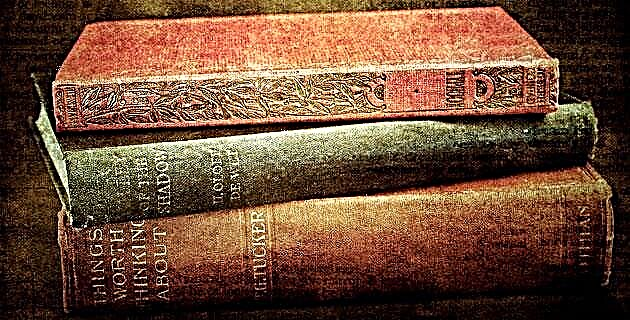

To inquire about the printed culture in the colony is to ask how Western civilization was penetrating our country.

The printed book is not something that exhausts its function in an exclusively practical and subordinate use. The book is a special object to the extent that it is the seat of writing, which allows thought to be reproduced in absence, through time and space. In Europe itself, the invention of the movable type printing press had made it possible to expand to the maximum the possibilities of dissemination of what was thought, through written media, and had given Western culture one of its most powerful devices. With this invention, applied in Gutenberg's Bible between 1449 and 1556, the production of the printed book reached maturity just in time to accompany European expansion, helping it to revive and reproduce Old World cultural traditions in regions and circumstances as remote as those that the Spanish found in American lands.

Slow penetration to the north

The opening of a route through the interior of New Spain is an illustrative case. The Camino de la Plata joined the territories of New Spain with the northern regions, almost always marked out from one realm of mines to another, in the middle of vast sparsely populated regions, under the constant threat of hostile groups, much more rugged and reluctant to the Spanish presence than its southern counterparts. The conquerors also carried their language, their aesthetic criteria, their ways of conceiving the supernatural embodied in a religion, and in general an imagination shaped radically different from that of the indigenous population they encountered. In a process little studied, and less understood, some documentary traces help us to corroborate that the printed book accompanied the Europeans in their slow penetration of the north. And like all the spiritual and material elements that came with them, it came to these regions by the Royal Road from Tierra Adentro.

It must be said that the books did not have to wait for the layout of the route to make their appearance in the area, but rather they arrived with the first forays, as inevitable companions of the advance of the Spanish. It is known that Nuño de Guzmán, the conqueror of New Galicia, carried with him a volume of the Decades of Tito Livio, probably the Spanish translation published in Zaragoza in 1520. Cases such as that of Francisco Bueno, who died on the road from Chiametla to Compostela in 1574, illustrate how from the most illustrious conqueror to the most diligent of merchants they continued to be linked to their civilization in then remote regions, through the company of letters. Bueno carried among his belongings three books on spirituality: The Art of Serving God, a Christian Doctrine and the Vita Expide of Fray Luis de Granada.

Everything seems to indicate that for a long time, the reading and possession of the book in this area was mainly a practice of individuals of European origin or descent. By the second half of the 16th century, indigenous groups north of the central regions continued to have only marginal contact with this foreign object, although they were attracted to its images.

This is suggested by an inquisitorial document from 1561, which is also a sign of a large circulation of books at a relatively early date. Having received the order from Guadalajara to visit the Real de Minas de Zacatecas, in order to locate prohibited works, the vicar Bachiller Rivas found among "the Spaniards and other people of these mines" a sufficient volume of forbidden books to fill three pouches of them, which reveals that the printed matter was not in short supply. Being stored in the sacristy of the church to take them to Guadalajara, the sacristan Antón -of Purépecha origin- in the company of his brother and another Indian friend of his, opened these packages and began to circulate their contents among other Indians. The reference is misleading because it can make us accept an indigenous interest in books without further ado. But Anton and the other Indians who were questioned confessed that they could not read, and the sacristan declared that he had taken the books to look at the figures they contained.

The craving for reading materials that is guessed in some cases was satisfied by various mechanisms. Most of the time, the books were transported as personal effects, that is, the owner brought them with him from other regions as part of his luggage. But on other occasions they were moved as part of a commercial traffic that originated in Veracruz, where each shipment of books was carefully inspected by the officials of the Inquisition, especially from 1571, when the Holy Office was established in the Indies. to prevent the contagion of Protestant ideas. Later - almost always after stopping in Mexico City - the printed matter found their way through the intermediation of a book dealer. The latter would send them to the interested party, consigning them to a mule driver who carried the books north on the back of a mule, in sheltered wooden boxes covered with leather to prevent inclement weather and hazards on the road from damaging such delicate cargo. All the existing books in the north reached the northern regions in some of these ways, and their existence in the areas covered by the road can be documented from the second half of the 16th century in Zacatecas, and from the 17th century in places like Durango. , Parral and New Mexico. Used and sometimes new, the books covered a long way from their departure from the European printing shops, or at least from those established in Mexico City. This situation lasted until the third decade of the 19th century, when some traveling printers arrived in these parts during or after the independence struggle.

The commercial aspect

Documenting the commercial aspect of the circulation of the books is, however, an impossible undertaking due to the fact that the books did not pay the alcabala tax, so that their traffic did not generate official records. Most of the permits to transport books to the mining regions that appear in the archives correspond to the second half of the 18th century, when vigilance on the circulation of printed matter was intensified to prevent the diffusion of the ideas of the Enlightenment. In fact, the testimonies that are related to the transmission of deceased property - testimonies - and the ideological control that was established by monitoring the circulation of printed matter, are the operations that most frequently let us know what type of texts circulated on the Camino de La Plata to the regions it connects.

