I have a scalpel in my hand; I see very closely a large fragment of pre-Hispanic mural painting from Las Higueras, Veracruz, covered with white conglomerates (they are salts, as they have explained to me extensively).

I keep the razor static a few inches from the pictorial surface. My vision exclusively encompasses the color detail, the slightly yellowish crusts; the metal handle that I hold without moving and the cuff of a still white coat. I go over one by one the detailed instructions on how to proceed to “decarbonize” the paint. She was so enthusiastic that the most important thing was the experience she was living: to intervene directly with an instrument on the cultural heritage of the nation; It seemed to me as if my classmates, the teacher, the assistant were not present.

He was intentionally pondering the action he was about to take. I was frozen for a few moments (then they told me that they were looking at me in silence). I decided to start, I lowered my hand, I scraped without fear but with some uncertainty; I did not want to scratch the paint for any reason. It was the first moment when, as a student of the restoration career, she practiced a process for the conservation and better appreciation of an original work, of a cultural asset. This experience left an imprint on my life and my perception of cultural heritage.

During my years as a student at the Manuel deI Castillo Negrete National Conservation, Restoration and Museography School of the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), day after day I received theoretical and practical teachings that were modifying my way of being and proceeding : they trained me as a restorer by opening up a vast panorama of cultural heritage to me and they made me aware of the importance of its conservation, of the role that the inheritance of the ancestors plays in shaping our identity. I came out of this school prepared to face problems of damages and alterations, both conceptual and material, of the restoration.

The Mexican restorer has the foundations to provide preservation solutions in practically any type of work, technique or material (ceramics, mural painting, easel painting, paper and photographs, metals, stone, wood and polychrome sculpture, archaeological objects, textiles and musical instruments), with the certainty that the theory is the same for each type of creation, even though its application, treatments and procedures are different. On the other hand, the superspecialization of colleagues from other countries is far from us.

The exercise of the profession has not always been easy; And it is not that in Mexico there are few assets to restore; rather it is the reverse. In reality, there are few institutions that include restoration among their objectives. This situation is more acute in the province (which speaks of the great task in this field).

It is worth taking a look at history to remember how the School was founded and what its impact has been in the field of cultural heritage. Men protect, conserve and wish to perpetuate what we value. Goods acquire importance when we recognize them a special meaning, which is closely linked to knowledge. For example, if we know how the works of our ancestors were produced and used, they will have historical value for our culture. In the same way, we will avoid destruction and we will rescue from the damage suffered those goods that we appreciate and therefore know about.

Restoration has evolved linked to art and history. For centuries the motive was the desire to maintain beauty; of the work, its aesthetic appreciation and not its authenticity were transcendent. For the sake of beauty, multiple acts were committed that we would now classify as outrages or even "forgeries".

As a particular feature in my training, I remember the emphasis that the teachers placed, stressing ad nauseam, on respecting the original as an essential attitude of the restorer.

The Italian cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum paralyzed in time by the ashes of the eruption of Vesuvius were discovered in the 18th century. The diversity of works and objects found in the excavations made the rigidity of the aesthetic approaches that governed the restoration shake and left aside the goods not considered "works of art", since it seemed more urgent to study and protect these recently found testimonies for history. .

In our century there is a rise in archeology and the social sciences, and the study and interpretation of archaeological discoveries, of artisanal and industrial works of other times lead to a much broader vision of the remains to be protected. Also driving the advancement of the discipline is the vertiginous technological-scientific progress and the acceptance, by governments, of its mission to transmit tangible evidence of historical knowledge that together with intangible assets and values make up the identity of peoples.

The singular impression left me by a professor's explanation of two objects that had arrived at the ethnographic material workshop remains in my memory: a pre-Hispanic basket that had not disintegrated, coming from an excavation, in which there was a kind of small pieces of paper. folded and inside these, tomato seeds: they were Mesoamerican tacos. The other object was a water bread that had stopped being made some 40 years ago and was now exhibited in the Museum of Handicrafts in Pátzcuaro; the basket, the tacos and the bread had to be preserved for their cultural value.

Mesoamerican production is very far from Hellenistic proportions taken as European canons of beauty. Our country encompasses its rich pre-Hispanic legacy in an extensive anthropological framework and identifies it with the concept of “cultural heritage”.

