The danzón has four stages in its history in Mexico: the first, from its arrival to the bitter moments of the revolutionary struggle of 1910-1913.

The second will have a definitive influence on the evolution of radio and is almost concomitant with the first steps of discography, it will have to do with the forms of collective entertainment between the years 1913 and 1933. A third phase will be associated with the reproductive devices and the recreational spaces where the sounds and the ways of interpreting the danzón are reproduced - dance halls with orchestra -, which refers us from 1935 to 1964, when these dance halls were to leave their legitimate space to other dance areas that will transform the models of expression of popular dances and dances. Finally, we can speak of a fourth stage of lethargy and rebirth of old forms that have been reintegrated into popular collective dances -which have never ceased to exist-, to defend their existence and, with it, demonstrate that the danzón has a structure that can make it permanent.

Background to a dance that will never die

Since ancient times, from the presence of the European in what today we know as America, from the 16th century and later, thousands of African blacks arrived on our continent, forced to work especially in three activities: mining, plantations and serfdom. . Our country is no exception to this phenomenon and, from that moment on, a loan process and transculturation processes have been established with the indigenous, European and Eastern population.

Among other aspects, the social structure of New Spain must be taken into account, which, broadly speaking, was made up of a leading Spanish leadership, then the Creoles and a series of subjects not defined by their national origin-Spanish speakers appear. The indigenous caciques will continue immediately, then the exploited natives in struggle for survival, as well as the blacks fighting for work positions. At the end of this complex structure we have the castes.

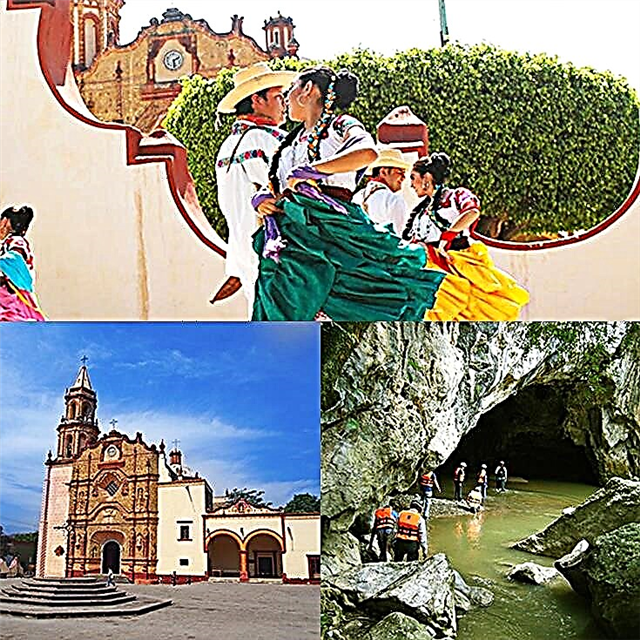

Imagine in this context some of the collective festivities in which all social strata properly participated, such as the Paseo del Pendón, in which the capitulation of the Aztecs of Mexico-Tenochtitlan was commemorated.

At the front of the parade came the royal and ecclesiastical authorities followed by a column in which the participants would appear according to their social position, at the beginning or at the end of the row. In these festivities, after the procession, there were two events that exhibited all the positions of the social scale, such as the bullfights. At another elitist commemorative sarao, the gala of the group in power attended exclusively.

It can be observed that during the years of the colonial period a drastic delimitation was established between "the nobility" and the other human groups, to whom all defects and calamities were alleged. For this reason, the syrups, little dances of the earth and the dances that black people once performed were rejected as immoral, contrary to the laws of God. Thus, we have two separate dance expressions according to the social class that they adopted. On the one hand, the minuettes, boleros, polkas and contradanzas that were taught even in dance academies perfectly regulated by Viceroy Bucareli and that were later banned by Marquina. On the other hand, the people delighted with the déligo, the zampalo, the guineo, the zarabullí, the pataletilla, the mariona, the avilipiuti, the folia and above all, when it came to dancing agitatedly, the zarabanda, the jacarandina and, certainly, the bustle.

The National Independence movement legalized the equality and freedom of human groups; However, moral and religious guidelines still remained in force and could hardly be transgressed.

The stories that that great writer and patrician, Don Guillermo Prieto, have left us of the time, make us reflect on the minimal differences that have occurred in our culture, despite the innumerable technological changes that have occurred in almost 150 years.

The social structure was subtly modified and, although the church lost spaces of economic power during the Reform process, it never ceased to maintain its moral hegemony, which even achieved some strengthening.

The sequence of each and every one of the processes that have been outlined here by leaps and bounds, will be vitally important to understand the current ways of Mexicans to interpret ballroom dances. The same genera, in other latitudes, have different expressions. Here the recurrence of Mexican social pressure will determine the changes of men and women by expressing their taste for dance.

This could be the key to why Mexicans are "stoic" when we dance.