In numerical terms, the largest collections that existed in colonial times were those gathered in the Franciscan and Jesuit convents. The Zacatecas College of Propaganda Fide, for example, housed more than 10,000 volumes. For its part, the library of the Jesuits of Chihuahua, being inventoried in 1769, had more than 370 titles -which in some cases covered several volumes-, not counting those that were separated because they were prohibited works or because they were already very deteriorated. . The Celaya library had 986 works, while that of San Luis de la Paz reached a number of 515 works. In what remained of the library of the Jesuit College of Parras, in 1793 more than 400 were recognized. These collections abounded in volumes useful for the healing of souls and the religious ministry exercised by the friars. Thus, missals, breviaries, antiphonaries, bibles and sermon repertoires were required contents in these libraries. The printed matter was also useful auxiliary in fostering devotions among the laity in the form of novenas and lives of saints. In this sense, the book was an irreplaceable auxiliary and a very useful guide to follow the collective and individual practices of the Christian religion (mass, prayer) in the isolation of these regions.

But the nature of missionary work also demanded more worldly knowledge. This explains the existence in these libraries of dictionaries and auxiliary grammars in the knowledge of autochthonous languages; of the books on astronomy, medicine, surgery and herbalism that were in the library of the Colegio de Propaganda Fide de Guadalupe; or the copy of the book De Re Metallica by Jorge Agrícola - the most authoritative on mining and metallurgy of the time - which was among the books of the Jesuits of the Convent of Zacatecas. The marks of fire that were made on the edge of the books, and that served to identify their possession and prevent theft, reveal that the books arrived at the monasteries not only by purchase, as part of the endowments that the Crown gave, for For example, to the Franciscan missions, but on occasions, when sent to other monasteries, the friars took volumes from other libraries with them to help with their material and spiritual needs. Inscriptions on the pages of the books also teach us that, having been the individual possession of a friar, many volumes became of the religious community upon the death of their possessors.

Educational tasks

The educational tasks to which the friars, especially the Jesuits, dedicated themselves, explains the nature of many of the titles that appeared in the conventual libraries. A good part of these were volumes on theology, scholarly commentaries on biblical texts, studies and commentaries on Aristotle's philosophy, and rhetoric manuals, that is, the type of knowledge that at that time constituted the great tradition of literate culture and that these educators guarded. The fact that most of these texts were in Latin, 'and the lengthy training required to master scholastic law, theology, and philosophy, made this a tradition so restricted that it easily died out once the institutions disappeared. where it was grown. With the religious orders extinct, a good part of the convent libraries were victims of looting or neglect, so that only a few have survived, and these in a fragmentary way.

Although the most notorious collections were located in the major monasteries, we know that the friars brought significant quantities of books even to the most remote missions. In 1767, when the expulsion of the Society of Jesus was decreed, the existing books in nine missions in the Sierra Tarahumara totaled a total of 1,106 volumes. The mission of San Borja, which was the one with many volumes, had 71 books, and that of Temotzachic, the most assorted, with 222.

The laity

If the use of books was naturally more familiar to religious, the use that lay people gave to the printed book is much more revealing, because their interpretation of what they read was a less controlled result than that achieved by those who had been undergoing school training. The possession of books by this population is almost always traced thanks to testamentary documents, which also show another mechanism of the circulation of books. If any deceased had possessed books while they were alive, they were carefully valued for auction with the rest of their property. In this way the books changed owners, and on some occasions they continued their route further and further north.

The lists that are attached to wills are not usually very extensive. Sometimes there are only two or three volumes, although on other occasions the number goes up to twenty, especially in the case of those whose economic activity is based on a literate knowledge. An exceptional case is that of Diego de Peñalosa, governor of Santa Fe de Nuevo México between 1661-1664. He had about 51 books in 1669, when his properties were confiscated. The most extensive lists are found precisely among the royal officials, the doctors and the legal experts. But outside of the texts that supported a professional task, the books that are freely chosen are the most interesting variable. Neither should a small list be misleading, because, as we have seen, the few volumes at hand took on a more intense effect as they were the object of repeated readings, and this effect was extended through the loan and the assiduous comment that used to arouse around them. .

Although reading provided entertainment, it should not be thought that distraction was the only consequence of this practice. Thus, in the case of Nuño de Guzmán, it should be remembered that the Decades of Tito Livio is an exalted and magnificent story, from which Renaissance Europe got an idea not only of how military and political power had been built of Ancient Rome, but of the greatness of it. Livy, rescued to the West by Petrarch, was one of Machiavelli's favorite readings, inspiring his reflections on the nature of political power. It is not remote that his narration of epic journeys, like that of Hannibal through the Alps, was the same as a source of inspiration for a conqueror in the Indies. We can remember here that the name of California and the explorations to the north in search of El Dorado were also motifs derived from a book: the second part of the Amadís de Gaula, written by García Rodríguez de Montalvo. More space would be needed to describe the nuances and to review the various behaviors that this passenger, the book, gave rise to. These lines only aspire to introduce the reader to the real and imaginary world that the book and the reading generated in the so-called northern New Spain.