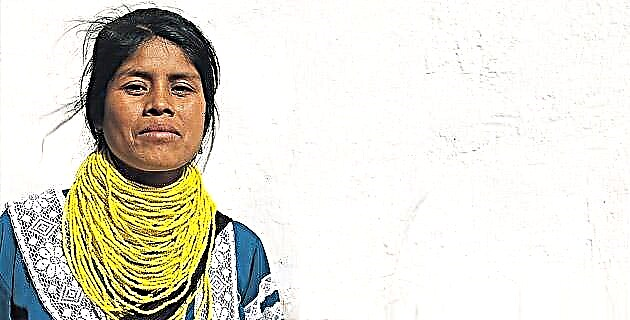

In the extensive territory of the mountains and ravines of the Sierra Madre Occidental, diverse indigenous cultures have inhabited for centuries; some have disappeared and others have reworked the historical processes that have kept them alive to this day.

The limits of the states of Nayarit, Jalisco, Zacatecas and Durango form an inter-technical region where Huichols, Coras, Tepehuanos and Mexicaneros coexist. The first three are majority groups and have served as the subject of historical and anthropological studies, unlike Mexicaneros who have historically remained anonymous.

There are currently three Mexican settlements: Santa Cruz, in the state of Nayarit, and San Agustín de San Buenaventura and San Pedro Jícoras, in the southeast of the state of Durango. The communities are settled in ravines where no roads pass. The displacement is the result of long walks that allow you to enjoy the heat and see villages, rivers and wells. They also offer the opportunity to observe the flora and fauna with rare and beautiful species such as magpies, herons, suckers, squirrels and deer.

In times of drought it is possible to discover the golden and copper tones of the hills, which allow us to imagine human contours and silhouettes.

His story

The Mexicaneros are a group that speaks a variant of Nahuatl. Its origin has generated various controversies, it is unknown if they are of Tlaxcala origin, if it comes from the Sierra that was Nahuatlized during the Colony, or if it is a population that retreated to the Sierra during the same period. The truth is that it is a group that culturally belongs to the archers and their mythology is Mesoamerican. As for the myths, it is said that in ancient times a pilgrimage left the north that went to the center following an eagle. From this pilgrimage, some families stayed in Tenochtitlan and others continued through Janitzio and Guadalajara until they reached their current settlement.

Agricultural ceremonies

The Mexicaneros practice rainfed agriculture on stony soils, so they let a piece of land rest for ten years to use it again. They mainly grow corn and combine it with squash and beans. The work is done by domestic and extended family. Agricultural ceremonies are essential in the social reproduction of the group. The so-called mitotes, an oxuravet custom, are ceremonies of request for rain, appreciation of harvests, blessing of fruits and request for health. In short, it is a life petition ceremony that takes place in courtyards assigned since time immemorial to families with patrilineal surnames and in a communal space located in the political-religious center. They perform between one and five ceremonies for each of the five periods of the year. The communal mitotes are: elxuravetde the oiwit feather (February-March), the aguaat (May-June) and the eloteselot (September-October).

Custom requires a series of abstinences to remain in the yard and participate in activities. The ceremony lasts five days and is directed by a “patio mayor”, trained for five years to hold this lifetime position. The villagers carry flowers and a log, in the morning, until the fourth day. These offerings are deposited on the altar that is directed towards the east. The patio mayor prays or "gives part" in the morning, at noon and in the afternoon; that is, when the sun rises, when it is at the zenith and when it sets.

On the fourth day, at night, the dance begins with the participation of men, women and children. The elder has placed the musical instrument to one side of the fire so that the musician can see the east while he plays it. Men and women dance five sounds around the fire throughout the night and intersperse the “Dance of the Deer”. The sones require an extraordinary performance by the musician, who uses an instrument made up of a large bule, which functions as a resonance box, and a wooden bow with an ixtle string. The bow is placed on the gourd and struck with small sticks. The sounds are Yellow Bird, Feather, Tamale, Deer and Big Star.

The dance concludes at dawn, with the fall of the deer. This dance is represented by a man who carries a deerskin on his back and his head in his hands. They simulate their hunting while being followed by another person who looks like a dog. The deer makes erotic jokes and mischief to the participants. During the night, the majority is in charge of directing the preparation of the ritual food, assisted by the mayordomas and other women of the community.

The "chuina" is the ritual food. It is venison mixed with dough. At dawn, the oldest and most of them wash their faces and stomachs with water. The ceremony includes the words of a ritual specialist who recalls the duty to continue with the abstinences for four more days to "fulfill" the divinities that make their existence possible.

During this ceremony, the verbal and ritual expressions project the group's worldview in a nuanced way; symbols and meanings, in addition to showing the close relationship between man and nature. The hills, the water, the sun, the fire, the big star, Jesus Christ, and the action of man, make it possible to ensure human existence.

Parties

The patronal civic festivals are abundant. Mexicaneros celebrate Candelaria, Carnival, Holy Week, San Pedro, Santiago and Santur.

Most of these festivities are organized by mayordomías whose charge is annual.

The festivities last eight days and their preparation one year. The day before, the eve, the day, the delivery of the dance, among others, are days when the mayordomos offer food to the saints, fix the church and organize with the community authorities to perform the dance of “Palma and Cloth ”, in which young people and a“ Malinche ”participate. Their clothing is colorful and they wear crowns made of Chinese paper.

The dance is accompanied by music, dance movements and evolutions. It is also performed during processions, while the mayordomos carry holy censers.

Holy Week is an extremely rigid celebration for abstinences, such as eating meat, touching the water of the river because it symbolizes the blood of Christ, and listening to music; these reach their maximum degree when it is time to break them.

On the "Saturday of glory" the assistants gather in the church, and a group of violin strings, guitars and guitarrón interpret five polkas. Then the procession with the images leaves, firing rockets, and the mayordomos carry large baskets with the clothes of the saints.

They go to the river, where a steward burns a rocket to symbolize that it is allowed to touch the water. The mayordomos wash the clothes of the saints and put them to dry in the nearby bushes. Meanwhile, the mayordomos offer the attendees, on the other side of the river, a few glasses of "guachicol" or mezcal produced in the region. The images are returned to the temple and the clean clothes are put away again.

Another festival is that of Santur or Difuntos. The preparation of the offering is family and they place offerings in the houses and in the pantheon. They cut zucchini, corn on the cob and peas, and make small tortillas, candles, cook the pumpkins and go to the cemetery cutting the javielsa flower on the way. In the tombs the offerings of adults and those of children are distinguished for coins and sweets or animal cookies. In the distance, over the hills, a movement of lights can be seen in the darkness; They are the relatives who go to the town and the pantheon. After placing their offerings, they go to the church and inside they put other offerings with candles around; then the population watches all night.

People from other communities come to the feast of San Pedro, because they are a very miraculous patron. San Pedro marks the start of the rainy season, and people look forward to that day. On June 29 they offer beef broth at noon; the musicians walk behind whoever hired them and walk through the town. The butlers' kitchen remains awash with women and relatives. At night there is a procession, with dance, authorities, butlers and the entire population. At the end of the procession, they burn countless rockets that illuminate the sky with their fleeting lights for several minutes. For Mexicaneros, each celebration date marks a space in agricultural and festive time.