The ethnic diversity of the Oaxacan territories gave evangelization a different character than it had in other parts of New Spain; although in general the same policy was followed regarding the way of incorporating indigenous people into Western culture.

The ethnic diversity of the Oaxacan territories gave evangelization a different character than it had in other parts of New Spain; although in general the same policy was followed regarding the way of incorporating indigenous people into Western culture.

Agroso modo, it can be said that in Oaxaca the mendicant church played a much more important and decisive role than the secular clergy. Proof of this are the monumental convents that are still standing; That is why the Dominicans, rightly so, are considered "the forgers of the Oaxacan civilization." However, the dominance that they came to have over the indigenous people emerged, on several occasions, in violent acts.

The convents of the Mixteca Alta are reputed for many reasons: Tamazulapan, Coixtlahuaca, Tejupan, Teposcolula, Yanhuitlán, Nochixtlán, Achiutla and Tlaxiaco, among the most important; in the central valleys, without a doubt, the most spectacular building is the convent of Santo Domingo de Oaxaca (Mother House of the Province and College of Major Studies), but we must not forget the houses of Etla, Huitzo, Cuilapan, Tlacochahuaya, Teitipac and Jalapa de Marqués (nowadays disappeared), among other things; almost all on the route to Tehuantepec. In each one of these buildings the same architectural party can be seen, "invented" by the mendicants during the 16th century: atrium, church, cloister and orchard. In them, the fashions and artistic tastes that the Spaniards brought were reflected, along with various plastic reminiscences, especially sculptural, of pre-Hispanic lineage.

In addition to such complete plastic integration, the monumental proportions of these factories stand out: wide atria precede the convents, being that of Teposcolula one of the largest.

The open chapels can be "niche type" -as in Coixtlahuaca- or with several naves as in Teposcolula and Cuilapan. Of the churches, that of Yanhuitlán, for many reasons, is one of the most significant. Unfortunately almost all of the Oaxacan territory is a seismic zone; For this reason, telluric movements have repeatedly destroyed the old cloisters. However, its old disposition can still be seen, as in Etla or Huitzo. The convent gardens constituted, for centuries, the pride of the Dominican religious, who made the plants of the land grow, next to trees and vegetables from Castile.

However, it is inside the churches where you can still admire the richness of the trousseau with which they were adorned: mural painting, altarpieces, tables and oil paintings, sculptures and organs, furniture, liturgical goldsmiths and religious clothing show the wealth and generosity of those who paid for it (individuals and indigenous communities).

The convents were foci from which Western civilization radiated: together with the teaching of the Catholic religion, a new technology was unveiled to better and more easily exploit the earth.

Plants that came from far away (wheat, sugar cane, coffee, fruit trees) modified the varied Oaxacan landscape; change that accentuated the fauna -major and minor- coming from beyond the sea (cattle, goats, horses, pigs, birds and domestic animals). And the introduction of the cultivation of the silkworm should not be lost sight of, which together with the exploitation of the scarlet constituted the sustenance, for more than three centuries, of the economy of various regions of Oaxaca.

In the convents too, making use of more unusual didactic resources (for example, music, art and dance), the friars taught the natives the rudiments of a spiritual culture of a very different sign from the one they had before the arrival of the conquerors; at the same time, learning the mechanical arts was shaping the image of the indigenous Oaxacan.

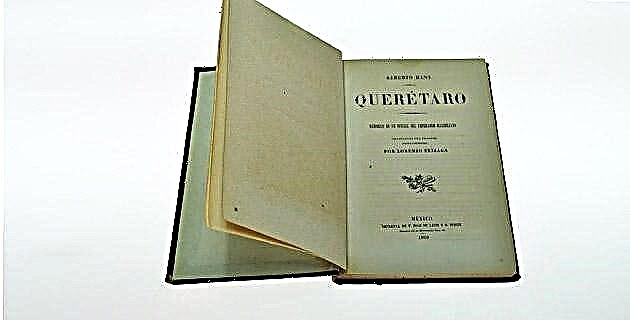

But it would be unfair not to point out that the friars also learned countless indigenous languages, in addition to Zapotec and Mixtec; Dictionaries, doctrines, grammars, devotionals, sermons, and other arts in vernacular languages, written by Dominican friars, abound. The names of Fray Gonzalo Lucero, Fray Jordán de Santa Catalina, Fray Juan de Córdoba and Fray Bernardino de Minaya, are among the most illustrious of the community of preachers established in Oaxaca.

Now, the secular clergy also made an appearance in Oaxacan lands from an early date; although once the bishopric of Antequera was erected, its second holder for twenty years (1559-1579) was a Dominican: Fray Bernardo de Alburquerque. As time passed, the Crown was particularly determined that the bishops were secular. In the 17th century, illustrious clergymen such as Don Isidoro Sariñana and Cuenca (Mexico, 1631-Oaxaca, 1696), canon of the Cathedral of Mexico, who arrived in Oaxaca in 1683, ruled the miter.

If the convents represent the presence of the mendicant clergy in the different regions of the entity, in certain churches and chapels -whose architectural part is certainly different- the trace of the secular clergy is perceived. Since the city of Antequera was drawn up by the builder Alonso García Bravo, the Cathedral of Oaxaca occupied one of the main sites around the square; the building that would house the episcopal see was drawn up and built in the 16th century, following the cathedral model of three naves with twin towers.

With the passing of time and due to the earthquakes that damaged them, it was rebuilt at the beginning of the 18th century, becoming the most important religious building in the city, especially from an administrative point of view; Its monumental facade-screen in green quarry is one of the typical examples of the Oaxacan Baroque. Not far from it - and in a way competing with it - stand the Santo Domingo convent and the Nuestra Señora de la Soledad sanctuary. The first of them, together with the Chapel of the Rosary, is a pristine example of the plaster work that earned so much fortune in Puebla and Oaxaca; in that temple art and theology go hand in hand, converted into a perennial hymn to the glory of God and the Dominican order. And in the monumental façade-screen of La Soledad there is also a page of theology and history whose images receive the first prayers of the faithful, before they bow before the suffering lady.

Many other temples and chapels configure the urban image of Oaxaca and its surroundings; some are very modest, for example Santa Marta del Marquesado; others, with its innumerable treasures, testify to the wealth of Antequera: San Felipe Neri, full of golden altarpieces, San Agustín with its almost filigree façade; some more evoke different religious orders: Mercedarians, Jesuits, Carmelites, without forgetting various branches of religious, whose presence is felt in monumental factories such as the old convent of Santa Catarina or the convent of La Soledad. And still, due to its name and proportions, the group of Los Siete Príncipes (currently Casa de la Cultura) dazzles us, as well as the convents of San Francisco, Carmen Alto and the church of Las Nieves.

The artistic influence of these monuments exceeded the scope of the valleys and can be appreciated very well in remote regions such as the Sierra de Ixtlán. The church of Santo Tomás, in the latter town, was surely built and decorated by artisans from Antequera. The same can be said of the Calpulalpan temple where it is not known what to admire more, if its architecture or the altarpieces full of golden images.