It is the early morning of October 29, 1974 in the city of Mérida, the pillory began a painful task, crews of workers attacked the limestone and defenseless walls of the renowned Olympus.

In recent days, events had taken place at a dizzying pace and the balance was dire. The Secretariat for Coordinated Public Health Services, on November 7 of the same year, had requested an opinion on the structural state of the building. The controversial result was unfavorable, which caused the aforementioned Secretariat to close down the establishments that still housed the building. The administration of Mayor Cevallos Gutiérrez dealt the fateful final blow.

Behind each blow of clay, after each removal of rubble, solid vestiges of carved stone emerged, witnesses of a long construction evolution, whose harmonious stylistic connection evidenced the respectful attitude of the designers of yesteryear, whose undeniable concern for the harmony of the environment, In this moment of darkness, we forget.

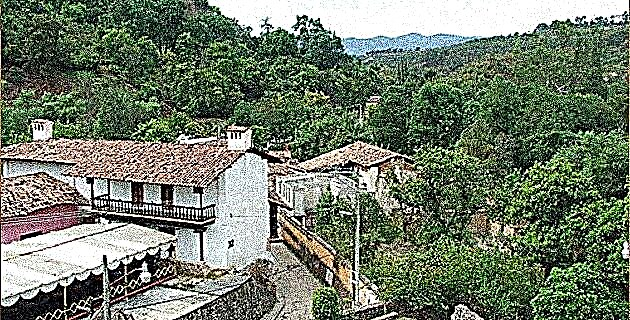

The building commonly known as El Olimpo occupied an area of 2,227 m2, with a constructed area of 4,473 m2, in the north corner of the western face of the central square, a square that until before this attack, conserved all the buildings that it circled.

At the dawn of the 18th century, to the west of the main square of Mérida,… ”there remained the remains of one of the great Mayan hills of which the inhabitants had taken advantage of for construction. When its size had decreased, houses began to be built on that side of the plaza… ”(Miller, 1983). It is probable that the first owner of the property, Don Francisco Ávila, built a building similar in its typology to those that surrounded the square at that time, of a single level, simple, with stuccoed finishes, tall doors of rough carpentry and that over the years, during the possession of the property by its descendants, the building has evolved to become a two-level large house, in which the ground floor served as a warehouse for the products of the owners' farm and occasionally as commerce and, the upper floor as the rooms. It is presumed that on the ground floor, to the east, it would have seven doors that led to a bay and immediately to a corridor until reaching the central patio.

Towards the end of the 18th century (1783), the bailiff of Mérida Don José Cano took the initiative to build portals in front of his house. The city council, when granting the license, authorized to extend the permit to all the inhabitants of the zócalo. By 1792 the property in question had already adopted its first nickname "Jesuit house", probably due to the fact that Don Pedro Faustino, former owner, was very close to the members of this order.

At this time, the façade offered towards the square, on each level, its beautiful portals composed of 13 semicircular arches supported by their respective columns carved in quarry of Tuscan invoice; An axial axis was indicated to this façade as a bell tower formed by a small ogee arch was located on the top or trestle, from which pinnacles were placed at regular distances, coinciding with the axes of the columns, on both sides; Railings of metal bars with wooden handrails were located in the intercolumniations of the upper arch. It is probable that the north facade was only modified by the arcade that was annexed to the east.

Several owners succeeded one another without the property undergoing significant alteration, favorably resisting the onslaught of neoclassicism as the architectural cover of republican ideals. However, at the dawn of the 20th century, under the auspices of the henequen growing bonanza, the entire city was shocked with the consequences of the economic rebound.

In 1883, Mrs. Eloísa Fuentes de Romero, at that time sub-owner of the property, undertook steps to remodel the portals and began work with the demolition of the roof of the upper arcade, likewise the mezzanine that until that moment was demolished boasted outside plump and roof.

On the ground floor, the Tuscan quarry columns were clad, giving them the appearance of pillars and on the upper floor the columns of the outer arcade and those of the inner courtyard were replaced by others of the Corinthian order; the construction system of the roofs in these areas incorporates metallic elements as it uses Belgian beams complemented with wooden joists.

Until that moment, the spatial structure of the building was practically preserved, although the result of the façade modifications produced a neoclassical balance, in which the aspect of the north facing is related with difficulty to the eastern façade. This, in its lower arch, has fourteen edged pillars, each with a colonnade in front, which maintains the 13 semicircular arches of the first design; With the exception of the moldings, colonnades and pillars, this level was lined with partitions. On the upper floor, the code varies although a similar composition is used, with 14 Corinthian columns resting on their respective bases and between them, railings made up of balusters; these columns supported a false entablature, decorated with stucco cornices; the top of the building was made up of a parapet based on balustrades, which featured in the middle part a flagpole in the form of a pedestal also decorated in stucco, flanked by two buttresses towards the ends coinciding with the axis of the penultimate intercolumnium.

The north façade increases its number of doors and goes from six to eight, the two that make the difference are attached to both sides of the hall that it originally had; With this set a cover is designed based on colonnades that reflect the codes used to the east. On the upper floor, the number of windows is maintained and they are complemented by balconies based on balustrades, jambs and lintels are simulated with stucco; the finish in this section only has a buttress on the front of the hall of the same invoice as its similar ones on the east façade.

Later, around 1900, the use of the building became eminently commercial, it is at this time that the El Olimpo restaurant emerged, which gave the nickname to the popular building and with which it is given mine to this day. Street vendors and semi-fixed stalls were installed in the corridors and by 1911, the former governor Manuel Cirerol Canto being its owner, the upper floor was occupied with the facilities of the Centro Español de Mérida. In order to optimize areas, the exterior bays on the upper floor and the bays in the central patio are closed.

The last substantial modification of the property was carried out around 1919 when the owners of properties located on the corner were forced to carry out chamfers, in order to favor the visibility of the carriages and the transit-of the "villain of current urbanism", the automobile, which by then was incipiently increasing in number. As a result of this measure, El Olimpo suffered the loss of the last arch to the north of its main facade, modifying the one on Calle 61, which finally remained in a diagonal position, the adjustment caused the residual space of the eastern facade to be “completed ”With a modulation of four colonnades, on a blind wall on the ground floor and with pointed arches on the upper floor.

Faced with the apathy of its successive owners, starting in the 1920s, El Olimpo entered a phase of gradual deterioration until 1974. The general consensus did not share the devious disposition of its demolition, because although the deterioration was indeed serious, it was feasible to be restored. With the loss of El Olimpo, the community of the city of Mérida managed to wake up from lethargy, magnificent examples of civil architecture had already been lost, but these actions had been underestimated. With the aggression of the demolition of El Olimpo, the offensive was directed towards the central nucleus of the city, towards its central square, the spatial origin of the town, historical origin, beginning of memory and also a fundamental symbol of the settlement.

The Central Square of Mérida stands out, among others, for the great beauty and representativeness of its architectural connections. With the absence of El Olimpo we not only lost unity, harmony and spatial structure, but also what some call temporal memory, historical stratification, the fourth dimension; it is definitely not the same square anymore, it has lost a part of its history.

Currently, the authorities promote the construction of a building to replace the long-awaited Olympus. Various opinions have been heard about what the new building should or should not be. Something above all is evident, if ever the area in which the multi-evoked property was located was occupied by a new building, this will be a reflection of the attitude that as a community we have towards our architectural heritage, as well as at the time, the Demolition demonstrated the prevailing apathy towards our cultural heritage.

Source: Mexico in Time No. 17 March-April 1997