The danzón appears without making much noise

If we say that during the Porfiriato -1876 to 1911- things did not change in Mexico, we would be exposing a big lie, since the technological, cultural and societal changes were evident at this stage. It is probable that the technological transformations have been shown with greater momentum and that they have gradually affected customs and traditions and more subtly in society. To test our appreciation we will take music and its performances in particular. We refer to the dance of San Agustín de Ias Cuevas today Tlalpan, as an example of some other performed back in the nine hundred at the Country Club or the Tivoli deI Elíseo. The orchestral group of these parties was surely made up of strings and wood, mainly, and in closed spaces -cafes and restaurants- the presence of the piano was unavoidable.

The piano was the dividing instrument of music par excellence. At that time the railroad was branching out all over the country, the automobile gave its first filming, the magic of photography began and the cinema showed its first babbling; the beauty came from Europe, especially from France. Hence, in dance Frenchified terms such as "glise", "premier", "cuadrille" and others are still used, to connote elegance and knowledge. Well-to-do people always had a piano in their residence to show off in gatherings with the interpretation of pieces of opera, operetta, zarzueIa, or Mexican operatic songs like Estrellita, or in secret, because it was sinful music, like Perjura. The first danzones arrived in Mexico, which were interpreted on the piano with softness and melancholy, were integrated into this court.

But let's not anticipate vespers and reflect a little on the “birth” of the danzón. In the process of learning about the danzón, Cuban dance and contradanza should not be lost sight of. From these genres the structure of the danzón arises, only a part of them being modified -especially-.

Furthermore, we know that the habanera is an immediate antecedent of great importance, since various master genres arise from it (and what is more important, three “national genres”: danzón, song and tango). Historians place the habanera as a musical form from the mid-19th century.

It is argued that the first contradanzas were transported from Haiti to Cuba and are a graft of Country dance, an English country dance that acquired its characteristic air until it became the global Havana dance; They consisted of four parts until they were reduced to two, dancing in figures by groups. Although Manuel Saumell Robledo is considered the father of the Cuban quadrille, Ignacio Cervantes was the one who left a deep mark in Mexico in this regard. After an exile in the United States he returned to Cuba and, later to Mexico, around 1900, where he produced a good number of dances that influenced the way of Mexican composers such as Felipe Villanueva, Ernesto Elourdy, Arcadio Zúñiga and Alfredo Carrasco.

In many of Villanueva's piano pieces, his dependence on Cuban models is obvious. They coincide for the musical content of the two parts. Often the first has the character of a mere introduction. The second part, on the other hand, is more contemplative, languid, with a rubato tempo and “tropical”, and gives rise to the most original rhythmic combinations. In this aspect, as well as in the greater modulatory fluency, Villanueva surpasses Saumell, as is natural in a composer of the next generation and has more spiritual contacts with the continuator of the Cuban genre, Ignacio Cervantes.

The contradanza was taking an important place in the Mexican tastes of music and dances, but like all dances, it has its forms that for society must be interpreted in accordance with morals and good customs. In all the Porfirian gatherings, the wealthy class maintained the same archaic forms of 1858.

In this way, we have two elements that will make up the first stage of the danzón's presence in Mexico, which runs from 1880 to 1913, approximately. On the one hand, the piano score that will be the vehicle of mass transmission and, on the other, the social norms that will prevent its open proliferation, reducing it to places where morals and good customs can be relaxed.

Times of boom and development

After the thirties, Mexico will experience a true boom in tropical music, the names of Tomás Ponce Reyes, Babuco, Juan de Dios Concha, Dimas and Prieto becoming legendary in the danzón genre.

Then comes the special shout introductory to any interpretation of danzón: Hey family! Danzón dedicated to Antonio and friends who accompany him! expression brought to the capital from Veracruz by Babuco.

Amador Pérez, Dimas, produces the danzón Nereidas, which breaks all limits of popularity, since it is used as a name for ice cream parlors, butchers, cafes, lunches, etc. It will be the Mexican danzón that faces the Cuban Almendra, from Valdés.

In Cuba, the danzón was transformed into cha-cha-chá for commercial reasons, it expanded immediately and displaced the danzón of the dancers' taste.

In the 1940s, Mexico experienced an explosion of hubbub and its nightlife was brilliant. But one fine day, in 1957, a character appeared on the scene brought from those years in which laws were passed to care for good consciences, who decreed:

"The establishments must be closed at one in the morning to guarantee that the worker's family receives their salary and that the family patrimony is not wasted in vice centers," Mr. Ernesto P. Uruchurtu. Regent of the City of Mexico. Year 1957.

Lethargy and rebirth

“Thanks” to the measures of the Iron Regent, most of the dance halls disappeared and, of the two dozen that there were, only three remained: EI Colonia, Los Angeles and EI California. They were attended by the faithful followers of the dance genres, who have maintained through thick and thin the good ways of dancing. In our days, the SaIón Riviera has been added, which in the past was only a room for parties and dancers, a home defender of the fine dances of SaIón, among which the danzón is king.

Therefore, we echo the words of Amador Pérez and Dimas, when he mentioned that "modern rhythms will come, but the danzón will never die."