The combination of an academic style and indigenous interpretation resulted in unusual nuances of unique harmony and color within the Baroque.

Very close to the capital of Tlaxcala, in the center of the state, there are at least a dozen baroque temples worthy of admiration and study. Most of them are located next to the highways that connect the capitals of Tlaxcala and Puebla, they are easily accessible to visitors, and yet they remain ignored. Travelers who pass through the region and who show interest in Tlaxcala colonial architecture rarely hear of temples other than the Sanctuary of Ocotlán and the former Convent of San Francisco, architectural wonders without a doubt, but not the only ones.

A tour of twelve of these churches (Santuario de Ocotlán, San Bernardino Contla, San Dionisio Yauhquemehcan, Santa María Magdalena Tlatelulco. San Luis Teolocholco, San Nicolás Panotla, Santa Inés Zacatelco, San Antonio Acuamanala, Santo toribio Xicohtzinco, Santa María Atlihuetzia, Santa Cruz Tlaxcala and the Parroquia Palafoxiana de Tepeyanco) in the company of my friends from tourism in the state, will give us a broad vision of the different stylistic elements of the architectural complex. It should be noted that there are other baroque temples in the state and that the baroque style extends to buildings that are now civil or to chapels that were part of the pulque, livestock or benefit estates that developed in Tlaxcala.

The Puebla-Tlaxcala region had great economic, political and religious importance during the 17th and 18th centuries. This splendor led to considerable construction activity that to date can be seen not only in its capitals, but also in Puebla cities such as Cholula and Atlixco.

The baroque, as a style assumed by the Catholic hierarchy for the representation of its multiple images, found in New Spain a vigorous impulse, fueled by the creative and abundant indigenous labor force. In America, the baroque acquired unexpected nuances, the product of a syncretism between Spanish culture, indigenous roots, and African influences. In Mexico, and particularly in the Puebla-Tlaxcala region, the Indian's footprint was reflected in the temples even after two centuries of colonization. Perhaps the most characteristic example is the church of Santa María Tonantzintla, south of Cholula, with its polychrome plasterwork that competes in profusion of elements with the golden foliage of the Capilla del Rosario in Puebla.

In Tlaxcala the indigenous people did not want to be left behind and they also carved their polychrome vaults in the Camarín de la Virgen, in Ocotlán, the baptistery of the temple of San Bernardino Contla, and the sacristy of the temple of San Antonio Acuamanala, among other spaces. The combination of an official and academic style promoted by the Creoles, and a popular and spontaneous one executed by indigenous or mestizos, will be the characteristic that prints unusual nuances, sometimes contradictory but of curious harmony, to the Tlaxcala baroque temples.

Describing even briefly the twelve temples that we visit would require a lot of space and would force us to restrict the narration, so we believe it is more appropriate to talk about the convergences and divergences of the complex, so that the reader has a general idea of the architectural spaces. useful when you decide to appreciate them with your own eyes. With the exception of one of the twelve temples, Tepeyanco, all the others have the orientation of their transept to the east, the direction of Jerusalem, where the Redeemer was crucified. Consequently, its facades face the west. This feature makes the afternoon the best time to photograph them.

There is a very interesting feature with a profound plastic impact on the facades of some of these temples: the use of mortar, made with lime and sand and applied to a masonry core. Together with the Sanctuary of Ocotlán, the temples of San Nicolás Panotla and Santa María Atlihuetzia share this technique. The technique comes from Andalusian architecture and has its origin in Arab countries.

The contrast of styles in the facades is evident, combining baroque elements with austere and plateresque façades. The changes experienced in the different construction stages are notorious, and there are even towers that were not finished, such as the one in Tepeyanco. In this sense, the facade of the Sanctuary of Ocotlán outperforms the others due to the complete unity of all its elements.

The facade of Santa Inés Zacatelco, seen from afar, gives a feeling of austerity, but looking at it closely, it shows rich ornamentation in its quarry reliefs. Some elements, such as the masks that vomit fruit (a sign of abundance and gluttony) or the faces from whose mouths emerge innumerable volutes that are integrated into the surrounding foliage, evoke details of the Chapel of Rosario and Santa María Tonantzintla in Puebla.

The interior of the temples also brings a set of surprises. As in the facades, we find stylistic contrasts; however, there are several temples that can boast of architectural unity thanks to the fact that they were not built in different stages. Ocotlán is one of them, as is Santa María Magdalena Tlatelulco and San Dionisio Yauhquemehcan, whose interior decoration responds more closely to the Baroque style.

The contrast of styles does not mean that the temples lack beauty or harmony. In some, the Baroque and Neoclassical successfully converge, even giving the latter a visual respite to the rooms. In San Bernardino Contla both styles are combined, covering all the spaces of the vaults, drums, pendentives, and walls. This church has the uncommon characteristic of having two domes in its nave, which gives the enclosure great showiness and luminosity.

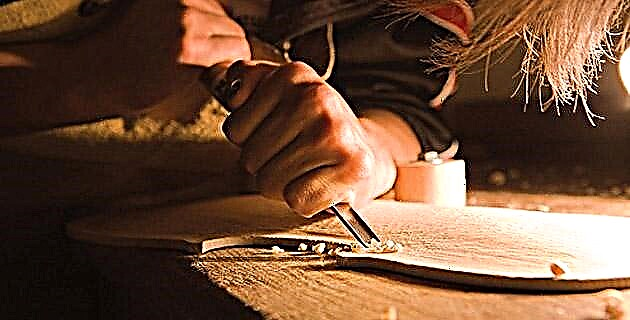

The altarpieces, on the other hand, represent the highest expression of architectural and sculptural baroqueism, with their profusion of scrolls, borders, clusters and faces that seem to emerge like flower buds that open in the middle of the forest. It is impossible to make a description in such a short space of the pillars, pilasters, niches, niches, foliage, saints, virgins, angels, cherubs, shells, medallions, high reliefs, bas-reliefs, sculptures of Christ and multiple other details that fill these wooden masses covered with gold foil.

There are many other details that are worth mentioning in the Tlaxcala baroque temples. Among them the two confessionals of San Luis Teolocholco, authentic masterpieces of cabinetmaking, as well as its baptismal font carved in quarry and with the curious figure of an Indian as a base. The pulpit of San Antonio Acuamanala, also made of quarry, has some faces carved, clusters of vine and other ornate elements that immediately attract attention. The Baroque organs, located in the choir, impose their powerful tubular presence from above. At least two are in good condition (those of Ocotlán and Zacatelco) patiently waiting for the virtuous hands that guide the path of the winds towards celestial harmony.

I end this description aware that it is just a comment on this architectural wealth; just an invitation to the reader to undertake the journey to those corners of great artistic and symbolic value, many of them hardly known by those who decide to explore new crossroads.