and other archaeological objects as fetishes, these burials were associated with rituals in which the revered macaws were used.

The Casa de los Hornos, at the northern end of the city, is made up of a group of eleven single-level rooms. Due to the archaeological evidence found in the place, it is known that its inhabitants were dedicated to the production in large quantities of agave liquor, called "sotol", which was consumed in agricultural festivals. The construction is surrounded by four conical ovens embedded in the ground that were used to burn the heads of the agaves.

The Casa de las Guacamayas was probably the residence of what Father Sahagún called “feather merchants”, who in Paquimé were dedicated to raising macaws. Located in a central place in the city, its main entrances are directly linked to the central square. In this small, single story high apartment complex you can still see the niches or drawers in which the animals were raised.

The Mound of the Bird exemplifies the way to build buildings with architectural plants that resemble birds or snakes, as is the case with the Mound of the Serpent, a unique structure in America. The Bird Mound is shaped like a headless bird, and its steps simulate its legs.

The city includes other buildings, such as the southern access complex, the ball court and the house of God, all very austere buildings built with a religious sense, which were the framework to receive the travelers who came from the south.