The history of the Mexica past has gradually been unraveling; The Sigüenza Codex is one of the most valuable means by which we have known some aspects of the life of this ancestral town.

The codices, documents of pre-Hispanic tradition made by a tlacuilo or scribe, could be religious, for the use of the priests of different cults, they had also been dedicated to economic matters used as civil or property registration and others that consigned the important historical events. When the Spanish arrived and imposed a new culture, the making of religious codices practically disappeared; However, we do find a large number of documents with pictograms that refer to specific territories, where they delimit properties or register different matters.

The Sigüenza Codex

This codex is a special case, its theme is historical and deals with the origins of the Aztecs, their pilgrimage and the founding of the new city of Tenochtitlan. Although it was made after the Conquest, it still presents some distinctive features of indigenous cultures. It can be affirmed that an issue like the Aztec migration was very important for that people, who arrived in the Valley of Mexico lacking a glorious past.

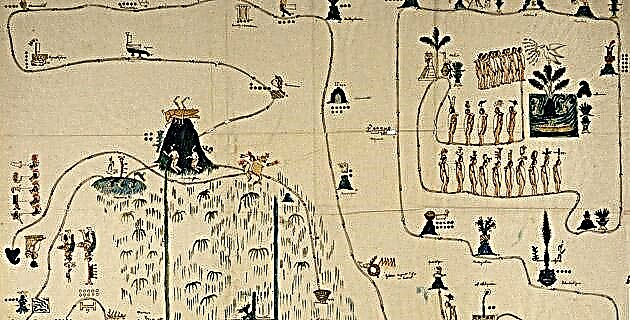

Throughout the document two different worlds come together and amalgamate. The Renaissance human proportion, the use of wash ink without delimitation of the contour, the volume, the freer and more realistic drawing, the shading and the use of glosses in the Latin alphabet, determine the European influence that has already become intrinsic in the indigenous discourse. that, given the time the codex is made, is difficult to dissociate. However, the traditions rooted for centuries in the soul of the tlacuilo persist with great force and thus we observe that toponymic or place glyphs are still represented with the hill as a locative symbol; the path is indicated with footprints; the thickness of the contour line persists with determination; the orientation of the map is preserved with the East in the upper section, unlike the European tradition in which the North is used as the reference point; small circles and the representation of the xiuhmolpilli or bundle of rods are used to mark time lapses; There is no horizon, nor is there an attempt to make portraits and the order of reading is given by the line that marks the pilgrimage route.

As its name indicates, the Sigüenza Codex belonged to the famous poet and scholar Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (1645-1700). This invaluable document is in the National Library of Anthropology and History of Mexico City. Although the Spanish conquest wanted to cut off any connection with the past, this codex is authentic proof of the indigenous concern, the look towards the past and the cultural roots of the Mexica, which, although weakened, is evident throughout the century XVI.

The pilgrimage begins

As the well-known legend says, the Aztecs leave their homeland Aztlán under the aegis of their god Huitzilopochtli (the southern hummingbird). During the long pilgrimage they visit different places and the tlacuilo or scribe will take us by the hand through the windings of the route. It is a narration of experiences, victories and calamities, the syncretism between the magical mythical and the historical is intertwined through the management of the past for a political purpose. Aztec power spread from the founding of Tenochtitlan, and the Mexica remade their legends to appear as a people of honorable ancestors, they say they are descendants of the Toltecs and share their roots with the Colhuas, hence the always mentioned Colhuacan. In fact, the first site they visit is Teoculhuacan, alluding to the mythical Culhuacan or Colhuacan, represented with the crooked hill in the right corner of the four aquifer; Inside the latter we can see the islet that represents Aztlán, where a majestic bird stands tall before his followers, urging them to begin a long journey to a better land.

The men organize themselves, either by tribes or following a certain chief. Each character wears their emblem attached to their head with a thin line. The author of the codex lists 15 tribes that undertake the journey, each one represented by its chief, separates five characters that leave first led by Xomimitl, who begins the pilgrimage bearing the symbol of his name, ‘arrowed foot’; It is followed by what is probably called Huitziton, later Xiuhneltzin, mentioned in the 1567 codex, deriving its name from xiuh-turquoise, Xicotin and the last Huitzilihuitl, head of the Huitznaha recognized by the hummingbird head.

These five characters arrive in Aztacoalco (aztlatl-garza, atl-agua, comitl-olla), site where the first confrontation takes place since leaving Aztlán, -according to this document- and we observe the pyramid with the burned temple, symbol of defeat that happened in this place. Here 10 more characters or tribes come together who march along the same road to Tenochtitlan, the first one who heads this new group has not been identified and there are several versions, it is likely that he is the chief of the Tlacochalcas (which means where they are the darts are stored), Amimitl (the one who carries the Mixcoatl rod) or Mimitzin (name that comes from mimitl-arrow), the next, which incidentally will play an important role later is Tenoch (that of the stone prickly pear), then the head of the matlatzincas appears (who come from the place of the nets), they are followed by Cuautlix (the face of an eagle), Ocelopan (the one with the tiger's banner), Cuapan or Quetzalpantl goes behind, then Apanecatl (water channels) walk, Ahuexotl (water willow), Acacitli (reed hare), and the latter which has probably not been identified to date.