Since its foundation in 1939, INAH has been the agency par excellence in charge of restoring the nation's cultural heritage. Once established, the restoration in Mexico is institutionalized.

The United Nations Organization for Education, Science and Culture (UNESCO) (created in 1946) made a call for help in favor of threatened monuments in Upper Egypt and Sudan. The excellent response led the Organization to draw up a list with the most relevant creations of man and the most beautiful and intact ecological reserves. Thus, an idea was consolidated until then only understood: there is a collective responsibility of all countries with respect to the monuments that constitute the material expression of civilizations whose importance is such that they belong to the history of the entire humanity.

The current concept of “world heritage” defends both monuments, reserves, cultural complexes and the surrounding nature, as well as the Auchwitz-Birkenau horror sites and the island of Gorée –whose distance from artistic manifestations is abysmal-, which could be instituted as "antimonuments".

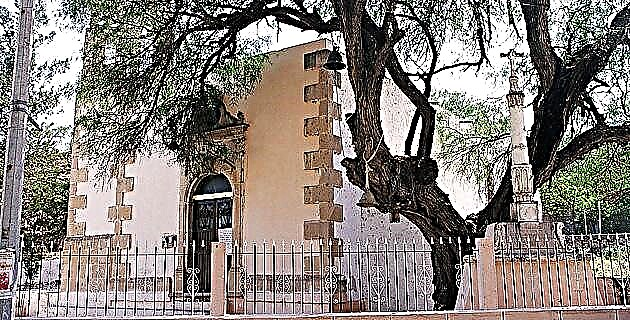

The government of Mexico and UNESCO established an agreement for the creation of the School for the Conservation and Restoration of Artistic Heritage in the ex-convent of Churubusco, Coyoacán. The first intensive courses soon became (1968) formal studies (1968) of five years, and were accepted from 1977 by the Directorate General of Professions (SEP). In that year it was called the "Manuel deI Castillo Negrete" National Conservation, Restoration and Museography School, in memory of its founder.

The School acquired international recognition, as it was a pioneer in the world by offering the Bachelor's Degree in Restoration of Movable Property. Due to its recent establishment, a good part of society is completely unaware of our work.

The master's degree in Architectural Restoration that is taught at the School is the second oldest in the country and the first that has educated nationals and foreigners without interruption. Likewise, it is a precursor in the training of museum designers, and for some time offered a master's degree in Museology.

Despite the enormous need that Mexico has for competent people in the areas it serves, it is the only institution in the country dedicated to superior training of human resources, in order to ensure the specialized protection and dissemination of Mexican cultural heritage. .

Nowadays, applications are received from foreign applicants, but the demand for admission from Mexicans is, unfortunately, well above the capacity of the physical space it has. The facilities were built in the early 1960s on a temporary basis and have not been replaced, improved, or expanded. In the 1980s, the School and the Cultural Heritage Restoration Directorate (now the National Coordination) were administratively separated. For this reason, the shared spaces are subdivided and the areas of the School are substantially reduced.

The funding received by the School has allowed it to continue operating, but not to grow or improve in terms of its spaces, which have deteriorated over time. Mexico is justly proud of its vast and rich cultural heritage, which it also promotes with the remunerative tourism company; However, the School where it trains professionals for its specialized restoration, research and dissemination has serious shortcomings.

It is honest to mention that, despite all of the above, the academic and administrative team has not failed to fulfill the commendable work of teaching. However, it is necessary to sustain and increase the quality of teaching and open new options for specialization and updating of teachers and graduates. The National School of Conservation, Restoration and Museography fulfills the high responsibility and committed mission that Mexico has entrusted to it. Certainly, the improvement of its facilities and equipment would result in the quality of the training and in the task of raising its approaches to excellence.

With a scalpel in my hand, I dreamed of the work I could do in my professional life, at that moment when I was about to intervene for the first time on a pictorial fragment of the nation's cultural heritage. Now, having the Directorate in my charge, I hope that the School can receive all capable applicants, that its facilities are its own, dignified and spacious, that this institution solve the need that Mexico has for highly trained restaurateurs and museum designers.

Source: Mexico in Time No. 4 December 1994-January 1995