The codices are invaluable testimonies for the knowledge of the pre-Hispanic cultures and of the peoples during the colonial era, since they are consigned, among others, historical facts, religious beliefs, scientific advances, calendrical systems and geographical notions.

According to J. Galarza, “the codices are the manuscripts of the Mesoamerican natives who fixed their languages by means of a basic system of the use of the encoded image, derived from their artistic conventions. The characteristic contempt of the conqueror towards the culture that he submits, the lack of culture of several others, historical events and the time that forgives nothing are some causes of the destruction of innumerable pictographic testimonies.

Currently, most of the codices are guarded by various national and foreign institutions, and others, without a doubt, remain protected in different communities located throughout the Mexican territory. Fortunately, a large part of these institutions are dedicated to the preservation of documents. Such is the case of the Autonomous University of Puebla (UAP), which, aware of the poor state of the Yanhuitlán Codex, asked the National Coordination for the Restoration of Cultural Heritage (CNRPC-INAH) for their collaboration. Thus, in April 1993 various studies and investigations were started on the codex, necessary for its restoration.

Yanhuitlán is located in the Mixteca Alta, between Nochistlán and Tepozcolula. The region where this town was located was one of the most prosperous and coveted by the encomenderos. The outstanding activities of the region were the extraction of gold, the rearing of the silkworm and the cultivation of the cochineal. According to sources, the Yanhuitlán Codex belongs to the boom period that this region experienced during the 16th century. Due to its eminently historical character, it could be considered as a section of the annals of the Mixtec region, where the most important events related to the life of the indigenous people and the Spaniards at the beginning of the Colony were noted.

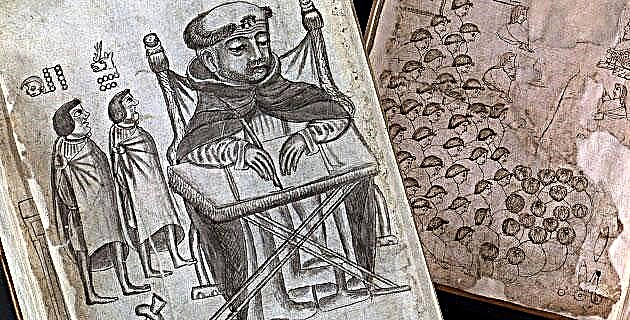

The various sheets of the document present an extraordinary quality of the drawing and the line in a “[…] fine mixed style, Indian and Hispanic”, affirm the authors of the consulted books. If the investigations around the historical and pictographic interpretation of the documents is of utmost importance, the identification of the constituent materials, the study of the manufacturing techniques and a thorough evaluation of the deterioration, are essential to determine the appropriate restoration processes. to each particular case, respecting the original elements.

Upon receiving the Yanhuitlán Codex, we find ourselves in front of a document bound with a leather folder, whose plates, a total of twelve, contain pictographs on both sides. To know how a document was made, the different components of the work and their elaboration technique must be considered separately. As original elements of the codex we have, on the one hand, paper as a receiving unit and, on the other, inks as a vehicle for written expression. These elements and the way they are combined give rise to the manufacturing technique.

The fibers used in the elaboration of the Yanhuitlan codex turned out to be of vegetable origin (cotton and linen), which were commonly used in European paper. Let us not forget that at the beginning of the colony, the time in which this codex was made, there were no mills to make paper in New Spain, and therefore their production was different from the traditional European one. The manufacture of paper and its trade were subject in New Spain to rigid and limited provisions imposed by the Crown throughout 300 years, in order to preserve the monopoly in the metropolis. This was the reason why for several centuries New Spain had to import this material, mainly from Spain.

Paper manufacturers used to popner their product with “watermarks” or “watermarks”, so diverse that they allow to some extent identify the time of its production and, in some cases, the place of origin. The watermark that we find in several plates of the Yanhuitlan Codex is identified as "The Pilgrim", dated by researchers around the middle of the 16th century. Analysis revealed that two kinds of inks were used in this codex: carbon and iron gall. The contour of the figures was made based on lines of different densities. The shaded lines were made with the same ink but more "diluted", in order to give volume effects. It is probable that the lines have been executed with bird feathers -as was done at the time-, of which we have an example in one of the plates of the codex. We assume that the shading was done with a brush.

The organic materials used in the manufacture of documents make them fragile, so they easily deteriorate if they are not in the right medium. Likewise, natural disasters such as floods, fires and earthquakes can seriously alter them, and of course wars, robberies, unnecessary manipulations, etc. are also destructive factors.

In the case of the Yanhuitlan Codex, we do not have enough information to determine its environmental environment over time. However, its own deterioration may shed some light on this point. The quality of the materials that make up the palel greatly influence the degree of destruction of the document, and the stability of the inks depends on the products with which they were made. The mistreatment, the negligence and especially the multiple and inconvenient interventions, were forever reflected in the codex. The main concern of the restorer must be the safeguarding of originality. It is not a matter of beautifying or modifying the object, but simply of keeping it in its state - stopping or eliminating deterioration processes - and effectively consolidating it in an almost imperceptible way.

The missing parts were restored with materials of the same nature as the original, in a discreet but visible way. No damaged item can be removed for aesthetic reasons, as the integrity of the document would be altered. The legibility of the text or drawing should never be altered, so it is essential to choose thin, flexible and extremely transparent materials to reinforce the work. Although the general criteria of minimal intervention should be followed in most cases, the alterations that the codex presented (largely the product of inappropriate interventions) had to be eliminated to stop the damage they caused to it.

Due to its characteristics, degree of deterioration and fragility, it was essential to provide the document with an auxiliary support. This would not only restore its flexibility but would reinforce it without altering the legibility of the writing. The problem we were facing was complex, which required a thorough investigation to choose the right materials and select the preservation techniques according to the conditions of the codex.

A comparative study was also made between materials traditionally used in the restoration of graphic documents, as well as the specific techniques that have been used in other cases. Finally, an evaluation was carried out to choose the ideal materials according to the established criteria. Before joining the auxiliary support to the sheets of the work, cleaning processes were carried out using various solvents to eliminate those elements and substances that altered its stability.

The best support for the document turned out to be silk crepeline, thanks to its characteristics of optimum transparency, good flexibility and permanence in suitable preservation conditions. Among the different adhesives studied, the starch paste was the one that gave us the ideal results, due to its excellent adhesive power, transparency and reversibility. At the end of the conservation and restoration of each one of the plates of the codex, they were bound again following the format that they presented when they reached our hands. Having participated in the recovery of a document of great value, such as the Yanhuitlán Codex, was for us a challenge and a responsibility that filled us with satisfaction knowing that the permanence of another cultural asset, part of our rich historical legacy.