Huitzilopochtli's wrath

After passing through Oztocolco (oztoc-grotto, comitl-olla), Cincotlan (near the pot of ears), and Icpactepec, the Aztecs arrive at a site where they erect a temple. Huitzilopochtli, seeing that his followers had not waited until they reached the sacred place, becomes enraged and with his divine powers he sends a punishment on them: the tops of the trees threaten to fall when a strong wind blows, the rays that fall from the sky collide against the branches and the rain of fire sets fire to the temple, located on the pyramid. Xiuhneltzin, one of the chiefs, dies on this site and his shrouded body appears in the codex to record this fact. In this place the Xiuhmolpillia is celebrated, a symbol that appears here as a bundle of rods on a tripod pedestal, it is the end of a 52-year cycle, it is when the natives wonder if the sun will rise again, if there will be life the next day.

The pilgrimage continues, they pass through different places, the time accompanied by periods of stay that vary from 2 to 15 years in each place, it is indicated by small circles on one side or below each place name. Always following the footprints that mark the path, guided by their warrior god, they continue the march towards an unknown place, passing through many towns such as Tizaatepec, Tetepanco (on the stone walls), Teotzapotlan (place of the stone sapotes), and so on, until reaching Tzompanco (where the skulls are strung), an important site repeated in almost all the chronicles of the pilgrimage. After going through several more towns, they arrive at Matlatzinco where there is a detour; the Anales de Tlatelolco narrate that Huitzilihuitl lost his way for a time and then rejoined his people. The divine force and the hope of a promised place generates the necessary energy to continue along the way, they visit several important sites such as Azcapotzalco (anthill), Chalco (place of the precious stone), Pantitlan, (site of flags) Tolpetlac (where they are los tules) and Ecatepec (hill of Ehécatl, god of the wind), all of them also mentioned in the Strip of the Pilgrimage.

The battle of Chapultepec

Likewise, they visit other lesser known sites until after a certain time they settle in Chapultepec (chapulín hill) where the character Ahuexotl (water willow) and Apanecatl (that of Apan, -water channels-) lie dead at the foot of the mountain after a confrontation against the Colhuas, a group that had previously settled in these places. Such was the defeat that some flee to what would later become Tlatelolco, but on the way they are intercepted and Mazatzin, one of the Mexican leaders, is dismembered; other prisoners are taken to Culhuacan where they die decapitated and some more hide in the lagoon between the tulares and the reed beds. Acacitli (cane hare), Cuapan (the one with the flag) and another character poke their heads out of the undergrowth, are discovered and taken prisoner in front of Coxcox (pheasant), chief of the Colhua, who seated on his icpalli or throne receives the tribute from his new servants, the Aztecs.

From the battle in Chapultepec, the lives of the Mexica changed, they became serfs and their nomadic stage practically ended. The tlacuilo captures the latest data from the pilgrimage in a small space, bringing together the elements, zigzagging the path and sharpening the curvatures of the route. The most interesting thing is that at this point you have to turn the document practically upside down to be able to continue reading, all the glyphs that appear after Chapultepec are in the opposite direction, the marshy and lake terrain that characterizes the Valley of central Mexico is observed by the appearance of wild herbs that surround these last locatives. This is the only space where the author grants himself the freedom to paint the landscape.

Later, the Aztecs manage to establish themselves in Acolco (in the middle of the water), and after passing through Contintlan (next to the pots), they fight again at a site near Azcatitlan-Mexicaltzinco with some other unidentified people here. Death, symbolized by a beheaded, once again harasses the people on pilgrimage.

They walk bordering the lakes of the Valley of Mexico passing through Tlachco, where the ball court is located (the only place drawn in an aerial plan), Iztacalco, where there is a fight indicated by the shield on the right side of the house. After this event, a woman of the nobility, who was pregnant, has a child, so this place is named Mixiuhcan (place of childbirth). After giving birth, it was customary for the mother to take the sacred bath, temacalli from which the name of Temazcaltitlan is derived, a place where the Mexicans settle for 4 years and celebrate the Xiuhmolpillia (celebration of the new fire).

The foundation

Finally, Huitzilopochtli's promise is fulfilled, they arrive at the site indicated by their god, settle in the middle of the lagoon and found the city of Tenochtitlan here represented by a circle and a cactus, a symbol that marks the center and the division of the four neighborhoods. : Teopan, today San Pablo; Atzacoalco, San Sebastián; Cuepopan, Santa María and Morotlan, San Juan.

Five characters appear as founders of Tenochtitlan, among them the renowned Tenoch (the one with the stone prickly pear) and Ocelopan (the one with the tiger banner). It is worth mentioning that two water channels are built that come from Chapultepec to supply the city with the spring that arises from this place, and that is indicated in this codex with two parallel blue lines, which run through the swampy terrain, until reaching the city. The past of the Mexican indigenous peoples is recorded in pictographic documents that, like this one, transmit information about their history. The study and dissemination of these important documentary testimonies will allow all Mexicans to fully understand our origins.

Batia Fux